“Due to its decentralised nature, the internet per se is in fact extremely robust and resilient as it was designed to withstand nuclear war. However, separate parts of this network of networks are vulnerable to cyber threats. The most disquieting feature of the cyber domain is that the attacker has the advantage over the defender. Perpetrators need only one weak point to get inside the network, while defenders have to secure all vulnerabilities. These attacks also take place at the speed of light which leaves little or no time react to attacks. Furthermore, the inherent nature of the internet allows an attacker to [disguise] the true identity of an attacker and leading to misattribution of the source of an attack. The problem of attribution is widely recognised as the biggest obstacle for effective cyber defence.” — Lord Jopling, Special Rapporteur, NATO, May 2011.

Defending against government attacks on the internet is open to anyone online. It’s open to you, now. On the internet, the line between being a spectator and a participant in history is far easier to cross than in the real world.

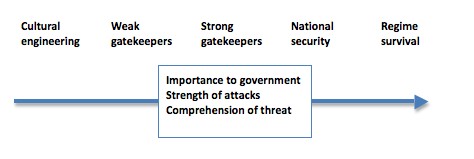

The first step in defending against government attacks on the internet is to get a sense of perspective. Earlier in this series I suggested this spectrum of government attacks:

You might argue with where to place various forms of attack on that spectrum, but plainly what is being done by regimes such as the Chinese, Syrian and Iranian dictatorships to dissidents — murder, r-pe, torture, imprisonment — is far beyond the threat faced by Western citizens from their own governments, which are far more heavily restricted by the rule of law — even if a government such as that of the United States persistently flouts its own laws.

And, I’d argue, the national security-sourced attacks on the internet pose a far greater threat than those posed by cultural engineers who, for example, want to ban, and often have succeeded in banning, gambling or p-rnography. Stephen Conroy’s proposed internet filter is bad policy and an affront to free speech but it’s not the end of the world. Extending ASIO’s powers to spy on WikiLeaks, and spy on Australians supporting WikiLeaks online, is a far more serious threat, and one that has received far less attention or outrage from the online community.

One of the keys to responding to government attacks on the internet is outlined by Lord Jopling above (the quote is taken from his recent “let’s get Anonymous” memo to NATO). He offers good advice to us, if you flip his memo around and regard governments as the ones posing the online threat.

I suggested yesterday that modern governments had an advantage over their predecessors of previous centuries in that they now have a serious capacity to monitor real-time interconnectedness. Regimes in previous centuries couldn’t monitor every workplace discussion, but they can try to monitor internet traffic. But attribution is not merely, as Lord Jopling notes, the biggest obstacle to cyber defence, it can be a big obstacle to governmental cyber attack. Online anonymity is a crucial defence against governments, and the more ferocious the attacks, the more important it is.

Simple-to-use, effective anonymisation software is therefore a holy grail of defence against online attacks by governments. Hillary Clinton — representing the split-personality of an administration that simultaneously avows its support for internet freedom while aggressively conducting its own wars online — announced in February $25 million to fund such tools against “internet repression”.

The State Department has a poor track record on such technologies — it endorsed Haystack, which turned out to be deeply flawed. The nearest widely available tool we have at the moment is Tor (one of whose developers, Jacob Appelbaum, is systematically harassed by the Obama Administration). Tor has its vulnerabilities, and doesn’t encrypt traffic, but is relatively close to plug-and-play, and can be used to provide anonymous bandwidth for users in other countries for whom keeping their identity secret is a much more serious matter than it is for most of us. Even if you never use it, downloading and running Tor potentially helps whistleblowers and dissidents stay safer online.

Of course, it can also used by criminals, filesharers or the local p-edophile, too. Said Clinton: “On the one hand, anonymity protects the exploitation of children. And on the other hand, anonymity protects the free expression of opposition to repressive governments. Anonymity allows the theft of intellectual property, but anonymity also permits people to come together in settings that gives them some basis for free expression without identifying themselves. None of this will be easy … We should err on the side of openness and do everything possible to create that, recognizing, as with any rule or any statement of principle, there are going to be exceptions.”

But online anonymity isn’t a 0 or 1 scenario, and doesn’t only apply for online dissidents trying to avoid local security forces. You may want to be anonymous for some activities and not for others. For the latter, minimising the amount of information you make available about yourself online is a good idea per se to reduce the chances of identity theft and prevent companies such as Facebook monetising your privacy by selling details about you to advertisers.

But it also reduces the effectiveness of data mining and scraping techniques that collect often otherwise insignificant pieces of personal information (for example, your IP address, what time you logged on to a site or made a comment, which individuals you are friends with or follow in social media) from as many sites as possible to put together a profile about you. This was the technique the notorious Aaron Barr of HBGary was using to compile a profile of Anonymous members for the FBI.

But the technique is also used by marketing companies and identity thieves. In short, when you go online you leave a lot of data around even without intending to; cutting that data to a minimum makes it harder for anyone — would-be identity thief, governments, marketing companies — to track you. But as Jopling says, you need to have only one vulnerability for the predators to exploit.

Does all this sound paranoid? Never for a moment forget that companies, security agencies and political parties want to profile you — yes, you — as much as possible. It’s usually not for outright malicious reasons, but it’s never in your interests.

The other thing you can do is to take advantage of the centrifugal nature of the internet. Whether you know it or not, it has empowered you and you should use that power. How? One of the traditional safeguards against governmental overreach is a watchdog media, a role an increasingly partisan and under-resourced mainstream media is less able to play than in the analog era. And for some attacks on the internet, much of media is incapable of playing a watchdog role because those attacks are being undertaken at their behest or to their advantage — think attempts to impose mainstream media regulation on the internet (our own anti-siphoning laws) or the British media backing judicial calls for social media to be censored over superinjunctions.

So become the media yourself. Connect up. Circulate information. Encourage transparency by sharing links to material that governments would prefer remained obscure. Break the ridiculous laws of other countries that stifle free speech (it’s far easier than you think and can be done from your home computer). So you’re only one person and you’ve only got 200 followers on Twitter? So what? That’s the point — that’s how this network functions effectively. That’s its resilience.

History shows that powerful élites eventually adjust to the impact of interconnectedness. They do so partly because they work out how to cope with, and even work with, what emerges from interconnectedness. And they do so because while individuals are weak, the networks they form are strong and resilient and motivated. And this time around, the numbers of people connected up are on a global scale. And you’re one of them.

“Ask not what the internet can do for you, ask what you can do for the internet”?

Doesn’t quite have the same ring to it.

Excellent series, thanks Bernard.

After the Internet, there’s only one last step to full interconnectedness, that of humanity developing some sort of borg-like hivemind, and considering how much we value our individualism, I think the Internet will be around for a long time. We should all try to look after it.

All Watched Over by Keanes of Loving Grace

Bernard is certainly correct about Tor.

It is reasonably simple to set up.

Since Sunday my anonymous bandwidth (a small amount) has been used by people in:

Cuba / China / Russia / Iran / Kuwait – presumably to evade repressive control

to communicate with France and the United States

It is a practical way to assist dissidents.

Yes a great series and I agree with Julian re Tor. I have been toying with the idea for a while but haven’t yet acted on it.