The dire state of debt-saddled Hollywood studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Inc (MGM), which has been tinkering on the brink of bankruptcy for the last few years, is now beginning the slow trek towards a financial second life.

The dire state of debt-saddled Hollywood studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Inc (MGM), which has been tinkering on the brink of bankruptcy for the last few years, is now beginning the slow trek towards a financial second life.

Late last Friday owners of the company’s whopping $US4 billion in debt voted in favour of a plan that will see it merge with Spyglass Entertainment, a smaller production studio buoyed by recent hits such as Star Trek and Get Him to the Greek.

The debt will be turned into equity under chapter 11 of the US Bankruptcy Code, which protects companies from creditors while they restructure/downsize.

MGM, which owns the rights to franchises such as James Bond and The Hobbit, said via statement released on Friday:

“The secured lenders voting in the Company’s solicitation process have overwhelmingly approved its proposed plan of reorganization (“Plan”). MGM will now move expeditiously to implement that Plan, which will dramatically reduce its debt and put the Company in a strong position to execute its business strategy.”

The only other widely reported option was for the studio to have been sold to 74-year-old billionaire investor Carl Icahn, who made two failed bids to buy up MGM and its debt – and already owns about US$800 million of it.

If the MGM debacle were turned into a movie, Icahn would probably be the villain. He is also the controlling shareholder of Lions Gate Entertainment Corp, the very company now suing him for what they claim was essentially an act of double crossing.

Lions Gate has accused Icahn of “making false and misleading statements” against propositions for a merger that might have reduced the value of his stocks, while at the same gunning for one that wouldn’t. It’s all very Gordon Gekko.

Says the Lions Gate federal court compliment, filed on October 28:

“Icahn opposed a merger with MGM not because it was bad for Lions Gate shareholders, but because it was good — so good, in fact, that he wanted to postpone it until he could buy as much of both companies as he could and thus extract for himself as much of the value stemming from the merger as possible.

MGM will have around a month to prepare for the transition, which will make Spyglass co-founders Gary Barber and Roger Birnbaum the new MGM co-CEOs. They are expected to focus on making more smaller budget releases to minimise risks and begin a slow dribble back into the black.

However, expect them to advance some of their investments as soon as possible: namely the as yet untitled 23rd James Bond movie and The Hobbit films, although Peter Jackson and co. have had their own problems to sort through before the cameras in Middle Earth roll.

MGM’s financial failings underline the volatility of the Hollywood studio system. The public tend to regard major production studios as monolithic Tyrell-esque corporations, which is true to a point, but it’s not unusual for Hollywood studios to end financial years in the red – effectively meaning they would have made more money collecting interest from banks than investing in film production.

The industry survives not by a consistent run of profitable ventures but by a small stable of titles that do remarkably well and generate long term investments. The truth about business in Hollywood is that most movies are not commercially successful – at least not during their theatrical run. Hollywood’s bread and butter is generated through “back end” deals: rights that are licensed and sold on cable networks, Pay Per View, DVDs, TV channels, merchandising and so forth.

A cursory look at the figures for, say, a movie that cost around US$150 million and generated US$300 million at the box office would suggest that it was a profitable venture for the production studio. But if taken at face value these numbers are grossly misleading, largely because they reflect the amount of money theatres take in rather than what studios earn.

Film distributors receive a portion of box office intake – usually somewhere around the 50% mark – and then deduct the cost for prints and advertising, which for major titles ranks in the tens of millions of dollars. Then other factors come into play: taxes, shipping, shares of profit assigned to producers, directors, stars etcetera.

On author Edward Jay Epstein’s excellent blog The Hollywood Economist, Epstein wrote a post in July explaining how Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2007) grossed more than US$900 million worldwide and two years later still remained “over 167 million in the red.”

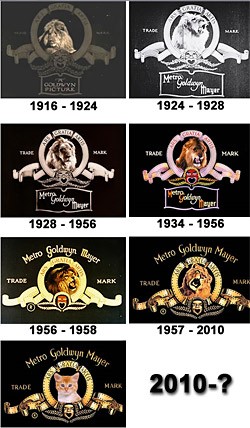

So while the newly tamed MGM lion may wish to get roaring on The Hobbit and 007, the zoo keepers understand they may not see real profits for some time.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.