Most of the nation’s economic hard heads don’t willingly submit themselves to the Budget media lockup, leading to a mad scramble to interpret thousands of pages of papers alongside the rest of the nation before the newspapers come knocking. Luckily for Crikey, most leave it until the next morning to properly unleash on what the document really means for Australia’s balance sheet, with the clear consensus that the government could have gone further to deliver some serious cuts, rather than relying almost solely on the resources boom to return to surplus.

We asked six of our leading numbers wonks for their considered take on this year’s dour piece of electioneering emanating from deep within the disciplinary wing of Wayne Swan’s super-ego.

Shane Oliver, chief economist, AMP Capital Investors: With major announcements on health, tax and superannuation in recent weeks, it was going to be hard for the Budget to come up with anything really exciting. In the event the Government still managed to come up with plenty for ordinary Australians, in the form of tax simplification, the delivery of another round of income tax cuts, and reduced tax on savings.

The upwards revisions to growth forecasts were pretty much as expected, but perhaps the highlight in the Budget is the projected return to surplus three years ahead of schedule. This, along with the expectation that net debt will peak at just 6% of GDP, provides a stark contrast to the worries about excessive public debt in Greece and other advanced countries. Net public debt in Greece is 95% of GDP, and in the UK it’s 59% of GDP.

A criticism, though, is that the Government appears to be mainly relying on stronger growth and the terms of trade boost to cut the budget deficit. With the economy well and truly on the mend, it could have been more serious about containing spending, which in turn would have helped take pressure off the RBA and interest rates.

Saul Eslake, The Grattan Institute: For a pre-election budget, this was a remarkably restrained exercise. For the four years from 2009-10 through 2012-13, it provided for net “give-aways” totalling just $7.5 billion, compared with four-year totals of $36 billion and $50 billion for the Budgets at the same stage of the two previous electoral cycles (in 2004 and 2007).

The Government has stuck to its commitment to keep real spending growth to less than 2 % per annum, and has more or less delivered on its pledge to direct any windfall revenue gains towards improving the budget bottom line (although that is strictly true only if you extend the period for which this applies out to 2013-14). And those revenue windfalls have turned out to be bigger than expected, allowing the Treasurer to foreshadow a return to surplus three years earlier than previously projected.

Given that the surplus for 2012-13 is only $1 billion, that doesn’t leave much room for additional spending between now and the election, if the Government wants to stick to that timetable, unless revenues are revised up again.

I don’t have much quarrel with the economic forecasts underpinning the budget, with one important exception, that I find it hard to accept that inflation will remain at 2.5% while the economy is, by 2011-12, growing at an above trend-pace of 4% while unemployment has fallen to what Treasury now defines as the “full employment” level of 4.75%.

Overall, however, this is a responsible effort, given where we are in the political cycle.

Alan Oster, chief economist National Australia Bank: From a big picture viewpoint, this Budget is all about bringing the Budget back to balance 3 years earlier than previously expected (2012/13).

The main mechanisms to get there have been largely pre-announced — namely the mining super profits tax, the increased tax on tobacco, cheaper drugs under the PBS and more effective returns from Tax Office compliance. The really big items on the expenditure side have also been largely pre-announced. These include the lowering of the corporate tax rate, an early start on these tax cuts for small business together with aggressive depreciation allowances, a resources exploration fund to support mining exploration and the cost to the Government of increased support of the higher superannuation levy.

The new initiatives include tax simplification for lodging tax returns, additional spending on training and skills, a substantial increase in hospital and health spending and a 50% reduction on tax paid on interest from bank and financial deposits (up to the value of $1000 per annum). The latter is clearly targeted at increasing saving incentives and is welcome. Also, there are useful measures aimed at improving Australia’s financial competitiveness via lower withholding tax, purchases of RMBS (to help that market) and additional investment in Australia as a financial centre.

Looking to the credibility of the Budget reduction framework, much will inevitably be tied up with the mining super profits tax — will it pass the Senate and in what form? The Government is, however, largely linking its passing to the lower corporate tax, better depreciation allowances, and the increased superannuation levy.

Outside these political issues, NAB does not have major problems with the Budget from a macroeconomic viewpoint — with fiscal and monetary policy now more aligned. The spending cap of 2% per annum is tight and implies lower public spending than even we expected. We have indeed marginally lowered our growth forecasts to reflect this. While the Budget figuring depends on the forecasts, we find them credible — indeed we expect stronger growth over the next two years . Also, the Budget implies a significant structural tightening of around 2% from 2010/11 after the very large deficits of the previous and current years.

Of course, much will depend on politics. As well as the issue of the fate of the mining super profits tax, the Budget clearly shows that if we want to return to surplus in the current environment, there is no scope for further aggressive pre-election spending by either party.

Warren Hogan, chief economist ANZ: As far as pre-election Budgets go, this one should be regarded as measured. None of the big spending associated with the 2004 or 2007 Budgets. An early return to surplus and ongoing commitment to contain real expenditures by 2%, which the government has now extended until a surplus of 1% of GDP is achieved.

While there are many small, targeted new policy initiatives within this budget, the Government remains focused on some key strategies issues; most importantly in our view, a commitment to support a higher rate of national savings in the future. Tax relief for savings vehicles such as deposits and bonds will have some impact on raising national savings over the years ahead, and as the Budget improves, the extent of this tax relief can be extended from the modest amounts put forward last night.

But the centrepiece of the Budget is a quicker-than-expected return to surplus, which is now forecast to happen in 2012-13, three years ahead of the schedule set out in the mid-year update last November. All of the improvement in the Budget is due to a better economic outlook, with policy decisions actually working in the other direction.

For example, the move in the 2012-13 budget position from a previous forecast deficit of A$15.9bn to a surplus now of A$1bn comes on the back of a A$19.6bn improvement in the budget due to “parameter variations” (read: changes to the economic forecasts). In the same year, new policy decisions detract A$2.6bn from the budget bottom line.

There are clear risks to the economic outlook that lurk behind this otherwise strong set of core projections. The situation in Europe remains problematic despite recent policy initiatives, and of course, much of this economic strength in the forecasts is underpinned by China sustaining a strong economy for many years. If these international economic risks emerge as likely outcomes, the budget position will be severely affected. Our main concern within the economic forecasts is the almost unbelievably well-behaved inflation outlook.

If this budget is boring, then job well done Treasurer. Boring is good in a environment where many of the wealthiest countries in the world are facing government deficits around or above 10% of GDP. For some countries, tough decisions are imminent.

In Australia, government debt levels will “peak” well below previous estimates at just over 5% of GDP, compared to well over 50% for many countries and close to 100% for Greece. Australia’s financial position is strong, highlighted by the credit rating being affirmed at AAA following the Budget. More could be done, but in an election year, the Government needs to be commended on limiting the waste and remaining focused on some key strategic indicatives.

Craig James, chief economist CommSec: The Government believes that a no-frills, no-nonsense budget is required. We beg to differ. Australia was successful in avoiding recession last year and, unlike other advanced nations, is not weighed down by huge deficits and debits. We should be building on that success. Spending should be cut, not curbed, so that the Reserve Bank — and home-buyers — don’t have to shoulder the burden.

But policy decisions since November last year increase the deficit by $3 billion. The Budget deficit is tipped to improve by over $16 billion next year, but none of the improvement is due to Government efforts. The deficit is expected to improve by over $31 billion in 2011/12 and only $600 million of that is due to Government.

The Henry Tax Review has been handed down, but the Government has only opted for only a handful of the 138 recommendations. But where the Government deserves credit is to show some discipline on spending. (Effectively it’s promised a lot, but nothing happens any time soon.) So we give the Budget a mark of 13/20.

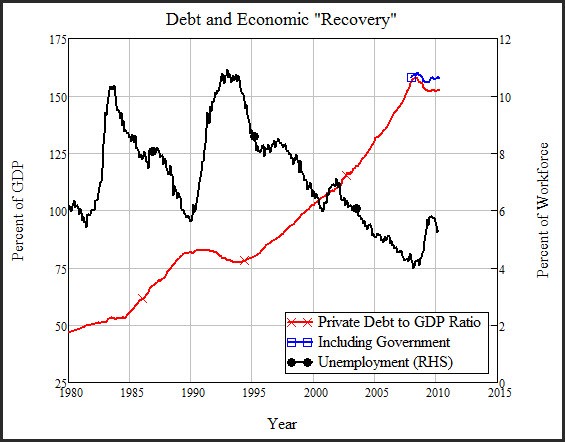

Steve Keen, University of Western Sydney economic dissident: Every recovery from a recession since 1973 has only occurred when private borrowing has taken off once more. The drop in unemployment from over 10% in 1983 to 5.5% in 1990 coincided with private debt growing from 50% to 80% of GDP; the bigger still drop from 11% in 1993 to 4% in early 2008 was accompanied by private debt expanding from 75% to 160% of GDP.

So for Swan’s fiscal dreams come true — the budget returning to surplus by 2012-13, and real economic growth hitting 4 percent next year — either private debt has to grow to even more unprecedented levels, or the 3rd Rudd-Swan has to boldly take us where the Australian economy has never been before (or at least not since 1965): into a recovery that is not built on rising levels of private debt.

Count me as a non-Trekkie on this point: though it would be good if it could be true, I expect that an economic recovery without expanding private debt will prove to be as much a work of fiction as Warp Drives and Transporter Beams. For worse and not for better, we have become a Ponzi economy where demand is debt-driven — even our recovery in 2009 involved halting the slide in private debt, and adding a substantial amount of government debt to it.

I therefore expect that the projection of the budget returning to surplus and so-called fiscal conservatism within 2 years will be as reliable as the 2007 forecasts of most (neoclassical) economists that 2008 would be a great year, and that claims the world would experience a serious financial crisis could comfortably be dismissed.

Fortunately, Swan did hedge his surplus bet with the observation that European turmoil points out that the GFC has not entirely vanished, and deficits may still be necessary here to support aggregate demand. So he does have an out. But just as this year’s final budget was a substantial positive revision to the projections (thanks to an unprecedented government stimulus, Chinese largesse, huge rate cuts, and an artificially stimulated housing market), I expect that next year’s actual budget outcome will be a substantially negative one to tonight’s projections.

That would be a good thing, compared to the current obsession on both sides of the political fence with returning the government accounts to surplus. Forcing austerity on governments when private sector credit is also contracting hits the economy with a double-whammy of negative forces. Though I don’t believe that we can forever government-spend our way out of the GFC, targeting government surpluses now will only exacerbate the downturn that is already becoming apparent in private retail spending.

The Economic Dissident said: ‘we have become a Ponzi economy”.

Would he care to name a real economy that is not a Ponzi Economy – ie does not rely on continued growth in population, production and resource consumption in order to function?

RobynSP, you have no idea who Ponzi was or what he did, do you?

A Ponzi economy is one that relies on the continuing increase in paper value of assets as equity for loans to purchase even more assets. Such, as, say, the US economy circa 2007 when it was perfectly ok for everyone to borrow against the increasing value of their house to continue consumer spending and speculative real estate investment, because even if they defaulted, their debts would be paid for by the increasing value of their house. It has nothing to do with real growth in production or population.

Aren’t these all the same talking heads who got it all completely wrong every year before now?

Has Steve finished his walk yet by the way?

Is there a single reason we have to listen to these wankers as they babble and burble their crap?