Much of rural Victoria is braced for flooding worse than even the oldest residents can remember. Hundreds of houses across the state’s north and west are under threat.

In Horsham, residents are tuning in to local radio for updates on road cuts, power outages and emergency service information. The situation is ever-changing, ABC journalist Emily Stewart told Crikey today, with the peak of flooding expected either this afternoon or tomorrow.

The town’s Weir Park, on the banks of the Wimmera River, is now flooded and “steadily rising” water has cut off some roads. The local council was this morning warning residents the rising waters could reach further than similar floods in September. Some 130mm of rain have fallen over the past three days.

No properties have been flooded yet, but Stewart reports 100 homes face inundation and as many as 500 properties could be flooded and isolate residents of the 14,000-strong community, 200km west of Melbourne. The local ABC studios, at least, are safe from the rising tide.

The Wimmera Mail-Times prepared its readers for the “one-in-200 year” threat this morning. It doesn’t publish again until Wednesday, but the newsroom is busily compiling information safe from the flood threat in the centre of town, a staffer said this morning.

Readers of the Campaspe News had to lean over sandbags at the front door of the newsagent in Rochester to grab a copy, with most of the town’s streets covered in water. Editor of the paper as well as the Riverine Herald, Annette Gregson, says these floods are “bigger than anyone can remember”. The little town of Rochester, population around 2000, experienced a peak of 9.17m on Saturday night, higher than the 1956 floods and putting a whopping 80% of the town underwater.

Echuca, where the papers are produced, is flooded right along the Campaspe River. Gregson says a lot of sandbagging is happening, but the river seems to have peaked and gone down a little, leaving 60 properties partially flood affected. The flooding hasn’t affected the production of local papers, thankfully, although it’s proven difficult to access parts of town.

Most of the media are focused on Queensland at the moment, but Gregson isn’t surprised: “It happened and then we happened. In Rochester it will certainly impact on a lot of people’s lives but no one is lost.”

Not that Rochester is being completely forgotten, with an emotional Gregson talking about the compassion that army personnel dealt with the local elderly and frail and volunteers helping out for long hours. And on the front page of tomorrow’s Riverine Herald? “Flood. Flood and flood photos.”

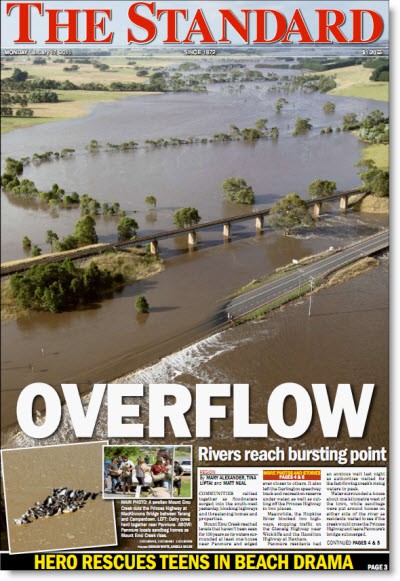

It’s the same in Warrnambool, with today’s Standard picturing the swollen Mount Emu Creek in the middle of the Princes Highway, between Terang and Camperdown. The highway has been closed since yesterday in two separate places.

One area of readership wasn’t able to get the paper today due to road closures, although the chief of staff at the daily, Shane Fowles, is quick to note it’s only one area of dozens of towns. The Standard, which covers south-western Victoria — from Portland in the west to Hamilton in the north and Camperdown in the east — is currently covering an area affected by flooding in both the Mount Emu Creek and the Hopkins River.

There are now evacuations around the Allansford region, just outside of Warrnambool, Fowles updates, but the Hopkins River is expected to drop this afternoon. Much of the flooding is around the tiny towns of Allansford and Panmure.

As for tomorrow’s cover, The Standard’s reporters are all out in the field today, so no idea yet, says Fowles. But with a relief centre in Warrnambool housing 10 people last night, “expect a few stories to come out of there”.

What we all mean of course is that it will be the biggest since white settlement.

The millions of years before that of course have no bearing on where floods might occur because white people didn’t experience them.

Honest to goodness, how about some real reportage.

Dont knock the reportage – its documenting oral history for when we are reading from silicon wafers, and needing to get our perception of what’s real by our google searches of the past. Reporting on reporting is a classic way of reportage post internet.

Sheesh (says I with tongue firmly in cheek), when you include the professionalism of some Bloggers you could almost say there is no point in you reading from this very virtual broadsheet Crikey!

Speaking from my own experience with design of bridges, which I did for only a few years in the 1960’s, the historical river levels were frequently referenced as indicators of the stream hights which could be anticipated.

Aboriginal oral histories of the “big one” or whatever it may have been called locally were corroborated by reference to driftwood found stuck in old trees, silt and debris up the banks and, of course, the oral histories passed down from the times before white settlement.

These were also statistically evaluated with reference to both the records of more recent stream flows and, by using normal hydrographic methods, calculation of probable runoff from hypothetical storm events and hydraulic behaviour of estimated by surveys of the valley and vegetation. The precipitation and timing of the storm events were calculated catchment by catchment from weather models of major storms.

Graphical modelling has given way to computer models developed since the 1960’s, but are still imperfect. My last training in this strand of engineering was during the mid 1990’s, so there has been almost 20 years’ further development about which I know nought.

So, I would suggest to Marilyn that she bear in mind that there are at least half a dozen different ways to predict maximum storm events and catchment bahaviour. It goes a long way beyond simply sitting beside a stream and counting the number of times your feet get wet in, say, 100 years.

At least in eastern NSW, the oral history of the aboriginals has been and, for all I know, still provides, one valued and valid indication of stream flow and flood height.