With the lead in to our first performance sparking a flurry of prop construction, last minute rehearsals and bouts of food poisoning, time has been scarce, so apologies for the lack of updates. My food poisoning was divinely mandated: I received it from a sampling of holy water at a Thimphu monastery. I thought initially that my vomiting was punishment for my heathen ways, but my host pointed out that it could also be seen as a painful enforced detox of all my previous sicknesses, which is the best a heathen should expect from holy water, I suppose.

In the lead up to our first performance the troupe went on a drama camp to Paro, a town west of Thimphu that boasts Bhutan’s only airport. Nearby our camp was a cave high up in the mountainside- if one squinted one could see the malevolent glint of a TV screen in the cave mouth. This is the infamous Cursed TV of Paro — a family bought it when television was first introduced to Bhutan in 1999, but within months of the purchase half the family members had died. They sold it to another family, who also suffered several sudden and tragic deaths. To stop the cycle the second family left the TV in the mountainside cave. When I tried to take a photo of the TV with a digital camera, the image came out pitch black — a chilling omen which sent the entire theatre crew scurrying into the van and away. Tshering Dorji, one of the founding members of the Happy Valley theatre group, told of a prophecy (possibly generated by his own imagination) of a Yogi who would one day ascend to the cave, and through the powers of his meditation destroy the evil power of the TV — while also getting to catch up on the latest episode of Two and a Half Men.

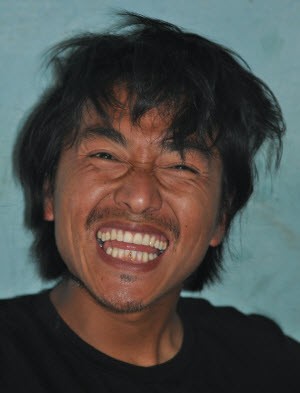

Below is a profile of Tshering which I wrote for the Bhutanese magazine Drukpa. Interspersed in the profile are excerpts from a larger article on Happy Valley by Xochitl Rodriguez, so thanks Xochitl for the excerpts and photographs.

TSHERING DORJI: THE BLOW HORN *

*The Blow Horn or conch is one of the 8 lucky signs of Buddhism, and we incorporated it into our performance for the SAARC conference. The sound of the conch being blown is said to spread Dharma across the earth. Tshering is here referred to as a Blow horn in honour of the social message he has to spread and the loud mouth with which he spreads it.

Tshering Dorji was born in 1981 in the village of Jagarthang just outside of Paro. He graduated from high school but received poor grades — an experience that he feels strengthens the argument for having creative as well as academic career paths available to young people in school:

“That’s why I feel bringing more art and drama into Bhutan would be so useful, to provide a pathway for people like me that are meant for this discipline, rather than a more academic path. It would also be wonderful to convince parents and others that by choosing performance as a profession, their child could contribute to society just as much as if they were a doctor or engineer”.

Tshering had a passion for acting from an early age, but did not pursue the profession immediately upon leaving high school- instead he began work as a tour guide. Working as a tour guide he was able to earn enough money in three months to buy a car. But at the end of a day of quick earnings, fancy dinners and fancy hotels, he would go to bed feeling that this wasn’t what he was born for. But he is thankful to the profession for giving him the financial base to pursue his passion for theatre- and having a car is very useful for dropping off fellow performers — without one it may have been much harder to convince them to stay for late night rehearsals!

In 2005 Tshering took up an opportunity to receive training from visiting Fillipino drama specialists in a workshop program organised by Tshering Gyaltshen- the result of the training program and subsequent performance tour, sponsored by ‘Save the Children’, was ‘The New Theatre Company’. Tshering is grateful to Tshering Gyaltshen for providing this initial spark for street theatre in Bhutan, and continues to admire the new ideas and social messages that Tshering Gyaltshen promotes in both his films and theatre work- the beneficial impact of this work in the lives of youth in Bhutan is an inspiration for Happy Valley’s own activities.

Happy Valley as an idea was conceived when Sangay Rinchin, Sonam Rinzin and Tshering Dorji, who had all done junior high and high school together, met and agreed upon the concept of setting up a youth organization based on a system of fairness and equity. “Our main intention was and continues to be to help others. We wanted to initiate a business with a different purpose,” said SonTshering Dorji. Happy Valley uses a non-profit co-operative approach to tackle social issues by engaging youth and calling upon them to initiate their own participation in society and specifically, social advocacy campaigns.

Tshering’s first cinematic acting role was in the movie Layngon Bum. He had learnt during his time studying drama of the differences between live drama and film, but only came to truly understand this distinction by experiencing it. He has subsequently decided not to pursue a further film career until he writes a film of his own, but is still very grateful for his first onscreen acting experience. As he describes it:

“Life is a field of experience- wealth will go away and friends and family will die but experiences and memory will always remain- until you get dementia at least”.

Tshering lacks the legendary temper of his fellow Parops (inhabitants of Paro –the Paro temper is said to derive from their regular battles with invading Tibetans). This evenness of temperament has assisted greatly in dealing with the daily difficulties of working in a co-operative. In Tshering’s opinion, so many youth groups have fallen apart in Bhutan because of the failure of members to move beyond ego clashes and petty disputes:

“If you argue with another person, don’t hold on to your anger. Next time you see the person, let your mind be blank, and start anew- how else can you expect to be able to work together?”

This pragmatic approach is essential in a co-operative, especially a theatre co-operative, where creative disagreements are a daily occurrence. But if ego is put aside, creative clashes can be a spark for unexpected and exciting ideas rather than personal vendettas. This non judgmental attitude has also been of enormous benefit to fellow Happy Members such as Namgay, or Elvis as he likes to be called (He says Elvis’s example inspored him to take up drugs). “Before I joined, I took drugs and got in gang fights,” says Namgay, “My old friends used to respect me, but as a bhai (an Indian term equivalent to a mafia don). Now people respect me, but as an equal. Despite the difficulties we face, Happy Valley has given me hope, and changed me as a person.”

Tshering had an opportunity for further education, an acting course in Pune, India, early on in Happy Valley’s development, but he made the choice to commit to the group rather than pursue his study options.

Before his training, Tshering had thought he could be the best actor in Bhutan or the world- but once exposed to training, in his words, ‘you realise your cup is so empty- that you can always learn so much more.’ Having started off his career just wanting to act for its own sake, Tshering now realises the profession can also be important for society- live performance can be a uniquely powerful medium to spread social messages.

“I have seen so many workshops, lectures and public moments where people are just sleeping in the audience,” Tshering explains, “But when we do our street theatre performances, the audience might jeer and heckle, but no-one is ever sleeping!:

The novelty of street theatre in Bhutan has led to plenty of difficulties: taken aback by the confidence of the group, audience members have approached the Happy Valley troupe after performances to ask whether they have been drinking. But despite the jeering and misunderstandings, these street theatre shows do offer moments of genuine connection with the audience, and it is in these moments that Tshering gets that surge of fulfilment that his tour guide work never gave him.

He first felt the sensation whilst performing in the first street theatre in Bhutan, at Yangchenphu Higher Secondary School. He felt this feeling again when Happy Valley did their first performance together, a social advocacy show on HIV/AIDS sponsored by the Ministry of Health. He recounts how one of the show’s messages was that the common myth that wearing two condoms is safer than wearing one is not scientifically correct- the friction between the condoms is more likely to break them. People jeered at the risqué subject matter, but the fact that the performance got such a strong reaction was evidence enough that the audience would remember the message. Tshering describes these moments with the fondness and fervour of a performer who recognises both the beauty and power of his craft:

‘When I look at the eyes of the people I can see the ideas that we are trying to give sinking into them. Soon after the show is done I get an immense feeling of satisfaction- it is giving me a sense that I have found the purpose of my life.’

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.