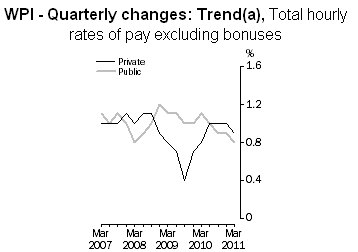

Modest wages growth. There was nothing that should cause panic at the Reserve Bank in Australian Bureau of Statistics wage price index figures released this morning.

Total hourly rates of pay in the March quarter were up 1% on the December figure. The annual trend growth figure showed an increase of 3.9% and the trend in the quarterly figures 1s down not up.

The fall in the Westpac-Melbourne Institute consumer sentiment index in May to its lowest level since June 2010, also out this morning, is another sign that the Australian economy is not yet in the conditions for an inflationary take-off.

Never look on the bright side of life. I’m not exactly sure why it is but journalists — and I am as guilty as the next one — tend to give more prominence to gloomy predictions than cheerful ones.

You can see examples of the phenomenon on most days but rarely as dramatically as in The Australian this morning with its gloomy headline:

To give an even gloomier complexion to the report of a speech by Treasury Secretary Martin Parkinson in which mentioned the possibility that if Beijing persists with manipulating its exchange rate and spreading inflation throughout the world the Chinese boom could turn to bust with serious consequences for Australia, the paper’s resident gloomster sprang into action:

Michael Stutchbury seems to take a positive delight in pointing to those things that might go wrong when my experience of things economic is that predictions are just as likely to be wrong because events turn out far better than expected than they are wrong because they turn out worse. But “Great news for Australia as the Chinese boom rolls on” just wouldn’t be as good a headline would it?

Undermining the wisdom of crowds. I will be in serious study mode considering the implications of a publication by mathematician Jan Lorenz and sociologist Heiko Rauhut of Switzerland’s ETH Zurich, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The two academics apparently have raised some serious questions about the impact that the sharing of knowledge through the internet might be having on the the wisdom of crowds.

The report I have read suggests that when people can learn what others think, the wisdom of crowds may veer towards ignorance.

A summary on the Wired Science website says that in a new study of crowd wisdom — the statistical phenomenon by which individual biases cancel each other out, distilling hundreds or thousands of individual guesses into uncannily accurate average answers — researchers told test participants about their peers’ guesses.

As a result, their group insight went awry.

“Although groups are initially ‘wise,’ knowledge about estimates of others narrows the diversity of opinions to such an extent that it undermines” collective wisdom. “Even mild social influence can undermine the wisdom of crowd effect.”

The effect — perhaps better described as the accuracy of crowds, since it best applies to questions involving quantifiable estimates — has been described for decades, beginning with Francis Galton’s 1907 account of fairgoers guessing an ox’s weight. It reached mainstream prominence with economist James Surowiecki’s 2004 bestseller, The Wisdom of Crowds.

Study participants were asked how many murders occurred in Switzerland in 2006. At the end of each round of questioning, they were given small payments for coming close to the actual answer (signified by the gray bar). At left is the range of responses among participants who received no information about others.

As Surowiecki explained, certain conditions must be met for crowd wisdom to emerge. Members of the crowd ought to have a variety of opinions, and to arrive at those opinions independently.

Take those away, and crowd intelligence fails, as evidenced in some market bubbles. Computer modeling of crowd behavior also hints at dynamics underlying crowd breakdowns, with he balance between information flow and diverse opinions becoming skewed.

I will report further when I have studied the original.

“I’m not exactly sure why it is but journalists — and I am as guilty as the next one — tend to give more prominence to gloomy predictions than cheerful ones”

You ought to know by now, bad news sells – “If it bleeds, it leads”.

Old hat, “herd mentality”. “Learning what others think” can be be used to reinforce one’s “precognitions/prejudice”, to reinforce one’s idea that one is “right, after all” – it’s proven : look at the way Limited News “works”?

Never look on the bright side of life?

News Limited needs Prozac.

Stutchbury’s “fearful” approach was entirely confected and designed, as is everything News Ltd put so prominently on their front page, to impugn Labor. In fact he distorted what Martin Parkinson said or intended. In the same speech Parkinson noted that 40 years ago when 40% of our exports were to one country, the UK, no one panicked about such a situation, so today when our exports to our leading trading partner are not even close to that level of dependence seems overdone. And in case younger Crikey readers have forgotten, it was Whitlam who dragged this country into accepting the reality of us being in Asia, after decades of stultifying Liberal rule intent on tight ties with old England (which had no compulsion in dropping us when they joined the EU).

But what should depress us all is that the first China boom was frittered away by Howard and Costello, and the same neanderthals (including many of Stutchbury’s colleagues) still resist a MRRT that would recover more of these windfall profits to reinvest in our future. So that when any downturn comes, or long-term some of these resources will not be required in the same quantities, we will have something more than lots of very big holes in the ground all over our country.