Last week I looked at the plummeting rates of attendance — and the various attempts by the Northern Territory government to address it — at remote schools in the NT. Today I want to have a closer look at one of those schools where these issues are crystalising into a crisis at the heart of the administration of remote education in the NT.

At 850 kilometres south-west from Darwin, and just a bit further from Alice Springs, Lajamanu is as about as remote as you can get in the NT.

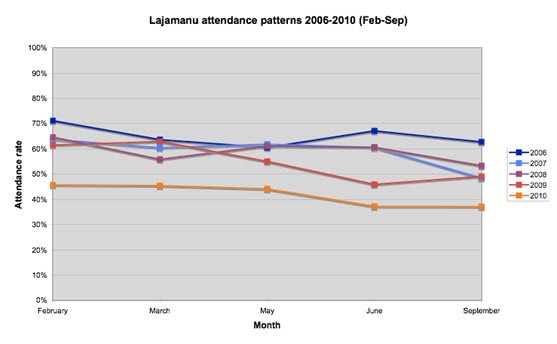

As this graph shows, attendance at Lajamanu School has been in freefall for several years. In the September quarter of 2010 the attendance rate at Lajamanu fell to 37% of enrolments.

Source: Greg Dickson, Australian National University

In September last year Lance Box, who had worked at a teacher in the bilingual program at Lajamanu between 2003 and 2008, returned to the community to visit with family and friends. Box was so disturbed by what community members, local elders and his former students told him about recent changes at the school that he prepared a report that he passed on to the NT government.

Box also provided Crikey with a copy of his report.

On his first night in the community, Box went to the community basketball court — formerly a hive of after-school hours activity and an informal community meeting place. He was surprised to find no one there other than three boys huddled under a blanket. He was horrified by what they told him.

Particularly concerning for Box, in light of the long history of bilingual education at Lajamanu and the pride that Warlpiri people take in their language and culture, was the assertion by the boys that “No Warlpiri language is allowed to be spoken in the school”.

Box notes that these statements “may not be fully factual, and may be embellished” but they gave him sufficient cause for concern and further investigation.

One community member told Box that the school gates were locked during school hours and that “no family members are permitted to enter the school grounds”.

The next day Box met with a group of senior male elders, who said that fundamental changes had been made to long-standing school practices and policies without consultation with the broader community and that some staff at the school had refused to engage in any meaningful way with senior elders — or the community as a whole.

There was more — much more — that for a variety of reasons cannot be more closely examined here. Lance Box concludes his report with a few observations of his own:

“Whether all or some of these allegations are true or not needs further investigation. Fact: There is a very high fence around the schools and all of the gates, except the main gate, were locked during our stay. The signs on the fences are not welcoming. Fact: Nearly everyone we spoke to has an opinion, and very few had a positive thing to say about the changes in the school. Fact: All the elders we spoke to were angry and offended by the way they had been treated … Fact: many of the Yapa [Warlpiri people] who were previously working at the school no longer work in the school. Fact: Non-Warlpiri people who made comment did so ‘off-the-record’ because they felt intimidated by school staff.”

Lajamanu school had for several years been cited as a model for successful bilingual education in the NT within a domain where bilingual education, as the 1998 Review of Remote Education by ex-Senator Bob Collins, Learning Lessons: An independent review of Indigenous education in the Northern Territory (“the Collins Review”) argued, had made important advances in remote education.

In 2001 the NT’s Country Liberal Party — after ruling for 27 years — lost power to Claire Martin’s Labor Party. For a few years, perhaps until the political and economic realities of remote service delivery in the NT hit home, there was a sort of “golden hour” for remote indigenous education in the NT.

Labor committed to many of the recommendation of the Collins Review and made several — albeit qualified — expressions of support for bilingual education. And early in Martin’s first term, a pilot program known as “Community Controlled Schools” was implemented. The Community Controlled Schools program appears to have disappeared without a trace within a year or two of its implementation.

The next attempt at “engagement” with remote communities on education was the “Remote Learning Partnerships” project, a complex an expensive project that at least two large cultural and language blocs — the Yolngu of north-east Arnhem Land and the Warlpiri from central Australia — engaged with in good faith and substantial vigor.

For the Warlpiri and Yolngu communities it seemed that — for once and not before time — the NT government was finally committed to meaningful engagement with local communities about the delivery of education on their communities.

The Warlpiri, particularly at Lajamanu, used the opportunities provided by the Community Controlled Schools and Remote Learning Partnerships programs to examine ways that Warlpiri philosophical and religious principles could be incorporated into a model that would provide connections between the mainstream education system and Warlpiri educational pedagogy.

This process was led by a wholly remarkable Warlpiri man. Steve Jampijinpa Patrick has worked as an assistant teacher at Lajamanu for more than a decade and in 2007 was awarded the Innovative Curriculum Award by the Australian Curriculum Studies Association in recognition of his pioneering work in the application of Warlpiri Ngurra-kurlu (the inter-relationship between Land, Law, Language, Ceremony and Kinship) to the task of helping Warlpiri people make sense of mainstream education.

You can see Jampijinpa explaining the Ngurra-kurlu philosophy in this short video here.

But, notwithstanding the many hours of hard work put in by Warlpiri people — and other groups including the Yolngu schools in north-east Arnhem land — and the considerable expense incurred and time commitment by the NT Department of Education to the development of the Remote Learning Partnerships they have never been implemented.

ANU academic Greg Dickson examined enrolment and attendance rates at Lajamanu since the effective abandonment of bilingual education there in late 2008. In his paper Dickson notes that:

“In justifying the policy, the Northern Territory government claimed bilingual education programs had a negative effect on attendance and enrolment. These claims have since been challenged … Two years after the effective abolition of bilingual education, attendance and enrolment data from four Warlpiri schools show no improvement in attendance rates and in some cases attendance rates and levels of student engagement that have reduced significantly. This data provides serious challenges to Northern Territory government claims that bilingual education programs have a negative impact on enrolment and attendance and suggests a re-evaluation of policy relating to bilingual education is required.”

Whether the NT government will listen, and respond to, the alarm bells that Box, the Lajamanu community, Dickson and others are ringing remains to be seen.

Over the past two weeks Crikey posed several questions to NT Education Minister Chris Burns seeking a response to the issues raised by Box’s report.

In response, Crikey received this comment from Burns’ media staffer: “We won’t be providing a response as it is for a blog website.”

Last week, in reply to a further request for comment, Crikey received the following from a spokesperson for acting Minister for Education and Training Kon Vatskalis:

“Attendance rates at remote schools is [sic] not good enough, and that is why the government has a new attendance strategy aiming to improve this. A range of new initiatives will be implemented in targeted communities, and based on their success may be rolled out to more communities. Attendance is affected by a range of factors such as weather, ceremonies, funerals and transiting between remote and urban areas. The Every Child Every Day strategy includes programs to address these factors. An extensive communication strategy using local languages, advertising, text and voice messages will also be used.”

No further response has been received to repeated requests, including earlier today, for a response to the allegations and issues raised in the report by Box and provided to the NT government in October last year.

Crikey also made several attempts to contact the Lajamanu school by telephone without success.

Margaret Banks, take a bow. What a fine job you’ve done.

When I was in Lajamanu in October, the school looked like a prison – I’d back up Box’s comments. It was a pretty grim looking place. It was not what I was expecting.

I can’t comment as to whether they have stopped allowing Warlpiri language to be spoken (it would not suprise me) but the arguments against bilingual teaching seem completely without basis. It’s constantly disappointing – when it comes to policy, it feels like we are turning back the clock in these communities.

You have, of course, contacted Genereation One who aims to turn around the high absenteeism at Remote Indigenous Schools (RIS) in one generation…and Fountain For Youth (FFY) Ian Thorpe’s charity, where people like me who wish to do something practical for our own indigenous young, can provide Literacy Backpacks designed to help these young ones WANT to go to school…This needs much more advertisement and help from people such as Crikey.com let’s get this movement off the ground…

Joan Croll

It’s a fundamental rule that when dealing with Indigenous people you do so in a collaborative way. If this is not done then the chance of failure is high because you do not understand what it is you are dealing with, as with any problem which is poorly understood. To pretend that you do when you don’t, well, that’s too much self-confidence and arrogance for my liking. Unfortunately it is difficult for Indigenous people to assertively put forth their views thereby allowing government to get away with what it does, and what it has always done. I wish someone could change this.