The debate on the RSPT, to date, is not getting to the heart of the matter. For whatever reason, the wrong financial metrics are being used to assess whether “the 40% tax rate is too high” or “the 6% cut-in rate is too low”.

The main distraction is the “effective tax rate” (ETR) figure that mining companies are using to argue against the tax. It is a mistake to compare effective tax rates directly between industries because it does not tell us exactly how profitable the industry is overall, but only what slice of those indeterminate profits are paid as tax. The argument has been made many times that the high risk of mining projects demands a high return — but again, repeatedly pointing to the ETR for projects only tells us the slice paid in tax, not the level of earnings the company can retain to distribute as dividends or invest in other projects.

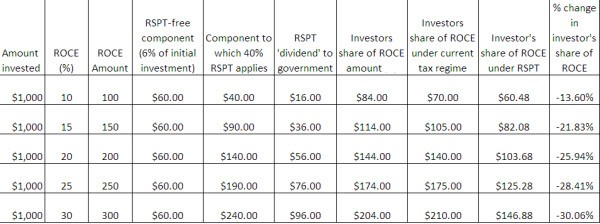

An alternative way to evaluate these questions is to look at profitability of mining projects as Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) — a percentage calculated by dividing the adjusted net profits before interest and tax by the value of the capital employed. A simple model can be built that does not require either a detailed knowledge of mining industry economics nor makes simplifying assumptions that can be challenged by either side of this debate. Put another way, ROCE cuts through the confusion and gets to the crux of the debate — whatever the average effective tax rate is within a sector, it is the average ROCE that shows whether or not super profits are being made.

One factor that has been widely overlooked in the RSPT debate is that the RSPT deducted before interest and tax, is not actually accounted for as a tax, but as a dividend to the government. That means that when corporate tax is finally applied to earnings, the RSPT amount already paid is not taxed again.

Moreover, as is widely known, the corporate tax rate is proposed to be reduced from the current 30 per cent to 28 per cent over two years.

Finally, then, using the ROCE method of assessing the tax leads to the following question (perhaps the most important question in the debate): by how much would a company’s after-tax earnings decrease under the RSPT? That is, how much less is available to distribute as dividends or reinvest in the business?

The calculation produces some surprising results as the table below shows.

It must be noted here that this example does not take account of a company’s gearing position. Miners typically fund their fixed capital costs with equity, and then fund working capital with debt. The more a company borrows, the less will be the amount of ROCE left to distribute to shareholders. This has been clearly shown in the case of Fortescue, which has seen its share price tumble since the RSPT announcement.

On the other hand, the figures above do not take account of accelerated depreciation in mining assets when calculating the corporate tax bill — which, of course, reduces the amount of corporate tax paid.

What the table does show is that the amount money to be distributed as dividends or reinvested, is nowhere near the 40% headline figure used to calculate the RSPT, and shows even more clearly how misleading the effective tax rate of 56.8% being promoted by the mining industry is. That figure is not wrong — but it gives a misleading impression of the true impact of the tax on the return investors make on their money.

*Munif Mohammed is presently GM finance projects for a major retailer in Sydney, and has worked as a CFO and finance professional in government, financial services, IT, FMCG and retailing for 25 years.

Talking of an “effective tax rate” which includes both royalties/dividends (including the RSPT) and regular tax is wrong by definition, because if it were reduced to zero, it would mean that the mining industry was getting their inputs (the minerals) for free. No other industry gets to pay nothing for their raw materials. Royalties and the RSPT are fundamentally not “taxes”, they are input prices.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but does the above table not account for royalties? Difficult to include in a simple and clear way, I know, since it changes the ROCE itself, in a project-specific manner rather than how ROCE gets carved up. But surely it is an important element of the debate?

Could we assume that miners are currently earning at least a minimum 10% ROCE? And then based on the Henry Review’s remarks that royalty revenues are currently approximately $1 in $7 profit (sorry, I don’t remember exactly which measure of profit) royalties are therefore a minimum of $10 (1/7th of $70 after-tax profit in the 10% ROCE line)?

That would mean that in the top line “Investors share of ROCE under current tax regime” should be more like $63, and the “% change in investor’s share of ROCE” would be -4%.

With a ROCE of 30%, the % change becomes -27.6% …

It is good to see Munif Mohammed place these calculations on record; such factual analysis has been sorely missing in this debate so far. And these numbers are before the rebate of the royalties miners currently pay, thereby reducing the overall “tax” cost to them.

Re Jamesh: Even if the RSPT is to be viewed as the input price then a significant increase still changes the economics of mining projects and many will be no longer viable, thus reducing future employment.

Previously published analysis indicates that the break-even point, after allowing for return of royalties, etc, is actually reached at an ROCE of approximately 11%.

Very broadly speaking, this article’s conclusions understate the amount of ROCE available for shareholder returns or retention within the corporation at the lower end (6% return) by about 20%. It is thus apparent that the analysis is fatally flawed through not including industry figures for return of royalties.

Certainly, I am far from convinced that, across the board, the return to investors is reduced throughout the band +6% ROCE upwards.

Further, from Crikey earlier this week we discovered that larger mining corporations have been able to pull astonishing rates of return (profits before tax, to the common person) from their mining operations – 30% is not even attractive to the biggest players, who operate closer to 60% on average.