Looking is tiring, isn’t it — I just want to shut the door and my eyes, and lie back into a soft, deep couch.

What did you see this year? Without notes I wouldn’t recall past back last week.

Here are my personal highlights for the year gone by:

+ + +

Winter’s Bone

Winter’s Bone

For me, the film of the year, actor of the year, director and screenplay of the year. Tenser than Hurt Locker, far more intelligent than Inception, more alien than Avatar, more revealing and relevant than The White Ribbon, more moving than, er, Iron Man 2.

Jennifer Lawrence as Ree Dolly is remarkable — “an almost-plain, scrubbed beauty who carries herself with a stubborn but vulnerable grace.”

(See Mulcher review.)

+ + +

Toy Story 3

Toy Story 3

A tie for the best film, though admittedly it’s more achieved. This is masterpiece cinema. It was the most moving and delightful and sad and joyous art movie of the year. It’s also among the most emotionally real of movies.

“Here’s another thing — somewhere in the last reel, in a passage of 10 or 15 minutes, the sense of tragedy and loss was so powerful, I found myself circumspectly sobbing.” Though the ultrasenior father-in-law did not.

Picture up top of the page is Woody, of course, horrified at things going wrong — which is the way most of the film goes. Part of its genius is that you get to smile and laugh despite the cascading mishaps, and horrors. Above left is Barbie and Ken who have a progressively subversive subplot in the film. (See Mulcher review.)

+ + +

Animal Kingdom

Animal Kingdom

Best Australian film since Samson and Delilah. Great story, fantastic narrative, wonderful acting, beautifully set and shot. Hats off to all the actors, especially Ben Mendelsohn and Jacki Weaver: Mendelsohn channeled Eric Bana’s Chopper, Weaver (right) invented something outrageous.

“Grandma Smurf. Jacki Weaver’s mesmeric crime den mother. With her mascara smearing: I can’t find my positive spin on this. And I’m usually really good at it. How she turns, and turns again, on a dime, on a bad penny.”

(See Mulcher review.)

+ + +

+ + +

Mad Men, Season 2 DVD

Season 1 was eye-opening, Season 2 was addictive — the Kodak carousel has become a screaming roller coaster. (And we’ve been queue jumping on the first few episodes of Season 3: even darker.)

Don, Betty, Peggy, Pete, Roger, Joan. What’s the secret? It is that ice cool and sleek surfaces hide the hearts breaking; but watch the little cracks spread. Joan’s mortification in Season 2 was played out in one of the most moving scenes I’ve watched on the box.

Advertising is about seduction and temptation; Mad Men is about the contradictions in the human soul. That wouldn’t work as a sales slogan, but at least has the virtue of being vaguely accurate. No matter, Mad Men needs no explicator, its exposition is clarity itself.

.

+ + +

The Thick of It, DVD

We enjoyed BBC’s The Thick of It in gasping, squirming, turn the face positions.

We enjoyed BBC’s The Thick of It in gasping, squirming, turn the face positions.

If you don’t know, Thick is a satire of (British) government. Yes, Minister was acerbic, but genteel. Thick is foul mouthed Doc Marten booting, it furiously hammers all the nails on the head. The embarrassment factor is high, the ferocity extreme.

If you hate politicians, you’ll love it. If you love politics, you’ll laugh yourself sick. Get Thick.

+ + +

Modern Family

What an accomplished work of ensemble brilliance! To arrive so fully formed and so tightly written is a TV fantasy; a fantasy for writers, performers, directors, executives and viewers. Very wicked and tack-sharp. The stereotypes are just sufficiently shaded so that the comic strokes have the blood of life, and when the jokes cut, the characters bleed, just a little. Bleeding funny.

+ + +

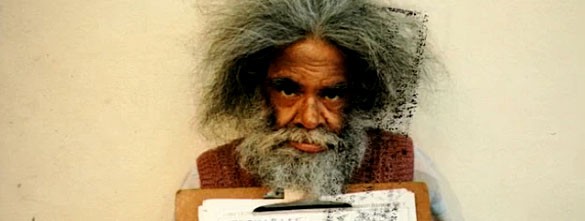

Bastardy

Bastardy

Watched this doco in a state of sympathy and concern for a smack addict. “Actor, cat burglar, Aboriginal elder” Jack Charles, who has burned a lifetime of talent and chances with drugs and jailtime, discovers in himself, through this documentary, a will to change the tragic trajectory. The actor is here acted upon — to conciously be observed is to be able to observe oneself too, a very hard trick.

In a similar way, Director Amiel Courtin-Wilson’s seven year following of Charles has resulted in a film which is, in a fashion almost too subtle to say clearly, briefly, its own subject.

The display and recordings of Charles shooting up is painful to watch, but in the service of verisimiltude, we witness it more than once. His homelessness is presented in a way which compels an understanding of how profoundly unsettling is the state of being placeless.

What makes the watching of the film tolerable is the chance to watch Jack Charles. If one can perform life, Charles does it. In a fascinating way, he is larger than life, all five foot four of him — his natural exaggerations draw the eye. At 67, Charles looks ten years older. But when he laughs, and he does loves to laugh, he looks like he embodies a benign spirit of the land.

(See Mulcher review of Jack Charles v The Crown.)

+ + +

A R T B O O K S

The Sight of Death, an experiment in art writing by T.J. Clark

The Sight of Death, an experiment in art writing by T.J. Clark

If you like classic art, and you enjoy the idea of, the talking about, the observation of the act of looking, this is your book. Written in a diary form over 240 pages, art historian Clark looks at — inspects — closely, minutely, two Poussin paintings at the Getty Museum in LA. He looks at them every day for three months (and revisits them briefly over the next two years).

The book is fully illustrated with details of the pictures accompanying the text references. It’s obsessive, it’s kind-of spaced out. Clark is superhumanly resourceful.

“And yet, and yet … The blue is impersonal and perfect. It is a work of the mind, which necessarily includes the hand and eye and their imperfections. I still haven’t found a word for this kind of paint application in Poussin, which is one of his characteristic achievements. (The dark brown of the washhouse in the water is analogous, and much of the modulation of gray — stone without sun on it — in the real-world architecture.” — 7 February

“Of course I am more and more aware as the weeks go by that what drives these entries onward, ultimately, is an argument with the present regime of the image — in particular with the notion that some kind of threshold has been passed in our time between a verbal world and a visual one. Not that the realm of language has proved dispensable for human beings … ” — 6 April

This is one way to look at art, and it tells you how only some art — the greatest, and of a certain kind: classic — could bear this kind of fanatical scrutiny.

+ + +

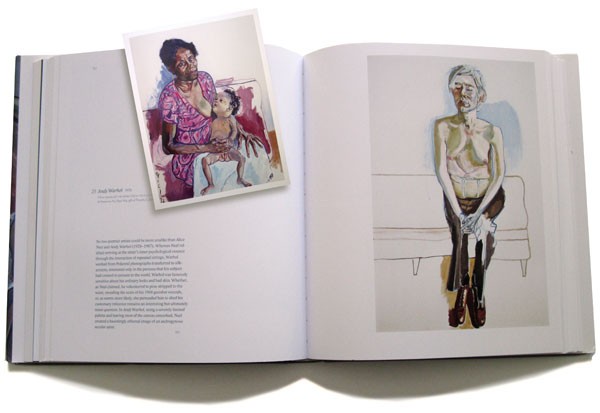

Painted Truths, Alice Neel, exhibition catalogue

A friend ranted about how the title of this book imposed a polemic on (the late) Alice Neel, how it distorted looking at her work. I dunno — Neel seemed quite capable of painting truths, and the title is rather banal. An-nyway, it’s the catalogue of the exhibition that travelled from Houston to London to Malmö, Sweden and the show I most wish I had seen. Neel is a great portrait painter, one of the handful best of the twentieth century, and I don’t know that anyone has been so much better in the past. (Yes, Rembrandt, yes, the Flemish.)

In the briefiest note in the catalogue, the great Frank Auerbach writes: “Alice Neel does not need my encomium … As I get older I feel, increasingly and dauntingly, that artists have to be heroes. Alice Neel is one of mine.”

(I don’t know why Auerbach should feel artists have to be heroes. Very odd. A very insular remark, even…)

In her essay, Marlene Dumas writes, “There’s been a lot of artistic talk about identity this last twenty years. Critics love the noun, placing the emphasis on the wrong spot. Alice used the verb. She identified. It is about identifying with, to find the right balance in the power struggle between the artist and her subject … She didn’t paint models; she didn’t paint monsters. She painted people.”

Alice Neel said: “I don’t do realism.” She also said: “I’m a collector of souls.”

Dumas calls the portrait of Andy Warhol, above, one of the most beautiful paintings of the twentieth century. The postcard on the book is Carmen and Judy, a portrait of Neel’s Haitian cleaning lady and her baby. Neel could do fame, but most of her pictures are of her friends and family. She did get real close, she put some of their soul into their portraits. See the Alice Neel website (with gallery).

+ + +

The Australian Ugliness by Robin Boyd — 50th anniversary edition.

“Indispensable.” Alan Saunders, “Remarkable.” Peter Conrad, “Endlessly quotable.” Gideon Haigh, “An inspiration.” Gutave Nossal. (See Mulcher story.)

+ + +

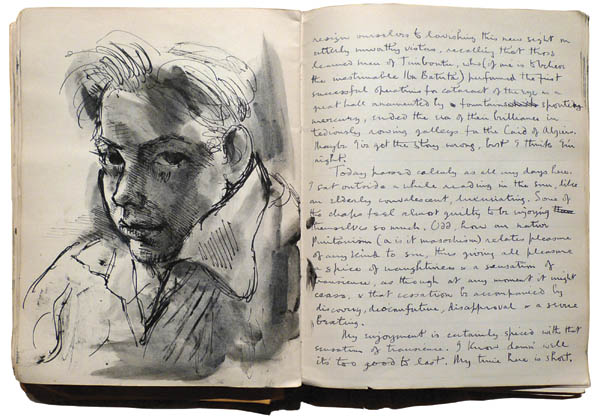

The Donald Friend Diaries, Chronicles and confessions of an Australian artist, edited by Ian Britain

“A brilliant and unique man.” — Barry Humphries

“There is nothing in Australian letters to equal his diaries.” — Robert Hughes.

“There is nothing in Australian letters to equal his diaries.” — Robert Hughes.

At age fourteen, Donald Friend declared: ‘Have done quite a lot of painting lately, and have made up my mind that I shall be an artist. And I shall be famous!’

Donald Friend kept his diaries over sixty years, from the age of thirteen till his death at 74. For those who were daunted by the big bricks of the four volume National Library edition, this book is a godsend, offering a narrative threaded from go to whoa.

Editor Ian Britain spent several years distilling the two million plus words down by 95%, which still leaves a rich, globe-trotting, name-dropping tale. The early self-portrait above, from a long-lost diary which amazingly Britain recovered in the US, has been reproduced as a facsimile spread in the book — there are over thirty pages of Friend’s marvelous illustrations. Friend led a complicated and now controversial life, but The Diaries is genuinely one of the great works of Australian art. This edition finally makes it accessible. I must add that I designed the book, but you musn’t hold that against it.

I’ve randomly plucked out three four entries (it’s like potato crisps, hard to stop at 1 or 2):

January 1943: Sydney. As soon as I am out of the protective sphere of the Drysdales, I am as alone as I was at first in London. The city is full of a foreign rowdy rabble, mostly American. Until very recently I never suffered from race prejudice. But I can’t stand all these Yanks about the place, corrupting everything like mad. I distrust their awful pink toothbrush outlook on life …

Dec 1957: Colombo in a ferment. Workers went on strike, so the city was without water, electric light, sanitation and garbage removers. Bombs were thrown and people killed …

3 March 1965: A dinner party at James Fairfax’s — for his mother to meet Patrick White. We faced up to him with some nervousness, as he can be — and is well know for it — devastating. But no one could have been more amusing … White gives me the impression of a man who keeps a tremendous store of power in reserve: a sort of quiet volcano. I don’t really like his books except for The Tree of Man and Riders in the Chariot.

24 January 1977: I am painting away every day on the big picture. I have been happy doing this work, feeling it must be important and yet it must be highly priced and is of a size few private houses these days could accommodate. And also the imagery of the subject matter is so outlandish that few of our very rich could stomach it. So in my mind the picture is somewhat unsaleable — which leaves me more free than I would be if money was in the back of my mind.

+ + +

Night Studio, a memoir of Philip Guston by Musa Mayer

Night Studio, a memoir of Philip Guston by Musa Mayer

A daughter’s memoir of a great artist, flawed heroic figure, mediocre father. Stunningly close to home, with a macro view of an artist’s life. Guston had a late, famously controversial return to figuration from expressionist abstraction, vindicated almost too late. And not only figures, but cartoons.

How he pressed on despite universal derision is the story of a phenomenal will; it is the same will that distorted the lives of his wife and daughter, and, if you like, his own too. For the love of art. Is even great art worth it? Musa, the daughter-author has . . . very mixed feelings. But she forgives and makes her peace in the course of this book. A touching account and as frank as it gets.

.

+ + +

Harland’s Half Acre by David Malouf

I didn’t read Ransom. I read this instead — as part of my project of reading novels about artists. Frank Harland, an artist, is based a bit on the romantic myth of Ian Fairweather. The book (1984) is terrific, Malouf’s light touch illuminating mid-20th century Brisbane and Queensland, and Harland is a great, twitchy loner, beautifully complicated by Malouf.

My proviso is that the writing about the art again falls into the trap: writers want to write a picture like an essay — it’s something you can’t do before the picture appears; everything written about it is post-facto; the conceptualists proved it can’t be done; or see Tom Wolfe’s wonderfully philistine and skewed send-up, The Painted Word. Georges Braque: ‘The painter thinks in forms and colors. The aim is not to reconstitute an anecdotal fact but to constitute a pictorial fact.’

+ + +

+ + +

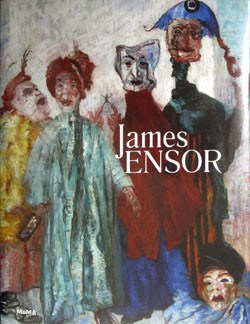

James Ensor, Anna Swinbourne, MoMA

Another northern hemisphere exhibition (2009) that would have been great to see. New York’s MoMA gave the late 19th century Belgian painter a good show by all accounts. This beautifully produced book was a revelation for me. Ensor’s work was sumptuous and powerful and varied and prescient.

An artist’s artist, Ensor was relentlessly innovative and original, all in the seaside holiday town of Ostend where he spent his entire life in his parent’s shophouse. He made satires and allegories, religious send-ups and metaphysical mysteries, he was a “painter of masks” and skulls, and made a lot of prints. And had one of the most vivacious of palattes. Check out his paintings at MoMA.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.