The Garnaut Climate Change Review delivered in 2008 was a massive document — 630 pages — and possibly too much to digest, comment on and report on in one go. Professor Ross Garnaut clearly thinks Australia has been a slow learner, so he plans to deliver his 2010 update in installments, ensuring that the eight principal points he wishes to expand upon get due attention.

The update will be a crucial component of the public discussion that will surround the government’s proposals to introduce a carbon price, and Garnaut wants to raise the level of the debate, and to make sure the logic of his recommendations are well understood, even if people don’t like the conclusions.

The first instalment was delivered last night in Melbourne, at the Monash Sustainability Institute, entitled “Weighing the costs and benefits of climate change action”. Garnaut wants the logic of taking action to be understood. It’s been one of the sticking points: why should people pay now when the benefits will not be realised for another generation? Why should Australia take action when others are not? Why take any action at all when there is so much uncertainty about the impacts? Should we spend on mitigation or adaptation?

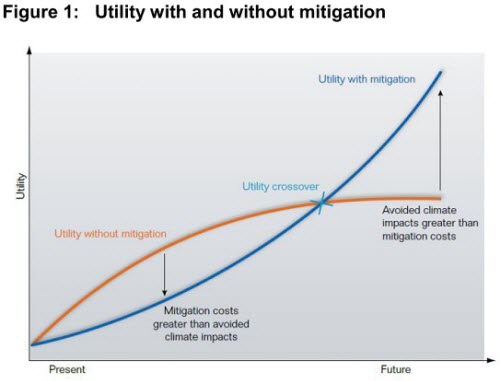

To answer the first and most problematic of these issues, Garnaut invites us to consider a graph in the shape of a fish, where the body represents the part of the graph where the cost of action taken is more than the benefits, and the tail, the point from where the gains outweigh the cost. It would be nice to think we can have a very small body and a very big tail, but it’s not quite so simple.

The tail has been made bigger by the realisation that the climate change impacts are at the higher end of predictions and, while the body has been made smaller by the unexpectedly steep fall in anticipated costs for clean energy, this has been countered by policy delays, which most models tell us will make the costs of action more expensive.

Part of the justification for determining the size of the body — and the tail for that matter — comes down to an assessment on how much the current generation should pay for the benefit of those that follow. In economic speak, this translates back into the discount rate. It is used by corporations to assess the future value of a dollar spent or saved now.

Garnaut argues that few older Australians would be willing to discount heavily the welfare of their grandchildren‘s generation relative to that of their own, and says the only justification for valuing the wellbeing of those in the future less than our own is the belief that humans may suddenly become extinct. And while the Mayans have an apocalyptic vision for 2012, not many others do.

The second consideration is whether to impose costs on the current generation when it is generally assumed that future generations will be richer. The problem here, Garnaut suggests, is that there is no longer any certainty that future generations will be richer than us (and therefore more able to absorb the costs of climate action), because of the potential impacts of climate change – a lack of environmental services being one of them.

As for the uncertainty about climate change impacts, Garnaut argues that this increases the case of more spending rather than less. We are usually prepared to insure against the worst outcomes, he says. It strengthens the case for action.

To explain why Australia should do its fair share, he pointed to the decision to send troops to Afghanistan. Contributing such a small contingent was not likely to change the outcome, but it was part of Australia’s proportional effort.

Meanwhile, Australia remains one of the highest emitters per capita. “If one of the rich countries doesn’t do its part, then we’ve got Buckley’s of getting the whole world to participate,” he said. “We should stop being a drag on the international effort.”

And on the question of whether to spend on mitigation or adaptation, Garnaut says it should be both. Adaptation investment is already occurring in the forms of desalination plants and the like, but Garnaut says it is cheaper to make investments in advance rather than trying to rescue the situation after catastrophes have occurred. “I can’t see the logic of saying there is choice between adaptation and mitigation.” If we don’t act, the adaptation costs will be huge.

Garnaut will likely expand upon these points in coming installments, and he gave an insight to some of his thinking in a briefing with journalists in Canberra on Thursday.

Installment No 2 will be on international action. Garnaut says that, while it is clear that the world has not obtained the international agreement that many had been hoping for at Copenhagen, what has been obtained at Copenhagen and Cancun may lead to more substantial results. “Let’s not pretend that nothing is happening. Some parts of the world are doing more than I expected.”

No 3: Global emission trends. Garnaut noted that the IPCC, IEA and other organisations had grossly underestimated the emissions path of the major developing economies – not just China and India, but Africa too; their rate of growth, their energy intensity and their emissions intensity, even if the emissions growth of the developed world was stalled by the global financial crisis. “The international community has been kidding itself” on emissions growth, Garnaut says.

No 4: Rural land use. While the original review talked “speculatively” about the potential of bio-sequestration, Garnaut says the science has moved on rapidly and it’s worth an update to see what’s feasible. It’s a big issue for Australia, one identified by the government in its Carbon Farming initiative.

No 5: Climate science. Garnaut says the latest IPCC compendium was published in 2007, but effectively only included peer reviewed science up until about 2005, and he intends to look at what’s been added since that time. He says it’s a “pretty sad” story. Recent data and events have confirmed that the IPCC report, if anything, underestimated the climate change impacts on global temperatures, sea level rises, and the intensification of weather events. He says climate sceptics cannot draw any strength from the “real science” of the past five years. “I wish that were not so.”

No 6: Approach to carbon pricing. It is clear that the government is now favouring some sort of hybrid system, a fixed price that can then mutate into a cap-and-trade system if the circumstances allow. This was Garnaut’s original suggestion, and he says he has no reason to change his position. He did say that a cap-and-trade scheme would only be appropriate if there was sufficient depth in international markets, and that does not appear to the case at the moment.

No 7: Innovation policy. Garnaut is frustrated that many of his recommendations on the need to support innovation, R&D and commercialisation of new technologies, which he says could have been funded by the sale of permits, did not get much traction with the government. “There’s lots of opportunities for low emissions technology in Australia,” he said. “We can be world champion in low emissions, just like we are for fossil fuels.” This could be true for nuclear, solar, marine, wind and algae.

No 8: The electricity sector. This, Garnaut concedes, is the politically hardest corner of the debate, particularly with the recent focus on electricity prices. He says the price rises that were foreshadowed in the 2008 review have come to pass, and they have nothing to do with mitigation costs, but are the results of increased capital costs from the resources boom, the higher cost of skills, rising coal prices, the internationalisation of the gas market, and increased transmission costs. “We will look at how much of that (transmission investment) is necessary and how much is the result of poor policy.” And the review will also look at the case for structural adjustment, or compensation.

*This article was originally published on Climate Spectator

yawn

Well, the results of listening to denialists’ lies and obfuscations for the last 15 years are upon us. Astro’s ‘yawn’ is baffling …

http://www.independent.co.uk/opinion/leading-articles/leading-article-beware-the-collapse-of-the-planets-lungs-2203576.html

This is a substantive contribution to public policy debate – Rip van Winkles can go to sleep (see above) while the adults get on with a substantial matter of public concern.

Ironic that Garnaut “explains” climate change costs to the “slow learners” of Australia with a fish-graph. This is the same Garnaut involved with the worst-polluting mine in the world (Ok Tedi) and the maritime dumping of toxic waste (Lihir Gold). We need a dead fish graph: the number of Garnaults by the size of the fish-kill.

The Greens’ abandonment of the real environment in favour of climate millenarianism is paralleled in Garnaut. Garnauit is their ally, when he should be anathema.

As for the assertion that “the unexpectedly steep fall in anticipated costs for clean energy” makes renewables more attractive- it shows just how far from reality the climate cult is: apart from nasty nuclear, not one renewable energy technology is remotely economic. Most are not proven at scale. Wind, the greatest current waste, is several times the cost of any FF and useless because of intermittency. Wind generates political, not electrical power.

See Garnaut for what he is: a patronising, egotistical salesman. He’s made a career of retailing successive issues du jour to our politicians. Masquerading as an intellectual titan, he has no trouble bluffing the low-rent opportunists of the ALP, not least the banal Julia. Even the Australian Right seems cowed, the pugnacity of Abbott being no compensation for his technological and economic ignorance…

(what happens when you lock Abbott and Gillard in a room with a computer? Plausible answers: (i) Sex, resulting in irreparable damage to the Toshiba (ii) Sex, followed by sleep. Computer untouched. (iii) A chaste, collaborative but ultimately unsuccessful search for the power button…)

Mitigation is supposed to be reducing GHG in a technical way, rather than reducing emission, and adaptation is living with the results? Ok, but how does that give us utility on the y axis? Is there a formula somewhere that combines mitigation and adaptation and cost? As usual, the comments degenerated rapidly into spiteful name-calling, which is hardly useful.