What are the electoral consequences of net censorship?

To sum it up – next to none, at least in terms of sitting ALP members that would be at a decent risk of losing their seats. There will quite possibly be a number of very close contests where, say, 500 people changing their two party vote over net censorship (out of an electorate of 90,000 odd enrolled voters) would make the difference – but those sorts of line ball results in ultra marginal seats, particularly when the sitting member is likely to be a Coalition representative anyway, often come down to literally dozens of individual issues with the most influential usually being old fashion luck.

There are two seats however that could, possibly, perhaps – maybe, on a strange day where dogs and cats start living together in harmony – become an issue.

First up, if we measure the proportion of the voting population in each electorate that is between 18-34 years olds using the electoral roll data, we find the average proportion of all 150 electorates is around 27%.

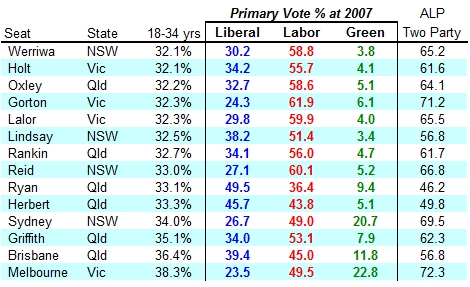

If we now just look at those electorates with a relatively high proportion of 18-34 year olds, let say 32% or more (ignoring the Territory seats), and see how their voting metrics played out in the 2007 election we get:

The redistributions have pushed a few of those seats around a bit, but it doesnt make a great deal of difference to what we’re looking at here. Before we get into that though, a few things probably need to be cleared up.

Firstly, any new party – say the Pirate Party- that runs in the Reps on an anti-censorship platform will be lucky to get their deposit back in most seats. Even in those seats where they do get 4% or 5% of the vote, it would be unlikely that such a party could control the preference flows of its voters anyway – meaning the electoral impact would be minimal, even in those contests where Pirate Party preferences could decide the seat.

Secondly, generic partisan identification and anti-party identification will matter with preference flows.

Let’s say you had 100 voters that would vote for a dedicated anti-censorship minor party – including 40 people that ordinarily vote for Labor at any given election. When it comes down to a two party race between Liberal and Labor – as nearly every metropolitan seat does, those 40 ordinarily Labor voters would then have a decision to make.

They could either pursue a weak form protest and give their primary to a new party but their preferences to Labor over Liberal, or they could pursue a strong form protest by not only giving their primary vote to a new party, but also give their preferences to the party they usually see as their political opposition – the Liberals.

What will inevitably happen is that there will be both strong form and weak form protests – because of generic partisan identification issues – so preferences won’t flow from any protest party into the two party preferred of a Liberal Party candidate at any real level of strength, reducing the ultimate electoral power of that protest.

The anti-generic party identification, while also being an issue in the weak vs strong form protest, also becomes an issue for the third party in the best position to ride the protest vehicle in key seats – the Greens.

Some people will not vote Green under any circumstances, which limits the Greens ability to fully maximise their vote by attempting to position themselves as the anti-censorship political vehicle in key seats.

So even if the Greens could ride enough of the protest vote to come second behind the ALP in a seat, there is a significantly large anti-Green identification among Liberal Party voters that would be expected to push the Labor party, ultimately, over the two party preferred line in any ALP vs. Green TPP contest.

If we look at that table again and focus on the seats with the largest proportion of enrolled 18-34 year olds, we can eliminate Griffith for starters since it’s not only Rudd’s seats, but there is no large Green vote.

So that leaves the three central city seats of Sydney, Brisbane and Melbourne as outside potentials. While the Green vote in Brisbane is the smallest of the three, Andrew Bartlett is standing for the Greens in that seat at the next election, where he will substantially lift the Greens vote anyway, making it more closely resemble Sydney and Melbourne in terms of voting patterns.

To be properly in the game with those seats, the Greens would need to poll nearly 40% on their primary vote. That would require them to reduce the ALP primary down to 40% and the Liberals into the high teens.

Yet that still wouldn’t guarantee them a win, because they’d still be forced to rely on a substantial flow of preferences from the remaining Liberal Party vote, which at this point would consist almost entirely of rusted on conservatives and ideological libertarians (these being ultra inner metro seats)

Would a majority of the rusted on Liberal party voters preference the Greens over the ALP? Some might just to stick it to the ALP – but 60%? Not likely considering the nature of the Liberal Party voters at that stage delivering preferences.

Melbourne would probably be the most likely seat for a Green win – but then only possibly, perhaps, maybe, on a very strange day where the stars align and dogs and cats start living together in harmony.

Ultimately, to be sure, the Greens would need to beat Labor on the primary vote – but net censorship in a million years wouldn’t deliver that sized swing since it’s a third or fourth order issue for most people.

But Lindsay Tanner in Melbourne and Tanya Plibersek in Sydney will still be a little nervous and sniffing the breeze of their local electorate just in case.

The only electoral consequences will likely be in the Senate – in the battle for the final seat or two in each state where 3% of the population make all the difference and where partisan identification is much, much weaker.

UPDATE:

In Melbourne prefs flowed at a high rate in 2007 from Libs to the Greens. Some will argue it can happen again – it could, a really valid argument.

However, it wont flow at the same rate if the Libs vote starts dropping because a larger proportion of Lib primary voters left will have an anti-Green identification – a sort of “those Libs with any Green get up and go, got up and left” effect. Would the reduction in the Lib vote create a small enough reduction in prefs flow to the Greens to let them get over the line against the ALP off a much smaller primary vote- say 32-34%?

I don’t think it would – but many others, validly, will argue it could.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.