Atop the roof of Darwin’s Northern Immigration Detention Centre (NIDC), Habib Habiburahman sits in protest. He has entered day five of a hunger strike in an attempt to raise awareness of his situation after having spent the past 18 months in indefinite detention as an asylum seeker.

When I met Habib in February, the late afternoon monsoonal rain of northern Australia teemed outside one of the Northern Territory’s ubiquitous demountable buildings within the NIDC compound.

Inside, Habib sat with his head bowed. Hair neatly slicked back, face clean shaven. Outside, lines of razor wire and palm trees were visible through the haze.

“When I was 16, the Burmese government destroyed my family’s home,” so begins Habib’s story.

An ethnic Rohingyan, Habib was one of 14 in detention in Darwin. All had been granted refugee status, most in May 2010, yet they remained languishing in indefinite detention, awaiting the completion of ASIO security checks. Most had been in detention for more than a year.

The indefinite waiting and lack of information on their cases had begun to take a toll on the group’s mental health. Four of had attempted suicide. Last year one man tried to hang himself. Another set himself on fire. He was later told that he would be charged with destruction of Commonwealth property. Self-harm is common and most of the Rohingya intermittently refuse food or medical treatment.

Louise Newman, chair of the Detention Health Advisory Group for the Department of Immigration and Citizenship and Professor of Psychiatry at Monash University, said suicidal thinking can spread among detainees in such situations.

“This is very concerning from a mental health perspective,” she said. “This type of condition can be contagious. I am very concerned there are people having suicidal thoughts.”

Professor Newman sees acts such as self-harm as the classic responses of people suffering from traumatic experiences and possessing no sense of control over their lives.

“They’re isolated,” she said. “People feel abandoned and cut off. It reflects human distress when people feel confined and have no control over their lives.”

Habib described the assessment process as a Kafkaesque nightmare of bureaucratic procedure with no clear structure and ever-extended timeframes. “We are told all the time by the department that our cases are being processed,” he said. “But we witness other people released by Immigration. In some cases they have not been reviewed by ASIO.

“The people that try to kill themselves feel they are against powerful government organisations. This is their way to resist.”

This year ASIO has come under increasing scrutiny for delays in processing security clearances for refugees. At a Senate Estimates committee in February, Immigration officials revealed there were 900 people across Australia found to be refugees but left in indefinite detention as they awaited the completion of ASIO checks. This represents 13% of the population in Australia’s overcrowded detention system.

Last year 811 complaints were lodged with the Inspector General of Intelligence and Security for delays in the completion of security checks. In a letter to Habib the Inspector General, Dr Vivienne Thom, did little to offer guidance or assurance on the processes at work for those awaiting ASIO clearance.

“ASIO has advised me that the complexity of security assessments can vary and this makes it difficult to provide exact timeframes for completion,” she wrote. “The best way for you to obtain information about the overall progress of your visa is to contact the Department of Immigration and Citizenship.”

Since then, the Department of Immigration has outlined a new ”triage method” in a letter to the Human Rights Commission — ASIO staff no longer directly carry out security checks for the bulk of asylum seekers, which are instead now delegated to immigration officers.

As reported by The Sydney Morning Herald in late May, the Immigration Department says it will further speed up the new system to introduce a ”same-day service” for security checks.

But Habib expressed frustration at the indefinite waiting. “The Immigration case managers tell us they have no up-to-date information on our cases,” he protested. “We want to know what’s happening in the process or any problems our cases have. There are no groups in our country like al-Qaeda and no other armed groups so we can’t understand the delays.”

On February 2, the Rohingya were told they would have a chance to present their case to Immigration Minister Chris Bowen when he visited Darwin’s detention facilities.

Habib said he was among a group taken to a room and told to await the minister’s arrival.

“In the afternoon we could see the minister leaving and were then told he was not allowed to meet with anyone,” he said. “We felt like it was a conspiracy and became angry. We ran out of the room and climbed to the roof of one of the buildings and began shouting. Finally a lady came to get the letter. She told us she was the assistant secretary for Minister Bowen.”

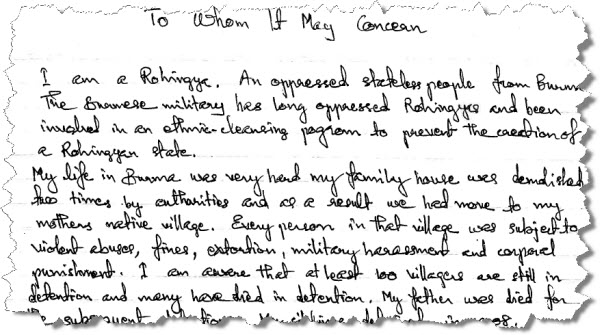

The letter read: “We understand the importance of people passing security clearances, however we do not understand why ASIO has taken so long to process our applications and are dismayed at the lack of information provided to us by the Department and ASIO regarding our security clearances.”

The Rohingya are stateless people. Human Rights Watch describes them as one of the most persecuted groups in Burma. “Even in Burma’s dreadful human rights landscape, the ill-treatment of the Rohingya stands out,” a 2009 report says. “Religious repression is widespread, with the military destroying many mosques … extrajudicial killings are common.”

There are no known Rohingyan terrorist groups.

After being beaten and tortured and by Burmese authorities in Rangoon, Habib trekked across the country and escaped into Thailand in 2000. From there he travelled to Malaysia where he spent 10 years. While able to work as an electrician, he lived with the constant fear of deportation. Malaysia is not a signatory to international refugee conventions and people fleeing to the country face abuse at the hands of immigration officials and the notorious vigilante groups.

“I was deported from Malaysia four times,” he said. “Each time we were captured we would be beaten and taken to the Thai border. There we were sold to people smugglers who would demand money from us and then take us back into Malaysia.”

On one occasion Habib was unable to pay Thai people smugglers and he was sold into slavery aboard a Thai fishing boat. He spent two months aboard the ship before escaping.

In December 2009, Habib undertook the dangerous sea journey from Indonesia to Australia.

“It was five days at sea,” he says. “The engines broke down and we had to steer the boat as the driver was only a teenager. We thought we would die. When we saw the patrol aircraft we cried with happiness and waved our clothes at it.”

Despite his experiences Habib is determined not to let his current circumstances break him.

“I do not want to attempt suicide or cut myself,” he states. “My way is different. I don’t want to be a victim and I will struggle to reveal the reality of our lives. For me that is more important now than the visa.”

Habib said he would like to see a judicial review of the processes of mandatory detention. Professor Newman agrees that mandatory detention is a failed policy and called on Minister Bowen to treat a review of the policy as a priority.

“We need to radically rethink the policies of detention,” she said. “The majority of people’s claims can be processed in the community. Other countries that function with community detention systems don’t have the rates of mental health problems we see as people can live with a sense of purpose.”

Habib agrees. Describing the case of a fellow Rohingyan now in community detention, his face lit up.

“This man tried to hang himself last year,” he told me. “Finally he is in community detention and he is very happy and healthy. If we were in community detention we could wait 10 years for our security check.”

Richard Ackland points out this am that this cruel stupidity is now costing $2 billion per annum while 9 million kids per annum die of hunger or preventable disease.

Bowen thinks he can illegally drport people to Malaysia in breach of Australian law and one can only believe he chose to do dirty deals with Malaysia because Malaysia are happy to collect $300 million and simple deport the poor people anyway.

He is worse and more ignorant than Philip Ruddock because he knows very well he is breaking the law and doesn’t care.

http://www.chrisbowen.net/media-centre/allNews.do?newsId=2061

Mr BOWEN (Prospect) (10.17 a.m.)?In 1951 the United Nations convention for the protection of refugees came into force. The world realised the mistakes of the 1930s, when many Western nations turned their backs on Jews fleeing persecution in Germany. Collectively, we said, ?Never again.? I am sure that all of us involved in public life would like to think that we would have done the right thing in those circumstances and stood up for those facing the worst of circumstances, regardless of whether it was popular or unpopular. If the Migration Amendment (Designated Unauthorised Arrivals) Bill 2006 passes the parliament today, it will be the day that Australia turned its back on the refugee convention and on refugees escaping circumstances that most of us can only imagine. This is a bad bill with no redeeming features. It is a hypocritical and illogical bill. If it is passed today, it will be a stain on our national character. The people who will be disadvantaged by this bill are in fear of their lives, and we should never turn our back on them. They are people who could make a real contribution to Australia.

This bill represents an extension of the so-called Pacific solution, in which we saw individuals who were processed offshore being treated differently from those processed in Australia. The Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs said in his second reading speech that the offshore processing system had preserved ?Australia?s strong commitment to refugee protection?. He is wrong. Let us take a look at how the Pacific solution has worked in practice. This bill extends the Pacific solution, so it is legitimate to look at how it has worked up until now. Firstly, we have seen families of refugees broken up?callously and in contravention of the refugee convention. Spouses of people who have been recognised as refugees in Australia received correspondence from the Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs, which has been reproduced by Michael Gordon in his excellent book Freeing Ali . It states:

Your claims have been assessed separately from your husband?s claims because you travelled at different times. Under the conditions of your husband?s stay in Australia he is not able to sponsor you. Like all refused asylum seekers you cannot remain in Nauru indefinitely. You should consider voluntary repatriation now.

What a callous piece of correspondence. I agree with Michael Gordon, who said of that letter:

There was only one conclusion to draw: if you wanted to be reunited with your husband, whose fear of persecution if he returned had been judged to be well founded, your only choice was to return and to convince him to leave Australia and confront the very danger he had fled.

Of course, several asylums on Manus Island and Nauru have had their applications rejected three, four or five times, only to have the government eventually accept their claims. Unlike people processed onshore, people processed offshore have no access to professional assistance. It is hard enough for a well-versed Australian native to understand Australia?s immigration system, let alone somebody with obvious language difficulties who is attempting to come to grips with the massive change in their circumstances. Of course, asylum seekers offshore have no right of appeal to higher authorities. McAdam and Crock highlighted the importance of this in an article in the Australian on 15 May. They said that between 1993 and 2006 the refugee tribunal overturned 8,000 determinations by departmental officers to refuse asylum. Asylum seekers who arrive in Australia by boat will not have this right of appeal if this bill is passed.”

Of course he now has the department deliberately denying most asylum seekers who arrive by boat, he then has to face the fact that most have then been overturned on review and he has to face the fact that refugees have the right under our laws to arrive and ask for our protection without being persecuted or pushed back to any other place.

Suicide prevention in detention is now all the go. If you dont show for breakfast lunch and dinner- name ticked off list- a guard tracks you down and asks why.

If no show for two meals in a row – called to interview at which you may be asked to sign a letter stating that ‘ I will not commit suicide” and warned.

If you are not seen by a guard for two hours your room will be entered without permission to check on you.

Room searches arbitrary, random , daily.

HIGH IMMINENT ALERT status means that you have a guard following you at one metre all day, even toilet.

Next one down means that you are followed and questioned after any activity.

Sleeping during the day is the only escape and is why people sit up at night and sleep all day.

No mater how miserable or depressed, no treatment beyond watching , surveillance and control.

Every step of the way this guy has acted in a completely understandable and human manner. Of course, he hits Australian shores and is confronted with “tough but humane” approach that robs him of dignity and many of their sanity. It’s enough to make me ashamed of Australia, the ignorance of the average Australian and (in particular) the disgusting political rhetoric that surrounds this issue.

I’ve been having a bit of a chat today via another Crikey article with Sandi Logan, DIAC’s peripatetic PR man.

Sandi agreed that it would be useful to have a few more faces and stories attached to the issue of asylum seekers to get away from the hard-hearted statistics, but that there were sensitivities about asylum seekers’ rights to privacy.

Well here’s a story, a face that doesn’t seem too concerned about his privacy.

What’s worse, making the wrong decisions and having them reversed in the Refugee Review Tribunal, or not making a decision at all?

But says Sandi, DIAC takes its “service delivery to clients” very seriously indeed.

Indeed?

Where are you Sandi?

Privacy is a lie, they just don’t want us to know that refugees are humans.