Just one month to go now. New South Wales goes to the polls on 26 March in an election whose result is probably more of a foregone conclusion than any in Australia in living memory.

The opinion polls have continued to show swings of an almost unbelievable magnitude. Newspoll this week put the Coalition on 62% two-party-preferred, a swing of just over 14% since the 2007 election. Essential Research had similar figures last week, and AC Nielsen showed an even more remarkable 18% swing.

Even assuming there is some correction in these figures during the campaign — which is likely, but by no means certain — Labor is on track for its worst result in New South Wales in more than a century. Anyone unfamiliar with the party’s record over the last four years can get all the gory detail from Antony Green’s summary. New South Wales voters come to elections with low expectations, but even their patience has been well and truly exhausted.

For a time it looked as if there might be a small glimmer of hope for Labor in the personal popularity of premier Kristina Keneally, but even that seems now to have evaporated. Newspoll puts her satisfaction rating at just 30%, down from 47% a year ago, and she trails opposition leader Barry O’Farrell 32%-47% in the preferred premier “beauty contest”.

One factor might be said to remain in Labor’s favor — the fact that the electoral boundaries are strongly weighted against the Coalition. This was its problem at the last election, when a very respectable 3.9% swing yielded a net gain of only two seats.

In 2007 the Coalition won 47.7% of the two-party-preferred vote. But a uniform swing of a further 2.3% would not give it anything like a majority — even with the rural independents it would only have 42 seats out of 93 (Antony Green, of course, has the pendulum).

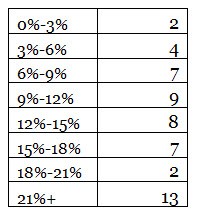

The swing will be a lot more than 2.3%, but only when it gets above about 6% are there large numbers of seats that will fall. The following table shows the number of Labor seats at risk for each 3% of swing. (Each seat is treated just as Labor vs Coalition, so independent or (potentially) Greens seats are counted according to the underlying two-party vote.)

There’s nothing sinister about the way the boundaries have been drawn, it’s just that New South Wales is demographically more stratified than Victoria or Queensland, so there are more suburbs where one or other major party is uncompetitive. That translates to fewer marginal seats, and because the Coalition’s safe areas are a bit safer than Labor’s the overall balance tilts Labor’s way.

If you’re defending against a moderate swing, that sort of weighting is tremendously valuable. Labor could potentially hang on with only about 47% of the vote. But in the current situation — where no-one expects the swing to be less than 8% — it does more harm than good, because the seats bunch up in exactly the part of the pendulum where the swing is likely to be.

Fewer marginal seats means more seats in the fairly safe bracket, but “fairly safe” for NSW Labor isn’t safe at all. In just the 1% band of swing from 10.1% to 11.1% there are seven Labor seats — more than in the whole section below 6%.

Swings are never uniform, so even if the overall swing is in the neighborhood of 10%-12%, there will be some seats on 15% or more that will be lost. And because there are so many of them there to start with, the Coalition will have a embarrassment of riches in terms of which seats to target.

That makes life difficult for Labor — not in terms of trying to win the election (an objective they will have given up on long ago) but in trying to preserve a viable caucus in opposition. Being reduced to fewer than twenty seats would consign the party to irrelevance, whereas holding onto more than thirty would be something of a triumph. But in trying to achieve that its defensive resources will be spread very thin indeed.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.