Australia’s poorest pay the highest effective marginal tax rates, leading to long-term work disincentives for welfare recipients, according to a brief released by The Australia Institute this week.

The document, Removing poverty traps in the tax-transfer system, will be submitted to the federal government in the lead-up to a new tax summit to be held by mid-2011, revisiting the Henry Tax Review. The review highlighted the anomaly, as did the incoming government brief (“red book”) handed to finance minister Penny Wong when she assumed the portfolio after the election.

According the brief, there’s a whacking great list of benefits that taper simultaneously when someone receiving benefits re-enters the workforce. This can lead to an effective tax rate of up to 100% for some, which translates to absolutely no financial benefit in re-entering the workforce. Welfare Rights Centre director Maree O’Halloran says the system is stacked against low-income families in particular.

“In the worst cases, an individual can face five different payments all tapering at once: Family Tax Benefit A, Family Tax Benefit B, Youth Allowance, Child Care Benefit, Public Housing. It’s like a house of cards, with the deck stacked against low-income families, unemployed people and secondary earners, usually women working casually,” she told Crikey.

A senior policy adviser at the Australian Council of Social Services, Peter Davidson, says if the structure tax system was changed, it would encourage more people on benefits to work: “The structure should be changed and extra work related expenses should be reduced. Income tests for Newstart Allowance should be reduced, and that overlapping of tapers should be removed.”

Single parent Susan Brown recently re-entered the workforce, and says she could never have afforded to work before her two girls reached school age. “I used to get $630 a fortnight now I get about $300 on top of which I have to pay for child care. If the girls weren’t in school, childcare would cost about $120 a day,” she said.

One of the most prominent poverty traps shown in the brief is that faced by public housing tenants, whose rent increases incrementally with their income. But O’Halloran says the disincentive to work starts long before welfare recipients actually take up tenancy.

“The workforce disincentives embedded in our public housing policies require urgent attention. If you’ve been on a waiting list for public housing for years you become very fearful about jeopardising your place in the long queue,” she said.

And policy manager at the Community Housing Federation of Australia Eddy Bourke told Crikey the problem is compounded by a chronic shortage of accommodation: “There’s a race to the bottom, when the state is only able to allocate housing to the very most vulnerable people in the community. People just won’t work if they think their chances of getting a place will be affected.”

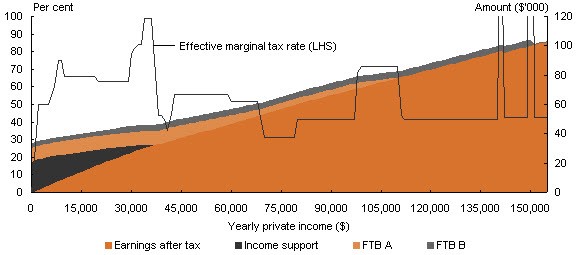

Catholic Social Services CEO Frank Quinlan says the problems created by the complicated tax-transfer system are not new, but that the report certainly highlights the stark disparity in effective tax rates faced by people on low incomes. This figure, first published in the Henry Review, shows the level of tax paid by welfare recipients as they enter the workforce. It’s based on the yearly private income of single income couple with two children.

Source: Treasury, Australia’s future tax syxtem consultation paper, Chart 4.5, p.94

This graph shows the effective tax rate for a family earning $30,000-$40,000 per year is over 90% when tapering benefits and income tax are accounted for. This compares with the 35% paid by a family earning $70,000 per year.

In response to the figures, the brief states: “It is relevant to ask why such an arbitrary pattern of effective marginal tax rates in the welfare system is tolerated when it is surely within the wit of policy makers to design system that claws back welfare entitlements and extracts tax in a smooth and consistent manner.”

The brief echoes changes to the interaction between the tax system and the welfare system called for by Treasury. Quinlan says while basic human dignity is being called for, there is also an economic imperative at stake.

“Purely from an economic point of view it makes sense to improve the standard of living for Australia’s poorest people, and help them into the workforce, rather than deterring them from entering it,” he said.

Whilst I appreciate the sentiments in the article, the commentary around the chart is misleadng.

There is a big difference between ‘marginal’ tax rates and ‘average’ tax rates.

The ‘marginal’ tax rate of 90% between 35k and 40k simply means that for every extra $1000 in revenue, the person nets $100 – a potential disincentive to working more hours or shifting to a slightly higher paying job. That said it is still more money in the pocket and once you get to ~$45k its much better.

Note that the average net tax for a person on $35-40k is probably zero once FTA/FTB are taken into account.

The big marginal rates are created by some of the brackets in FTA/FTB

(eg earn $149999 get FTB, earn $150000 don’t). The only way to get rid of this is for everything to be a smooth taper – but then that means the benefit is subject to the tax return and is then paid after the fact which may be worse for some of the people who need this payment.

After 11 years of the Coalition in govt, they never thought to work on this?

I guess it was a lot easier for them just to criticise those on welfare, and not actually look at a system that makes it hard for people to get off that same welfare.

When one looks at the funding forgone with negative gearing, subsidies to private schools, the rebate on private health insurance and other means by which those already well off have their grotesque noses in the trough of taxpayer’s dollars, you start to wonder what welfare is all about.

Not surprising. Ask anyone on long rem benefits whether it is worth their while to look for work and they’ll tell you the same thing. Why work 36-40 hours per week to take home an extra $20 or $30. And of course you lose all the wonderful benefits like cheap prescription etc. etc. etc.

The system has been unbalanced for a very log time — and everytime the Libs get into power they unbalance it more.

NEGATIVE….. Totally agree with your sentiments. It is high time the so-called Labor government started acting like one, and began dismantling these obscene middle-class welfare handouts. Because you have lots of money and can buy lots of houses (when so many people cannot even afford one) you get lots of rewards, viz: negative gearing. What a rort! And that is only one benefit worth billions of dollars a year the rich are given. There are many, many more. We sure do need tax reform in this country. But just watch the mealy mouthed politicians giving us unbelieveable/unintelligible reasons why business, big and small, and the wealthy need bigger tax cuts than the less fortunate among us. The response to the Henry Tax Review is predictable.