The calls for IR deregulation grow stronger by the day. It may not quite be a “tsunami of consensus”, as the AMMA claimed yesterday, in an unfortunate choice of words from its flacks. Nor is there, necessarily, a “revolt” in support of it, as per the home of reflexive calls for IR reform, the Financial Review.

The country’s richest and most powerful corporate elites pushing to impose poorer workplace conditions on people doesn’t quite fit the image of a plucky band of rebels, hoping against hope they can overthrow a repressive regime.

But the insistence on a link between Australia’s poor productivity and the Fair Work Australia framework continues to be made by employer groups and repeated without any attempt at analysis by journalists. And note, by the way, the inherent scepticism that (correctly) greets claims by unions regarding IR, whereas the claims of employers are given uncritical, front-page treatment.

While the link continues to be made, it behoves me to bore readers by repeating the salient work of the Grattan Institute, which has looked at productivity of late and tried to assess labour productivity, most recently with this paper by Saul Eslake. Eslake’s not exactly a raging lefty on the issue — he suggests there may indeed be some scope for productivity benefits from some form of workplace deregulation.

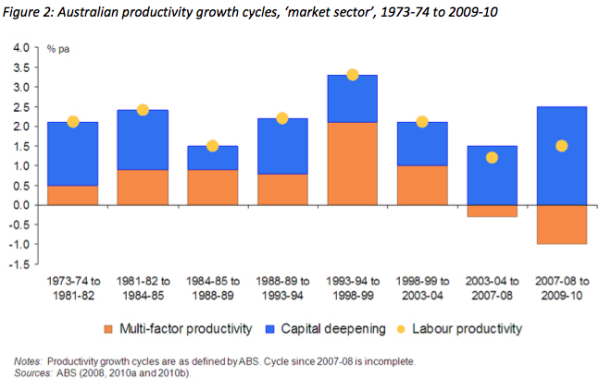

But a salient graph on the history of labour productivity via “productivity cycles” suggests the last round of IR deregulation, WorkChoices (which Eslake suggests wasn’t “productivity-enhancing”), had less than spectacular results.

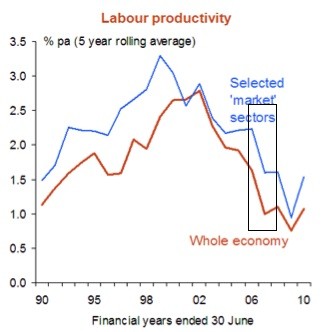

That is, the productivity “cycle” that included WorkChoices was the worst since the Whitlam/Fraser years — which, incidentally, saw much higher labour productivity than in the latter years of the Howard government. And in case you think it had nothing to do with WorkChoices, here’s another graph from Eslake’s paper, similar to one I’ve used before, where I’ve added a box to show the period encompassed by the operation of WorkChoices.

So when Don Argus seriously claims that “productivity has been woeful under Labor” as he allegedly did yesterday to a mining conference, he either can’t read simple statistics or he’s deliberately omitting the fact that it was even worse under the Coalition. Neither is particularly becoming from a man alleged to be an esteemed business leader.

Still, we only had WorkChoices for two years. If only there was a longer-term data set to draw on to get a proper, long-term perspective on the impact of IR deregulation. Well, Eslake provides that too, because it has some international data for comparison, including productivity data from New Zealand.

The Kiwis went even further than WorkChoices in 1991 with the National government’s Employment Contracts Act that abolished the award system and launched a ferocious attack on trade unions. Its excesses were reversed by Labour government’s Employment Relations Act in 2000, although the New Zealand IR framework is still less regulated than our own. Eslake uses OECD figures to look at productivity growth across several countries since 1990. In New Zealand, labour productivity grew by 1.3% pa under the Employment Contracts Act and 1.1% under the Employment Relations Act.

That sounds like a small difference but data from New Zealand treasury suggests the difference is greater. A NZ treasury paper that looks at labour productivity across growth cycles shows that from 1990-97, labour productivity grew at 2.5% per annum and 2.8% per annum from 1997-2000. But after 2000, it grew at only 1.1%, a big fall from the 1990s. So, evidence that IR deregulation boosts productivity, then?

Except, the fly in the ointment is, labour productivity in New Zealand grew even faster before the Nationals ripped workers’ rights away — at 2.9% from 1985-90. IR deregulation seems to have undermined productivity growth when it was introduced in New Zealand, like WorkChoices here.

Could it be that the level of IR regulation isn’t actually the determining factor in labour productivity that we’re being told it is?

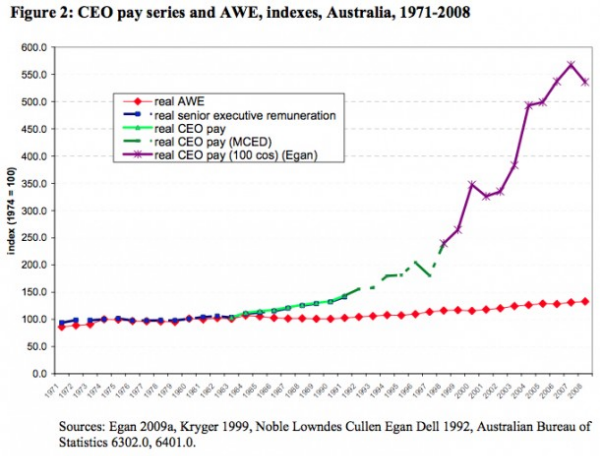

One more graph. When the Productivity Commission investigated executive remuneration a couple of years ago, it tried to get to grips with just how rapidly CEO and director remuneration had increased in recent decades. Griffith University’s David Peetz had a go at pulling together several series of data.

The PC had some quibbles about the “Peetz Index” and suggested it might have overstated remuneration growth slightly, but nonetheless included it in the section of their final report on remuneration trends. In his submission, Peetz compared average weekly earnings with executive remuneration.

The result should give pause to anyone who thinks the Heather Ridouts and Don Arguses of the world can lecture the rest of us about the need for lower wages and worse conditions.

could some one please do a study on the benefits to shareholders if the executives of Australia’s companies took a 10% pay cut. Let’s restrict it to anybody earning a base salary of say $200,000 so we’re not taking the bread out of anyone’s mouth. Or perhaps we could see what would happen if private sector ‘hospitality’ (in my line of work it would be corruption but seems if I’m a private sector exec no excess is too excessive) were stopped. Or perhaps the ATO could increase productivity by saying that a top of the line BMW was not an appropriate business expense?

Like the old men who send young men to war, sauce for the goose always seems less attractive when applied to the gander.

Decreasing workers rights and remuneration does not make them work harder, quite the opposite.

Also on a side note, to those who have been predicting a “double dip recession” (TTH et el) not only have you not had the first dip 4 years ago you now have missed out on the second dip with positive growth figures out today (largely caused by increased household spending). Looks like you just can’t catch a break.

.

TTH and his ilk can’t stand it when Australia does well.

As for that $500, perhaps he should just donate it to the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre. I’d call that a win-win.

In addition to the fine analysis in the article, why is insn’t anyone – including Crikey – catching Heather Ridout out in her patently false claims about FWA killing jobs by increasing shift loadings?

On Mon in The Age, and on Tuesday in the Oz, Ridout was allowed to claim that a glass manufacturing plant was not running an afternoon shift, and instead importing glass, due to the Modern Award increasing the shift loading from 15% to 50%.

This is just wrong. Anyone with a couple of brain cells and a computer can check on the FWA website and see that the afternoon shift loading remains at 15%, and then ask themselves why Ridout and the AiG are choosing to make such outrageously false claims?