Being a country local member has been a tough gig for the past two decades, especially for coastal electorates where successive governments have closed schools, shut down fishing fleets, “rationalised” the dairy industry, merged councils and privatised government industries in the hinterland. As a National Party MP in a Gippsland electorate, there is also the rapidly changing demographics — sea changers who, in the leader of the Victorian Nationals Peter Ryan’s electorate, can make up to 40% of the non-resident ratepayers in many towns — but his seat is safe.

He is typical of many Nationals who have thrived electorally because they engage with their electorate. He has fought many battles with locals, won some and lost some but he has always been in there, in and around the towns, ever present at public meetings, in cafes, pubs and general stores, in local papers and on the radio.

He has just issued a media release for his most persistent campaign — the re-opening of the Port Welshpool Long Jetty. It was suddenly shut in 2003 when it was decided that it was no longer economically viable for shipping. But Ryan argues that this jetty is worth so much more to the local economy as a key tourist attraction and one of the best fishing platforms on the Bass Strait coast.

Now there is a push to install an underwater observatory into the Long Jetty, similar to one installed on the Busselton Jetty in Western Australia, after a feasibility study and two business plans have highlighted the huge potential economic value of the Long Jetty with such an observatory.

From these studies we now know just how much money recreational fishfolk spend when they visit rural Victoria, from a study by Ernst and Young for Victorian Recreational Fishing — an average of $250 per day. With the Gippsland Lakes, Port Phillip Bay and Westernport suffering from crowded boat ramps and periodic environmental problems, Corner Inlet has become Victoria’s fishing hotspot with the Long Jetty Caravan Park at Port Welshpool hosting 80,000-100,000 visitor days of mostly fishfolk.

Though officially closed, many fishermen “jumped the fence” to fish from the jetty on days when it was too rough to go to sea. For the workers of the Latrobe Valley this is their best and closest marine fishing spot by far with runs of kingfish, gummy shark, trevally and flathead — penguins and dolphins are regular visitors.

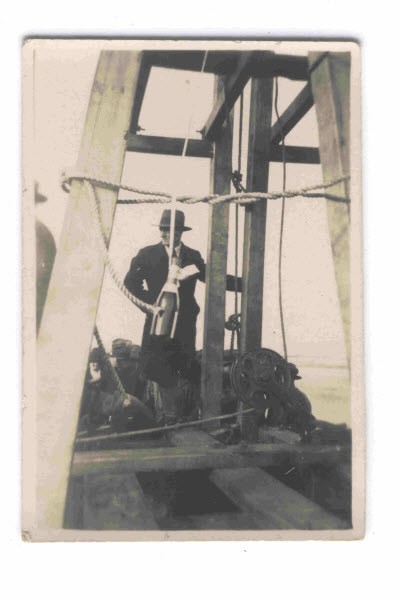

Port Welshpool is within sight of the northern most tip of Wilson’s Promontory. The Long Jetty construction began there in 1934 as a result of recommendations of a 1926 Royal Commission and it was completed in 1939. It was immediately put into service during the war to service the commandos, anti-submarine and military training facilities at Wilsons Promontory through to 1949.

It is built of long, yellow stringy bark logs cut from the local forest and it stretches in a long elegant curve out into the main channel that leads from these sheltered waters to Bass Strait. This port and jetty has long provided a physical and social connection from Victoria across the Bass Strait islands to Tasmania. This route was plied by sealers, then trading boats and fishfolk with all-women crews in WW2 when the Long Jetty was pressed into service.

The jetty was a focus for trading and fishing but has become increasingly important for recreational fishing and “strolling”. With a backdrop of Wilsons Promontory and winding its way for nearly a kilometre to the sea, this jetty was attracting many thousands of visitors annually — but no counts were kept as it was considered an industrial jetty.

The campaign to save the Long Jetty moved into overdrive last year when locals secured a deal with the company that built the Busselton underwater observatory, Marine & Civil, to build, own and operate a “three-storey” underwater observatory and then transfer its ownership to local community once it was paid off. What impressed this Western Australian company was the tourism potential and the incredible range of marine life that was resident under the jetty — especially the sea horses.

The Welshpool and Port Welshpool local communities have long worked together to survive when other small communities have been lost. They managed to establish and maintain one of the nation’s first Rural Transaction Centres — a small bank branch — bought the building and extended it. A closed agricultural supplier became an opportunity shop in weeks. It now hosts a range of government services and the local community is pro-active in promoting the area with an annual Sea Days Festival every new year, developing a shared pathway to the port along an old horse-drawn tram route.

Locals have a do take great pride in “their jetty”. 94-year-old resident Norry Rossitter took photos at every stage of its construction and talked proudly of the trouble taken to select the timbers from the local forest and the day it opened.

For Peter Ryan and the local Gippsland community, even if the Coalition does not form government after the election next Saturday, there will be no let up in the push to re-open the Port Welshpool Long Jetty and install an underwater observatory. For him and a growing number of people, such “country determination” makes the issue of opening the Long Jetty a matter of “when not if” — indeed the same could apply to the electoral fortunes of the Coalition.

I have to say that from all I’ve read and heard, Corner Inlet is one of the most tantalisingly curious and interesting Australian places I’ve never been. That long curving jetty looks like a fading tribute to a hands-on, practical past where honest physical toil could be measured in no-nonsense material accomplishment. Look, there’s the tall timber industry – in most of its twentieth century manifestations, run out of town for its not-inconsiderable sins. What is that wood by the way, and where did it come from? But also, there’s a reminder of the Latrobe Valley and its brown coal swamps and scorched-earth-for-electricity industry – surely something we wish we didn’t do, that we could have left behind last century?

I gather though, that there’s a colourful, thriving, surviving, commercial fishing fleet in there somewhere and I wonder how they did it?