The share market is not the real economy. It’s a parallel world, where image can be as important as substance, where sentiment carries as much weight as facts. If not more.

The freefall on the ASX, readily joining in overseas markets, says little about the fundamentals of the local economy — that much is clear from how miners have been punished as much as everyone else.

And the reality gap between the antics in the markets (where panicking fund managers are trying to protect the bonuses first and not their clients returns) and the real economy is just as stark as the dramatic pictures yesterday and this morning from London and other British cities. The rioting and flames tell us more about the problems in an economically-squeezed, austere British economy and society than do the sharp falls in the Footsie on the London Stock Exchange. There’s a feeling that all the public fury about the bailout of the banks and continuing fat cat salaries for bankers and others in “The City” has spilled over into an orgy of senseless rioting and looting that makes the ructions in Latin economies look like models of order and respect for the law.

That’s something we should keep in mind in Australia over the next few weeks: the crippling price falls for shares and other assets bear no resemblance to the reality of how the local economy is placed. There’s a saying in finance that the lessons of the past are quickly forgotten and so it is in the markets at the moment with the same crop of investors, managers and others fretting about the future in a way that proved to be unnecessary in the months after the GFC in 2008.

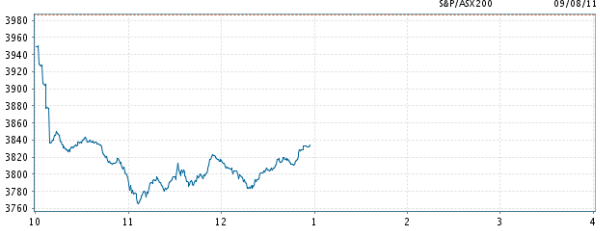

The S&P/ASX 200 performance from 10am until 1pm today

What’s notable this time is that, except for the odd screamer and Hanrahan, local commentary so far has been moderate and informed. One or two have raised the old bogey of housing prices, debt and inflation policies, but so far there’s no repeat of the Henny Penny commentary that we increasingly saw from late 2007 onwards.

But the lesson from the GFC is that sentiment counts — market sentiment, and consumer sentiment. It’s not just traders and bankers that demonstrate the herd mentality — we’re all less the rational creatures of economic theory than complex psychological machines capable of talking ourselves into, or out of, any mess. Australia’s successful response to the GFC hinged on the ability of the Rudd government to convince consumers that our banks were safe, and that it was determined to support employment — to which end it handed out money and told people it was their patriotic duty to spend it.

Consumer sentiment, which had been infected by the panic engulfing the world financial system, rallied in response and put a floor under demand. Hundreds of thousands of jobs were saved.

The risk now is that already flat consumer sentiment will again be a vector for the transmission of the panic in the markets into the real economy, despite the comparative strength of the Australian economy which just days ago seemed on the cusp of another rate rise.

And the risk is exacerbated by a government that is in a weaker position to respond to prop up consumer sentiment. Not weaker in the fiscal sense — as the IMF noted on the weekend, while there is no budget surplus to now draw on, our level of debt is low enough to comfortably absorb further deficits — but in a political sense. This government has none of the authority, popularity or trust that Kevin Rudd did in 2008 and 2009: consumers took heart from a rapid, assured response to the GFC by the government.

Julia Gillard would have considerable difficulty working the same magic now, even if the opposition were to abandon its reflexive negativity and put the national interest ahead of its own excitement at being so close to returning to power. Rudd himself lies in a hospital bed in Brisbane, remote from the action in his Foreign Affairs post. And the absence of Lindsay Tanner, in particular, now seems a bigger hole than ever in the Labor frontbench.

Labor now faces the real prospect of being mugged by a global economic crisis not once but twice. It is clear the US and European economies will stagnate for the rest of this government’s term and, probably, most of the following one as well. Any faltering of growth in China will require a wholesale revision of our economic prospects. Labor’s second term strategy was to bed down some hard reforms early and then benefit from the recovery as it neared the 2013 election. That strategy will increasingly look like a Pollyannaish scenario if consumers start to take fright.

Labor can curse its luck that John Howard got years of global growth while it had to cope with major crises, but it seems Gillard and Wayne Swan now have to step up and again battle the strange psychology of markets and consumers. For everyone — analysts, commentators, politicians and most of all consumers — it’s time to keep our heads.

Thanx for this balance to the chicken little stuff in the mainstream media.

Thankfully Mr Abbott is OS otherwise he would have talked the market down even more.

It is clear the US and European economies will stagnate for the rest of this government’s term …

Therefore it is also clear that China faces serious problems with its market (US + Europe).

Is it really that unclear how this will affect Australia? Just how would an Australian recession affect our jobs and house prices? Just how would house prices affect banks? Just how safe are our banks given that they rely on foreign loans to support our ponzi house price scheme?

I know its different here and the deflating house prices seen in other parts of the world can’t happen here because we are different. Thank god for those kangaroos.

@The_roth

On the contrary, shadow treasurer Hockey was on tv last nite saying that Australia’s economy is fundamentally sound. Is the Opposition more responsible and rational when not led by Abbott?

To me the panic is summed up by 2 things, the fall in the Australian dollar against the US because the US dollar is a “safe haven” despite the fact that it was the downgrading of the US credit rating that started all this and the fall in Australian mining stocks despite the fall in the US dollar and the massive rise in gold price.

Both of these defy logic and seem to bear out BK’ assetion that “fund managers are trying to protect the bonuses first and not their clients returns”