Rebecca Arnold writes: Arriving in South Africa just three days after the chaos and excitement of the World Cup final, an air of exhilaration still lingered. A lone Spaniard greeted me at Johannesburg airport with a long blow of his plastic vuvuzela — whose ear-splitting blast had been until then, for me at least, only heard on television — and a great cry of “Viva España!” from the balcony above.

Our first stop was Soweto, that most famous township. Avoiding the the bus tours full of gawking tourists, my good friend Alana and I opted to gawk in a different way: on an eight hour walking tour. We wanted a chance to see Soweto and meet the people who lived there and hopefully understand a bit of this place which has played a fairly significant role in the formation of the nation.

The first adventure on the way to Soweto was figuring out how to use the minibus taxis that black South Africans use (white South Africans very rarely — if ever — use this method of transport, and we received looks of horror whenever we told people we’d ridden on them).

Our guide Ntombi with us but it still took a while to get our heads around the complicated hand signals that passengers use to indicate to the driver which direction they’re going in, and the incredibly honest payment system which sees people passing their taxi fare from person to person to the front of the bus and change passed dutifully back.

In the enormous taxi rank we swapped from one minibus taxi to another, and received the first of several marriage proposals of the day. We felt quite safe there — save for the hundreds of buses driving haphazardly around, often without care for pedestrians — but knew that the taxi ranks are the scene of several violent muggings (and often murders) each year, so were on guard. Earlier this year the taxi drivers went on strike when new, modern bus services were introduced ahead of the World Cup, burning tyres and shooting at the new buses, according to some papers.

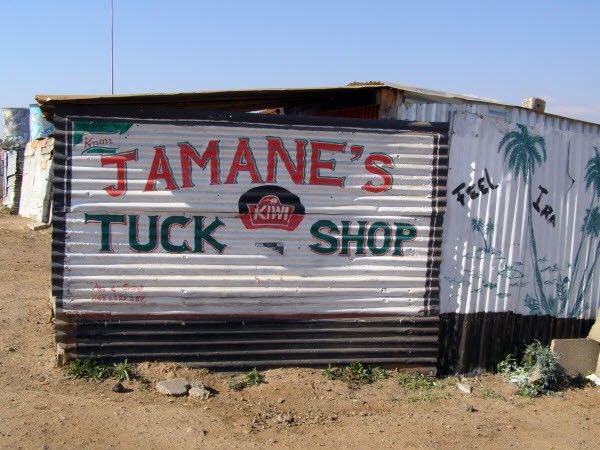

Driving past the now silent Soccer City on the outskirts of Johannesburg, where it sat like a giant red and beige mushroom cap on the barren landscape, we headed toward the bustle of Soweto. As we drew closer and entered the fringes of the township, houses past made of all types of materials: shacks thrown together with scavenged pieces of wood and cardboard, lean-tos hastily built with sheets of tin, bleak government houses of concrete and brick.

It was here that the stark inequalities that still exist between black and white in post-Apartheid South Africa were most apparent to me.

The tour took us to the key sights, like Vilakazi Street, the only street in the world to house two Nobel Prize winners, Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu. Not surprisingly, the streets are now paved and beautifully manicured, with Mandela’s original house serving as a museum. Past the brilliant colours of the power station cooling towers in Orlando we wandered. Through Walter Sisulu Square in Kliptown. To the superb eponymous Hector Pieterson Museum, a memorial for the 13-year-old boy who was killed when police opened fire during student protests in 1976. The students were protesting against the enforced use of Afrikaans in schools, and signalled the beginning of the Soweto Uprising. We trudged up the 49 steps of a tower for an amazing view over Soweto and the boarding houses that housed thousands of black workers as they all flowed into Johannesburg when gold was discovered.

We went from suburb to suburb, always on the minibuses, ticking off the sights that marked remarkable pieces of history. But what stuck most in my mind were the people we met along the way.

Strolling through the streets, we met people who wanted their photographs taken, posing solemnly as we obligingly pulled out our cameras. We walked between shacks and were greeted by people keen to practice their English and ask us where we were from, always smiling and nodding happily when we said Australia. They stuck their heads out of impossibly small houses and thanked us as we handed their children lollies. On the minibuses, we laughed with drivers as they laughed at our attempts to copy the taxi hand signals. We ducked our heads as we entered a shack, and spent a good hour playing a local card game with two guys and one of their little daughters, remaining completely perplexed by the rules up until we left.

But, most poignantly, I recall the man who walked up to our guide and earnestly shook our hands as he thanked her for bringing us there to show us where they live and how they live. Leading up to the tour, and even as we’d begun walking around, I’d had my doubts about the ethics of wandering through the township, peering into peoples houses and taking photos as they went about their daily business. Were we just like those people peering at Soweto from behind a glass window on a bus?

But on hearing those sincere words from a resident of the township, I realised that sometimes this kind of tourism is beneficial. It fosters understanding, when it’s done tastefully and respectfully. There’s a lot of debate about “slum tourism” and whether it’s right or not — think favela tours in Brazil or tours of slums in India. But we went to Soweto to appreciate and learn about an area that used to be in the media for negative reasons only, and got to interact with people, and have a tiny peek inside their lives — inside lives that other (can I say, more privileged) people who live in the country don’t even know about.

In the real world Rebecca Arnold is a Melbourne-based PR flack. She’s just spent some time volunteering in South Africa and writes about her travels at Rebecca and the World.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.