There has been much recent criticism of the analysis of the Norway massacre, particularly of the premature reporting of the atrocity as an Islamist terrorist attack. Many of these same analysts switched to psychological explanations after the right-wing political motives of the killer — anti-Islamism amongst them — were well established.

Discussion of the commentary has been marked by a preoccupation with terminology. Among others, Glen Greenwald, Waleed Aly, Guy Rundle (here and here), Charles Richardson and Tad Tietze have all pondered why there has been such a reluctance to call Breivik a terrorist.

Aly wrote:

There’s a problem here, and it has nothing to do with political correctness. It’s not even simply about public language. The problem is that the more we explain away acts of domestic terrorism as isolated cases of madness, the less capable we become of spotting it. Having realised the weekend’s attacks in Norway weren’t Islamist, we must do better than lazily assuming Breivik is just Norway’s answer to Martin Bryant.

In other words, the problem lies in our taxonomies of violent acts. A crazed killer cannot be predicted, prevented or negotiated with. But extremist agendas can be brought into the spotlight for public scrutiny before they find inarticulate expression in violence. Making the wrong diagnosis could lead to dangerous inertia. Greenwald argued in Salon that the word ‘terrorism’ has been manipulated to the extent that it “has no objective meaning and, at least in American political discourse, has come functionally to mean: violence committed by Muslims whom the West dislikes, no matter the cause or the target.” The repeated association between Muslims and ‘terrorism’ that Greenwald decries in America corresponds to what the linguist George Lakoff and others call ‘framing‘, or ‘re-framing’: the selective filtering and packaging of an idea to promote a particular interpretation.

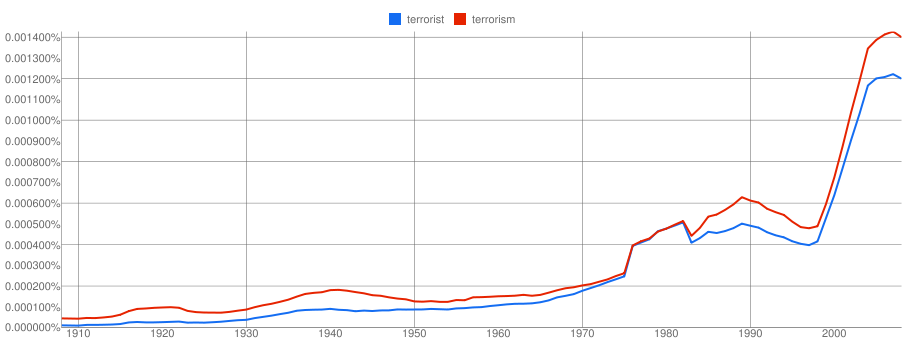

Applying a very blunt culturomics method I ran the words ‘terrorist’ and ‘terrorism’ through the N-gram viewer, which counts published uses of a term in Google Books within a given date span. A curious spike showed up in the early 1980s and the trend doesn’t pick up again until after 2001.

Who were these ‘terrorists’ referred to between 1975 and 1982? A spot check of the books archived by Google in this period shows that most of the references are generic and don’t tend to specify individual organisations. But a quick look at this list informs us of which terrorist groups were active in the decade prior to 1982.

They were: Fatah, ETA, the PLO, the Red Army Faction (Baader-Meinhoff), the Provisional IRA, the Red Brigades, the Japanese Red Army, the Ulster Defence Association, the FALN, ASALA, the Tamil Tigers and Hezbollah. Of these 13, only three can be said to have any association with Islamism. So it’s not likely that ‘terrorism’ in this period was conceived of as exclusively — or even mainly — Islamist in ideology.

The earlier history of the words ‘terrorist’ and ‘terrorism’ reveals other fascinating semantic shifts. Both words were first associated with the supporters of the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror — the terroristes in the revolutionary government were firmly state actors. Only after the 1860s was terrorism conceived as a non-state or anti-state affair. In 1946, The Annual Register refers to “the outrages committed by the Jewish terrorists in Palestine”, and a positive use of the word ‘terrorist’ even crops up in The Spectator in 1979:

In this enthralling autobiography the author of Maquis‥retravels the course of his life from his childhood to his war-time exploits as a terrorist in the Resistance.

To refer today to the French Resistance movement against Nazi occupation as a terrorist organisation would be met with justifiable outrage, such is the unbrigdeable distance between contemporary and historical usage.

What if the trend identified by Aly and Greenwald continues, and terrorism becomes synonymous with Islamist violence to the exclusion of all other meanings? Will circumstances demand a new label for politically motivated non-Islamist individuals and organisations? Or will the Breiviks of this world eventually prove too frightening and consistent to be dismissed as a-historical crazies and be brought back into the terrorist fold?

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.