They would, wouldn’t they? At Rio Tinto they just could not wait to give their four employees the sack. As soon as the Chinese court delivered the sentences, the captains of industry in London gave their stamp of approval to the justice system of the totalitarians. What depths company directors will sink to in complying with the market edict that they must do what is in the best interest of the company. Work for this lot at your own peril.

Not that Rio’s actions are just about letting their former iron ore negotiating team carry the complete can. There are the next round of negotiations on an iron ore price to get on with but more importantly the need to ensure that the buck does actually stop with those now in the Shanghai slammer.

The London Daily Telegraph spells out another danger.

“It is understood that the SFO has already started gathering intelligence about the activities of Rio,” the paper reports, “although a spokesman for the SFO stressed it had not yet launched a formal investigation. The US Department of Justice could also examine whether there is a case to answer. The report continued:

A spokesman for Rio said: “We will always co-operate with any official government investigation but we would not comment on whether we have received an approach from such authorities.”

Rio has fired all four employees, and said that they had engaged in “deplorable behaviour”.

It insists that the four acted “wholly outside” its systems, but the company could face further problems if more information emerges over the charge of stealing commercial secrets.

The Chinese court declared that Rio had used inside information to cause the collapse of an annual round of price negotiations over the state’s iron ore contract with the cartel of big mining companies: Rio, BHP Billiton and Vale.

Rio said on Monday that it could not comment on the charges of obtaining commercial secrets because it had “not had the opportunity to consider the evidence”.

It’s worth noting those words “not had the opportunity to consider the evidence”. In the company’s view they apply when it is a question of the guilt or innocence of senior management but not when considering the fate of the underling Stern Hu. What a cowardly lot.

An Australian investigation. Australia’s Foreign Minister Stephen Smith is doing his best not to upset the Chinese government by being too critical of its judicial system while pretending to have a concern for the fate of the Australian citizen who has fallen victim to it. Perhaps the best way for Smith to prove that he is not just another sycophantic hypocrite is to request the Chinese to allow Stern Hu to be interviewed by Australian Federal Police as part of an investigation into whether Australia should be launching proceedings against further Rio Tinto officials under the Criminal Code Amendment (Bribery of Foreign Public Officials) Act 1999.

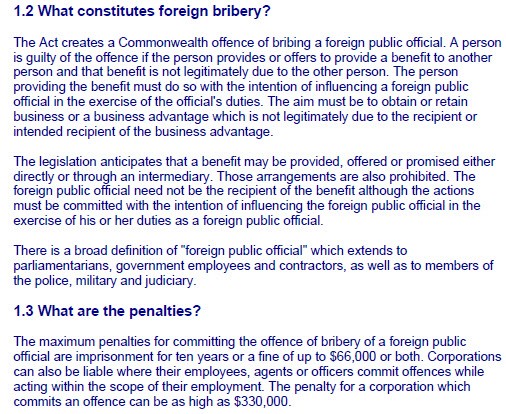

Transparency International summarises that law in this fashion:

The most significant implications for Australian businesses arise from the inclusion of the offence of bribery of a foreign public official in the Commonwealth Criminal Code. The Code has far reaching principles relating to corporate criminal responsibility. The Code extends the usual common law principles by allowing the prosecution to lead evidence that the company’s unwritten rules tacitly authorise non-compliance or fail to create a culture of compliance.

It captures situations where, despite formal documents appearing to require compliance with laws prohibiting foreign bribery, the reality is that non-compliance is expected. Compliance on “paper” is not sufficient: there must be an environment of compliance operating within the company.

A company can be criminally liable if the corporate culture:

- directs;

- encourages;

- tolerates; or

- leads to

non-compliance with the criminal provisions proscribing the bribery of foreign public officials.

In addition, under the Australian law, a company can be criminally liable if the company fails to create and maintain a corporate culture that requires compliance with the law. Under the Australian law, corporate culture is defined to mean: an attitude, policy, rule, course of conduct or practice existing within the body corporate generally or in the part of the body corporate in which the relevant activities take place. The new provisions relating to corporate culture significantly extend the scope for corporate criminal responsibility beyond the current position at common law. In fulfilment of fiduciary and statutory duties, directors and senior managers of companies are recommended to ensure that appropriate and effective compliance programs are in place.

Think pink. I am being taken to task by some associates (and one of them at least must be obeyed) for not acknowledging the great work that Tony Abbott performs in supporting the fund-raising cause of breast cancer research. It might be lycra, I’m told, but at least it’s pink lycra and the McGrath Foundation is the beneficiary. I promise to remember that as the Opposition leader pedals from Melbourne to Sydney.

Quote of the week.

“The government’s core economic principle of conservative countercyclical policy interventions is standing the test of the gyrations of the economic cycle.” Kevin Rudd, 29 March 2010

No shock, no horror, no probe, no bid. Surely the pick of the year’s non-questions asked in Federal Parliament:

QUESTION TAKEN ON NOTICE

ADDITIONAL ESTIMATES HEARING: 9 FEBRUARY 2010

IMMIGRATION AND CITIZENSHIP PORTFOLIO

(98) Program 4.3: Offshore Asylum Seeker Management

Senator Humphries asked:

(1) Is there a ballet teacher at the Christmas Island IDC?

(2) How much did it cost to fly the dance teacher over to Christmas Island and be paid to teach dance classes?

(3) How many classes do they teach per week?

Answer:

(1) No, there is no ballet teacher at the Christmas Island IDC.

(2) No dance teacher has been flown to Christmas Island or paid to conduct dance lessons for clients by the Department.

(3) Not applicable.

Um, Glen, sorry to be a nit-picker, but the Bribery of Foreign Public Officials Act 1999 may not actually have any relevance here.

It appears that the one supposedly bribed was Stern Hu himself, who is not a public official as described under the act.

Hu was convicted by the Chinese of receiving bribes to provide a lower price on Rio product to selected smaller Chinese steel mills (undercutting the price those mills would have had to pay the larger mills for product that the larger mills would have bought direct from Rio for onselling), not of bribing Chinese Government officials.