Natural disasters, especially those on the scale of the Queensland floods, generate an enormous amount of information — and misinformation — from official sources and from individuals on the ground. But this year, for the first time, a major media agency is attempting to make crowd sourced information a major part of its emergency coverage.

Emergencies catalyse our instinct to help people — and the information age has given everybody the ability, no matter how physically remote they are, to participate in an event and feel connected, says Anahi Iacucci, an expert in social media and the crowdsourcing of emergency information. The current crisis has seen a rush of people take to Twitter, local and remote, attempting to spread helpful information via hashtags #qldfloods and #thebigwet.

But with so much information available, picking out accurate and useful information is made that much harder. A few years ago, this would not have been a problem –the media and emergency services held a monopoly on trusted and accurate information. But they struggle to match the immediacy (and at times proximity) of crowdsourcing, so the temptation is there for people trapped in emergency situations to use crowdsourced information to make decisions.

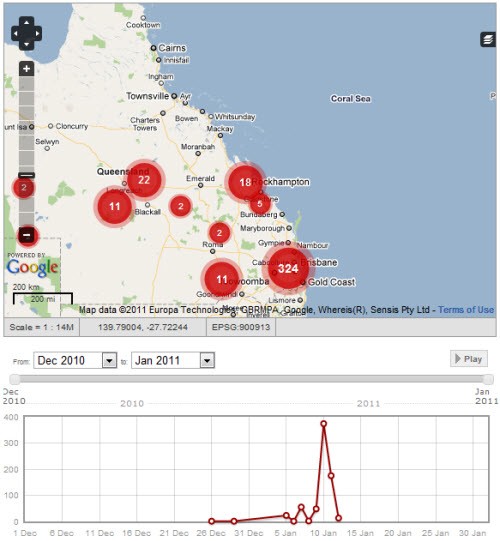

This year media groups such as the ABC are attempting to significantly integrate crowdsourcing into emergency coverage. The recently launched ABC Flood Crisis Map has been so popular that it spent large amounts of yesterday and this morning inaccessible as servers struggled to cope with demand.

The map can be accessed by anyone with an internet connection, and doesn’t require any software downloads. “It’s basically a messaging and message management site that allows reports to come in through a range of channels — SMS, email, twitter, online reports — and then has a moderation component where those messages can be verified, geolocated and then published on a map”, says Maurits van der Vlugt, a spatial information strategist, an expert in crowdsourcing emergency maps, and manager of BushFireConnect, a crowdsourced map for bushfires.

“What makes [crowdsourcing] effective is that it’s near instantaneous and it’s provided by people on the ground. It’s not an alternative to the official information sources that come from the SES and the police, but because they have a very strict and structured information management process, there is by necessity a lag before information trickles through that pipeline.

“The reason we started BushfireConnect was specifically in response to the demand from post-Black-Saturday bushfire recovery committees, where they said during Black Saturday the only source we had was the official agencies, and when they lost track and they got behind the fires. They said ‘we need something where we can share information with the next village or community, and it has to be immediate’.”

Verifying the information is key. Twitter has been abuzz with photos of kangaroos commandeering boats (a scene not from the current crisis), crocodiles coming ashore in Gympie (unconfirmed) and widespread talk of a public transport shutdown (not true; while ferries have stopped running and some sections of rail line was closed there is no system-wide shutdown).

Van der Vlugt accepts this as an essential and innate caveat of crowd sourced information, but says that some level of moderation — by the moderator and the end user — can be implemented: “You basically apply a bit of common sense. It’s easy to filter out the spam and the nonsense.

“There’s a number of quality indicators that you can apply: is it a trusted source, is it a well known source, is it verified? You can also vote up and down, as an end user. If you click on any of the reports … you will see a little vote-up vote-down thing … So if you’re next door to the report and you can see that there’s no flood there at all you can vote it down as not reliable and comment ‘this is a hoax’.”

The ABC map uses a similar moderation process, but has a special category on the map for trusted reports — those that come from emergency services.

“Most people are smart enough to make decisions based on the voracity of different information sources,” van der Vlugt said. “People now make decisions on what they do based on the information they get from the SES as well as stuff they overhear at the supermarket checkout. They are smart enough to understand the difference in reliability, but they also understand that if they hear something at the supermarket checkout and then read it on twitter then hear someone talk about it at school, they also understand that it’s probably true.

“Most reports come from individuals on the ground, and is placed on the map alongside information from media and emergency services.” Van der Vlugt says about a third of all information received is weeded out in the moderation process, and even more is removed by the crowd-moderation process.

ABC managing director Mark Scott recently issued company-wide social media guidelines; it’s not apparent how these guidelines — particularly No.3, which says the ABC must not appear to endorse personal views — apply to the crowdsourced map.

EveryMap.com.au is also mapping both the QLD & NSW Floods – locals can tweet using the #everymap, email us at info@everymap.com.au or send a report to EveryMap via the website http://www.everymap.com.au

Photos and video can be included in any report and you can join in a discussion on any of the reports.

Our site has not gone down & locals can get flood alerts sent to their inbox as soon as they are posted on EveryMap.

The EveryMap site has a section for Emergency reports – but is also designed so locals can report news & information on any local topic they want to share and get action on.

The floods are currently the dominant topic of interest / sharing on EveryMap but non-emergency news can also be shared and mapped.

For example, locals in Clovelly, Coogee & Bondi have been mapping the location of backpacker campervans that they want moved on by Councils.

All feedback & thoughts welcome.

http://www.everymap.com.au

Cheers

Angela

“Most people are smart enough to make decisions based on the voracity of different information sources,” van der Vlugt said.

Forgive my pedantry, but I presume he actually said “veracity”.

I also think we should be aware of the lack of data to build accurate pictures of what is happening. Particularly for those emergency planners that are not necessarily linked with any Government department (e.g. food relief organisations, hospitals, RSPCA and others).

I wrote a note about this and yes, I have maps in my website. The most recent depicts the locations of supermarkets in the affected areas, hoping to reach consumers that are looking for the nearest shop in their area.

http://www.food-chain.com.au/events/

Good to see so many initiatives. Crowdsourcing can work but these are only humble beginnings. As many probably experienced, current applications are not robust enough to handle peak traffic. Then there is the issue of “informative information” from submitted data, that is, current applications are not user friendly and would probably confuse and frustrate more people than win over and encourage to participate. Finally, there are no easy ways of dissemination and sharing of that information. So, there is still a long road to make it all working but certainly, community at large has a big role to play in the future.

Fortunately, big disasters are few and far between in Australia. But it also means that community do not have much “practice” in how to participate in crowdsourcing activities. Media like Crikey can play a big role in education and encouragement of participation because disasters of different kinds are always present. Just have a look on what was happening in NSW alone throughout 2010:

Map of disaster declared ares in NSW – 2010

http://ow.ly/3CQLn [shortened url to an interactive map for easy sharing!]

Arek

b: http://all-things-spatial.blogspot.com/

w: http://www.aus-emaps.com/