Ireland’s election produced very much the expected result, with the governing Fianna Fáil party — blamed for the country’s recent financial woes — sustaining the heaviest defeat in its history and losing about three-quarters of its seats.

But coverage of Irish politics — even in countries such as Australia, where many have Irish ancestry — has always been hampered by two things: its exotic electoral system and its exotic party system.

The electoral system shouldn’t be a problem for Australians, since it’s basically Tasmania. Tasmania elects its lower house from five electorates with five members each, by proportional representation; Ireland, with a similar area but nearly 10 times the population density, has 43 electorates with at most five members each (a number have only three or four) and the same voting system (known internationally as the single transferable vote, or STV).

In Tasmania, smaller electorates are a recent innovation, introduced in the 1990s to try to sideline the Greens; the state will return to seven-member electorates at the next election. But Ireland seems to have no such concerns — there are still 17 three-member electorates, where the quota for election is as high as 25%.

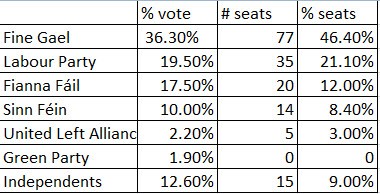

Despite that, regional variations balance out to produce a generally proportional result. Here are the provisional figures from the weekend:

The largest party, Fine Gael, will be over-represented, but not nearly as much as it would be in a system of single-member districts. If Ireland had the same electoral system as Britain or Canada, Fine Gael would almost certainly have won a substantial majority in its own right; now it will have to form a coalition, presumably with its long-time ally the Labour Party.

Ireland’s party system, on the other hand, is genuinely odd. Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil are separated not by their class basis or by economic or social policy, but by their positions on the Anglo-Irish treaty of 1921 and consequent civil war of 1922. Fine Gael is the descendant of the pro-treaty forces who accepted the gradual path to Irish sovereignty; Fianna Fáil represents the anti-treaty forces, who lost the civil war but have dominated Irish politics since the 1930s.

Categorising this in left-right terms, as commentators like to try to do, is fraught with difficulty. Fianna Fáil is traditionally more nationalist and pro-Catholic, but also more interventionist on economic policy. Fine Gael tends more to liberal internationalism and anti-clericalism (hence its relationship with Labour), but is also seen as more pro-business and sits with the centre-right in the European parliament.

In recent years Fianna Fáil has identified itself more with pro-market policies, but this strategy came to grief with the financial crisis. The middle-class vote has swung strongly back to Fine Gael; Labour, with its best result ever, has consolidated the urban working-class vote, and Sinn Féin, whose vote also increased sharply, has become the more natural home for the nationalist vote.

It looks as if Fianna Fáil could be squeezed out, and Labour may eventually replace it as the main rival to Fine Gael. But not too much should be read into one election; parties often come back from near-death experiences (Canada’s Conservatives are an obvious example), and Ireland’s electoral system makes it difficult for a party to be wiped out (although the Greens have managed it this time around).

It’s also worth remembering that anachronistic party systems often have a remarkable capacity for survival: witness Australia’s, still based on the class struggles of a century ago. Maybe we shouldn’t be quite so sceptical about Ireland.

Alas, no longer. In a calculated piece of populism, a couple of weeks ago the Lib Opposition withdrew from what had been tripartisan support for this measure, on the spurious grounds that the budget situation meant it couldn’t be afforded. The ALP gutlessly followed suit, saying that this made it ‘impossible’ to proceed, even though the Greens (with whom they control the lower house) still support it.

A fair article, Fine Gael also has strong links with the agricultural sector in Ireland. Charles if you can explain the Irish senate how it elects members etc i will be very impressed. From my experience the more you try to figure it out the harder it is

@Mark – thanks, my bad; I hadn’t seen that. Mind you, it’s more than three years till the next election, so there’s plenty of time for one of them to decide they need to appease the Greens & change their minds again.

@Walker – no, someone else can take on the senate; I think I’ll quit while I’m ahead.

Australia’s main parties still reflect class interests, altho not as clearly as previously.

Will attempt to explain the Senate:

Seanad Éireann (i.e. Senate of Ireland) is the upper house of the Oireachtas (Parliament) with 60 members who are appointed by a shemozzle of a system that laughs in democracy’s face. Essentially, of the 60:

– 11 are appointed directly by the Taoiseach (PM)

– 3 each are elected by the graduates of the University of Dublin and the National University of Ireland (total of 6)

– and the other 47 are appointed by a complete rort of a system whereby TDs, Senators and local councillors vote for nominees from five “vocational panels” (Administration, Agriculture, Education & Culture, Labour, Industry & Commerce). These panels are meant to be made up of people with relevant experience or knowledge of the field, but is usually just made up of party hacks that don’t have the patience or skills required to rustle up 20% of the vote in the bogs of Roscommon or Sligo.

FG, SF and Labour have all had long standing policies to abolish the Seanad. FF had been a hold out, but finally came around during the election campaign in what was presumably a vain and pointless attempt at attaining relevance. So it would appear that Seanad Éireann’s days are numbered.

Personally, I’m not a fan of unicameral parliaments, but given that the Irish electoral system makes a single party majority very difficult to attain, the lose of the Seanad without replacement won’t be such a disaster.