Coined by a journalist, the term “churnalism” hints at the daily grind of the newsroom (also known as the “sausage factory”) and presents a rather bleak future for the news media. It is interesting to note that the public relations industry has its own term for this kind of reporting: ROI journalism — Return on Investment journalism.

It’s a strategy that acknowledges the pressures journalists are facing and in so doing, has led PRs to change the way it delivers its product by making it more comprehensive and attractive to the media , ensuring a return on the time and resources both parties have invested. This way the journalist (and editor) get the story, and the PR secures the client the media attention for which it was angling.

Tactics include providing direct quotes and appointed “topic experts” on the issue for time-pressed journalists who may be unable to do the interviews or seek theor own sources. The truth is that public relations professionals have used the current economic climate to their advantage and are tailoring information to suit journalists’ needs so that clients gain the most coverage possible — and journalists are lapping it up.

While print journalists are wringing their hands at the “death of the newspaper”, PRs such as Tom Buchan from Buchan Consulting still view the print medium as important to their work because newspapers “are the opinion shapers”.

Buchan executive director Tom Buchan has observed two trends over the past five years. The first is the accelerated flow of information for senders (PRs) and receivers (the print media), which coincides with an increase in outsourcing to public relations companies. The result is that the print media has an increased dependence on the “intermediaries”, the PRs.

“These two trends are working in concert,” Buchan said.

When asked what strategies are employed to make sure his stories are run, given that there are less journalists around to write them, Buchan said:

“We find we have to do the checking and researching of information that traditionally was done by the print journalists … to verify that what they receive is accurate and truthful. The media is relying on what I call intermediaries to be almost topic experts. In the past, journalists had their own contacts and were able to follow up with three or four other people, now they’re relying on our service.”

It seems that some journalists are allowing PR to do their job for them, relying on spin doctors to check facts on their behalf. According to Buchan, the press release, while still useful for events such as stock market announcements, cannot contain the detail level required by journalists — allowing PRs to cross the line into traditional journalists’ territory and provide tailored information.

“Increasingly we provide a ‘backgrounder’ to provide the journo with background info on any topic of the client we represent,” Buchan said. “So we’ve ticked the newsworthiness box, done the research, and provided contact details of relevant experts.”

From a PR strategic point of view, going the “extra mile” ensures that the topic is easily accessible to a journo who doesn’t know anything about the industry or sector he’s writing about. “It depends on time constraints — sometimes info is run almost verbatim, depending on the checking on our side,” Buchan said.

If this is true, PRs have graduated from the role of intermediary, to becoming sources in their own right. But can a journalist know whether the material provided has been “checked” properly by someone who has a vested commercial interest in that information?

Buchan assures that the reliability of information distributed by PRs is based upon the reputation of the company in question.

“It’s a matter of trust and a matter of our credibility,” he told the ACIJ.

But according to the man The Australian calls the master of spin, Mike Smith, it’s not the job of the PR to be balanced or neutral — that is the responsibility of the media. A former editor of The Age from 1989 until 1992, Smith now runs his own media relations company, Inside Public Relations, which specialises in crisis management. “My job is to put forward my client’s side of the story — my job is not to be fair,” he said.

“My job is to advocate for the client, and as long as that is understood clearly by me and the journalist I can have a pretty healthy relationship and a very ethical relationship with the journalist.”

A key strategy identified by Tom Buchan is positioning the client according to newsworthy “megatrends” so that the story pitched to journalists is consistent with the current news agenda. The global financial crisis is one of these megatrends.

“The GFC is an example for providing a context in which a story lives. We see that as a background setting if you like, of a story. At a time when media was obsessing on what that [the GFC] meant for Australia, it provided a context in which information could be presented,” Buchan said.

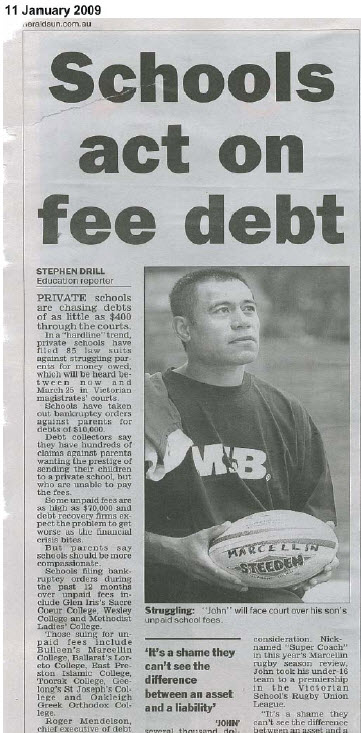

One of Buchan’s GFC-themed stories generated 150 separate articles in a five-week period. Prushka, the firm’s client, is a debt collection agency representing several private schools suing parents for unpaid school fees. A trend, Buchan told the news media, that had risen by 25% with the onset of the financial crisis. The story was pitched as an “insight into a structural manifestation of the crisis” which helped position the client as “part economic commentator and part advocate for the rights of parents and schools”:

The coverage of this issue was very similar, the same sources being recycled by different media outlets. These included spokespeople from the Association of Independent Schools in NSW and Victoria, as well, the headmasters of the schools concerned — Prushka’s clients.

Prushka’s spokesperson Roger Mendelson — who appeared in every single story the ACIJ found on the issue — told the ACIJ that the story “had a life of its own”. Mendelson spoke to hundreds of journalists over this period in early 2009, but he maintains that all the while he was “uncomfortable” with the ubiquitous style of coverage.

“This one honestly took on a life of its own, I used to groan when I was contacted by another journalist … it wasn’t all that good for us — it made us look like the mean guys. I thought the media was being a bit sensationalised on this,” he said.

“I really made it clear I didn’t see it as big a story as they thought it was … but they kept coming back.”

Mendelson said that he was surprised by the herd mentality of the print and online media who pounced on the story after it first appeared in the SMH.

“I even noticed some of my quotes were lifted from elsewhere in certain articles … I didn’t speak to all the journalists who quote me in their stories,” said Mendelson.

Matt Read, the PR in charge of the Prushka campaign at Buchan, views his role less as a spin doctor and more as a “broker of information”.

“[The information] was sent selectively to chosen journalists. If it’s a good enough story, I’ve found in these situations it takes one credible reporter and then other journalists pick up that story,” he said. “It was certainly initiated by us … but it was also helped by the context of what was going on in the economy and education, so we were contributing to an ongoing debate.”

Another example from the Buchan company tackled the “water issue”. The Australian ran an article celebrating Buchan’s client Rubicon, an irrigation consultancy. Buchan pitched the story based on the “critical need” for sustainable irrigation practices here and across the globe, as well as the need for “good news water stories” which were hard to find at the time when stories about water scarcity, drought and the plight of the Murray-Darling abounded.

The published version of this PR story features just one voice, that of Rubicon Australia CEO and founder David Aughton, and he comes out looking pretty good in this perky, promotional piece, headed “Rubicon Systems founder walking on water: Can this man solve the globe’s water problems?”

According to communications coach and public relations consultant Bob Hughes, who represents the Advantage Job Index formerly known as Olivier Recruitment Group’s Internet Job Index, the credibility of the PR company in question is paramount. The index surveys positions vacant ads on average each week on commercial job websites, and along with the rival ANZ Job Index, the statistics generated are used by analysts to predict where the job market is heading.

It’s a favourite with the news media and, according to Hughes, the index is in the AAP diary so it’s guaranteed coverage every month. Hughes said that creating a sense of confidence in a product is achieved by getting viewers and readers to associate the index with its professional director Robert Olivier, who makes scheduled television news appearances every month on the eve of the index’s release. As a former journalist, Hughes said garnering coverage of the index has relied a lot on his own profile and reputation.

“I was a journalist for 20 years … so I have a pretty good news sense and I’m the one who’s looking for the story in the figures and what the experience with the market is for the month … all you can do is rely on experience and try and deliver something that is of interest to people.”

Hughes also puts the releases online and publicises them via his personal page and Twitter, before they are sent to media outlets. Old contacts also come in handy at release time. Hughes makes sure to target senior finance and economic journalists personally to make sure they carry the story.

“How many emails would Peter Martin (The Age’s economics correspondent) get every day, there would be hundreds, so it’s very easy to miss what we have. So I’m always looking for a good story for them.”

If you think that former journalists crossing over to public relations is tantamount to “selling out”, think again. According to former Fairfax journalist Mike Smith, it makes you much more credible and even ethical. Smith says that the best PRs have a background in journalism, particularly those in the fields of community relations, strategic and corporate PR.

“I have no problem with the word spin, it does not mean misleading or lying — it’s putting inflection on a set of facts to give them power,” he said.

Although not all spin is equal. Smith claims the most “evil” spin is political.

“I get really scared by some individuals brought up in political PR. They’re plucked out of electoral offices at a very young age, brought up on one side of politics. They’re either with you or against you, part of the brotherhood. They not only ‘spin’ things one way, they are actually blind to the other set of facts … A lot of political PR is lying.”

This disdain for the blind advocacy of political PRs comes from the former newsman and member of the Australian Press Council who nowadays manages the public profiles of clients such as entertainer and businessman Steve Vizard, and former Governor-General Peter Hollingworth, whose appointment was dogged by allegations he failed to act appropriately over a series of s-x abuse claims while Archbishop of Brisbane in the 1990s. In this context, Smith maintains that spin is “the journalist’s advice [to a client] … to give out more information rather than less.”

While massaging the truth for commercial gain is not traditionally the journalist’s work, Smith points out the similarities between journalism and PR.

“When I say spin I mean journalists use spin — you see it in every news room every day, editors saying to journalists ‘what’s the angle, what’s the spin’?,” he said.

But there is one, fundamental difference between public relations people and journalists:

“Public relations people are outnumbering journalists. The trend is going in the wrong direction — in PRs’ favour , but ultimately, editors and journalists have the final say on what is and isn’t published. That’s a huge advantage, one that should outweigh the numbers advantage PR has over them at the moment.”

*Sasha Pavey is a freelance journalist based at the Australian Centre for Independent Journalism.

**Extra research by Biwa Kwan, a journalism student at the University of Technology, Sydney.

very good analysis – and example case.

I remember reading the original article – and thought it was a media beat-up, but the SMH was just printing what they had been given.

There’s a world of difference between ‘spin’ and ‘angle’, and I find it very hard to believe that editors at newspapers are using the former, in spite of Smith’s claim. A story needs an angle, a focus.

If you continually spin bullshit, it doesn’t take long to wear out your welcome.