Here’s one reason why the budget isn’t bouncing back into surplus as fast as it went into deficit. From around the middle of the decade just gone, each time they looked in the kitty, the Coalition government found another five or so billion dollars … which they proceeded to spend on any number of improvised giveaways.

My favourite was John Howard’s 2004 promise of $800 to apprentices for a “tool kit”. The improvised giveaways did no lasting harm; one off raids on the budget’s bottom line. To look on the bright side, being timed to the electoral exigencies at hand they cost no more than necessary to achieve the desired (temporary) electoral effect.

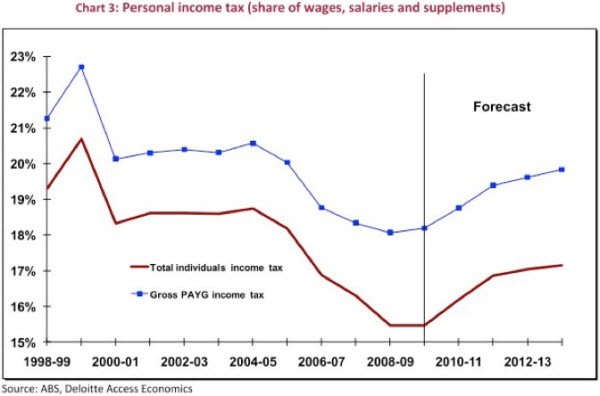

But in addition to all those improved cheques in the mail the Howard government began rebalancing the budget more permanently. With company tax from miners in the minerals boom Mark I growing like topsy it began a tradition of tax cuts that gave back far more than fiscal drag. The result, captured in the chart below from Deloitte Access Economics Budget Monitor, was a trend decline in the proportion of personal income paid in tax.

The bids in the auction were matched by Labor — as oppositions do — though right at the end, when they thought it might work for them, Kevin Rudd announced dramatically that the reckless spending had to stop. The ALP honoured the tax cut promises that had aped the Coalition’s promised tax cuts.

The graph also shows how things will improve if the government sticks to its intention of not cutting personal taxes until it’s firmly in the black. But the low level of personal taxation has reduced the kick the budget would normally have got from increasing employment (by around $10 billion dollars). Deloitte Access calculates it will still be costing the budget $6.3 billion in 2012-13 when we’re forecast to return to surplus.

And the new volatility of our budget is another threat to that much-awaited day when the 2012-13 budget surplus is finally in the can. This is nicely illustrated in a couple of cameos in the budget papers’ sensitivity analysis.

Scenario 1 looks at the downside of a fall in the terms of trade of just 4%. This cuts nominal GDP by one percentage point. We are then taken on a tour of that impact through the Treasury model. Lower mining export receipts reduces company profits, lower equity prices and resource rent tax collections. This then runs through to lower employment, wages and consumption.

This takes $6.3 billion off the 2012-13 budget bottom line. Given that it’s currently forecast at a $3.5 billion surplus it goes into a deficit of $2.8 billion. And that’s in response to a change in the terms of trade of just 4%!

By contrast scenario 2 sees the economy hit by a “good news” story of the same order of magnitude as the bad news story above. Participation and productivity each grow by 0.5% producing a 1% GDP gain. The impact on the bottom line? An improvement of $4.4 billion.

With the budget’s revenue depending much more on company tax — a much more volatile source than personal tax — the budget was always going to become more risky. But if the scenarios are anything to go by our budget isn’t just riskier. The surprises on the downside might end up doing more damage than surprises on the upside to good.

The OECD asked countries to increase their public debt to 60% of GDP. No company would dream of following a no debt policy as it would then be underutilising its resources. So why is Australia so fanatical about having zero public debt?

Chargre2, first of all the issue is not whether a government should be carrying debt on its balance sheet, but whether it should be funding its popularity by increasing that debt by $50 billion–in a growth year, during a once-in-140-years terms-of-trade boom, at a time when we are near full employment and the reserve bank is getting concerned about inflation. That is a good description of a time for government to back off and let the post-crisis business environment regroup with minimal inflationary crowding from government.

Second, there is also good reason to carry minimal debt on the balance sheet if the country does not need it to survive, and that is risk management. The next GFC or natural disaster may not be decades away, it may be next month or it may be tomorrow, and one of the reasons Australia is acting so smug now is that it entered the crisis with a positive balance sheet–as of 2006 the Australian government was lending more money than it was borrowing. The stronger your national credit rating is, the more you are able to borrow, at lower cost, when you really do need it.

Your complacency indicates that you neither know nor care just how hard it was for Australians to pay off that debt through work and taxes during the preceeding decade, perhaps you think Rudd just majicked a strong balance sheet into existence in 2007.

Mr Gruen, what’s the point of mentioning Howard’s $800 tool rebate for apprentices–some of whom borrow more money for the tools necessary to learn their trade than they make in a year on apprentice wages–as if that were comparable to a $400 giveaway on digital receivers for pensioners to watch the footy?

Also Mr Gruen, did you just commit the classic journalese of describing tax cuts as “spending”? And your graph fails to mention GST, which from FY2000/01 partly replaced income tax as a “proportion of personal income paid in tax”.

Also, as I mentioned above, Howard/Costello delayed further income tax cuts until FY2005/06 when they completed paying off $90 billion of the $96 billion in debt left behind by their predecessors, enabling Keating’s tax cuts to resume. The remaining $6 billion was paid off the following year, making Australia one of seven countries in the OECD that were lending more than they were borrowing, which came in very handy in 2008-09.

You make it sound as if these tax cut schedules were a burden left behind to hamper Labor in coping with the GFC, which could not be further from the truth.

Freecountry, thats DR Gruen to you. Twice. No dount Nick is too nice to point this out, I’m not. Before you accuse a proper economist of speaking journalese check some basic biography. FFS.

Point taken, Jeff, and thanks for the correction. And I know Dr Gruen is a heavyweight or I would have given him a free pass for appearing to neglect the relationship between income tax and GST.