Good theatre, to incorrectly and embarrassingly quote Andrew Lloyd Webber, heightens each sensation and wakes imagination unlike few other art forms. There’s an intimacy, an immediacy; a perverse, vicarious pleasure in being in the same room as an unfolding drama.

So does that work when you put it up on the big screen?

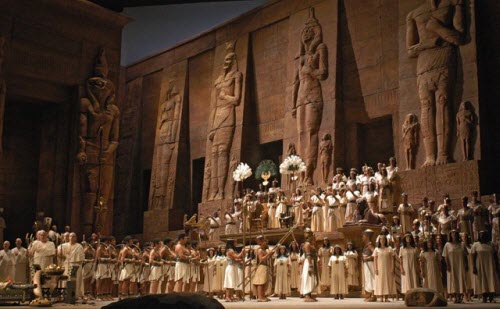

At many cinemas around Australia this weekend, you can see perhaps the grandest opera of them all — Giuseppe Verdi’s epic Aida — in all its high-definition glory. From the world’s most revered company, no less — New York’s Metropolitan Opera. It’s part of a season of performances in arthouse cinemas from The Met in Australia, and indeed around the world. Opera glasses not required; popcorn optional.

Theatre in the multiplex has its advantages: obviously geography (it’s a rare experience for Australians to see a renowned company from New York or London) and economy, certainly (even at $20-odd, the movie ticket is considerably kinder on the credit card than a $100-plus seat at an opera house). And as theatre companies globally struggle to keep the stage above water, it’s seen as an important new revenue stream; as Vanity Fair reported earlier this year, not only are the movie tickets themselves a money-earner for the debt-ridden Met, it also helps drive subscriptions:

This season, more than 1,000 movie theaters in 44 countries will screen live performances from the Met. With about two million people expected to watch one or more Met operas on the big screen this season, [Met manager Peter] Gelb’s new initiative is as close to populism as opera can get. For $20 a ticket, more or less, the greatest operas in the world are now accessible to everyone, from Mobile, Alabama, to Topeka, Kansas, from Osaka, Japan, to Lima, Peru. Some of these viewers have never seen an opera. Who can foretell what kind of impact the Met’s high-definition broadcasts will have?

Opera-lovers of an earlier generation learned to appreciate the art form by listening to the Met’s live public-radio broadcasts on Saturday afternoons. One day some of the people watching Turandot in movie theaters might be subscribers to the Met — or, better yet, donors. “We’ve had thousands of new donors through our high-definition transmissions,” Gelb told me. “Did I mention that to you? That’s where the future million-dollar donors are going to come from.” In other words, the transmission from the satellite truck in New York City to the far reaches of the planet wasn’t about just the democratization of opera — it was an essential component of Peter Gelb’s long-term plan to save the Metropolitan Opera.

I had the life-jolting pleasure of seeing Aida at the Metropolitan’s Lincoln Centre home late last year. Its sheer scale almost defies belief. Can cinema ever hope to capture something so grand? I’m sceptical.

The ABC has a history of broadcasting theatre to lounge rooms, most recently Keating: The Musical and earlier this year Opera Australia’s home-grown Bliss. Cable stations like STVIO are also broadcasting live performance — both, admittedly, to tiny audiences (Bliss was seen by just a few thousand people nationally on the ABC’s digital-only channel).

And not just opera. The New York Times reports today that amid the battle between The Met and Britain’s Royal Opera House for movie-goers, the recreated Globe Theatre in London will now begin broadcasting its productions. Shakespeare on the silver screen — minus Gwyneth Paltrow. Would you watch a classical interpretation of the Bard up on screen without the usual movie trickery?

As a theatre-goer, do the world’s best theatrical companies beamed into your local playhouse hold any appeal? Or does the cinematic experience just not measure up to the real thing?

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.