It can be tricky for an opposition when the gods of economic data smile on a government, as they did yesterday in handing Wayne Swan a return to the low-inflation environment of 2010.

Andrew Robb, filling in for a travelling Joe Hockey, made the best of things with a sober press release warning that the low number “highlighted the softness in our economy”. “The softening inflation data gives the RBA something to seriously consider when it meets on Melbourne Cup day.” He also mentioned the impact of the carbon pricing package. All fair enough — the Coalition line is either that inflation is high, and therefore it’s no time for a carbon tax, or as Robb said, inflation is low, and therefore it’s no time for a carbon tax.

Bruce Billson didn’t quite see it the same way. In a press release late yesterday afternoon titled “Cost of living soars even before carbon tax”, he said “the latest Consumer Price Index (CPI) figures show Australian individuals, families and small business are being hit hard with the cost of living sky-rocketing.” No “softening” in sight. Billson was referring to the utilities costs which rose in the September quarter, courtesy of a round of price rises from state-owned electricity and water companies in July (tsk tsk, those pesky Liberal state governments). The ABS, in a new initiative, yesterday released a “seasonally adjusted” CPI figure yesterday that smoothed out such regular increases as electricity price hikes. The result was an even lower figure, 0.4%, which is getting into deflation territory.

I asked Billson’s media adviser, the estimable Kane Silom (ex-Steve Fielding) to explain the discrepancy between Robb’s “softening” and Billson’s “skyrocketing”, and he pointed to the rising cost of water and electricity as “essentials” compared to the cost of “luxury” goods, which had come down. It seemed an odd argument to make, given the cost of international travel had gone up while healthcare, milk, petrol, fruit and vegetables and housing costs all fell during the quarter, but anyway, no biggie. Utilities prices indeed went up.

We’ll leave aside the fact that groups such as the Energy Suppliers Association have said the Coalition’s threat to repeal the carbon pricing package will increase electricity costs — that’s not Billson’s portfolio. But his lament about electricity price rises seemed a little odd given a release he issued on the weekend. “Dodgy carbon tax modelling to hurt small business,” he warned, attacking “the government’s plan to fine small business for lifting their prices more than 0.7% under its carbon tax price gouging regulations”, which was justified by nothing more than Labor self-interest. “How there can be this decree that anything above a 0.7% price rise is gouging is ridiculous.”

Now, you’ll recall the opposition’s attempt earlier this year to confect “carbon cops” as the next big threat to our civil liberties, which turned out to be based on amendments to legislation backed by the Coalition itself last year. But the tenor of Billson’s weekend release was that the 0.7% cap on carbon price-derived price rises was too low and thus unfair on business. So, Billson complains about businesses not being able to lift their prices significantly on Sunday, and complains about businesses lifting their prices significantly on Wednesday. Moreover, impressively, both are the fault of the government.

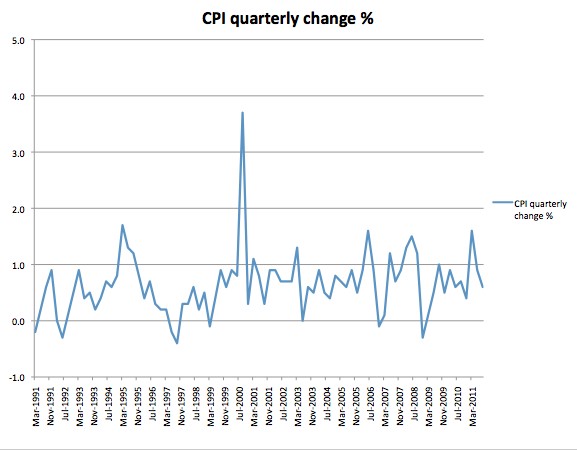

To put our inflation performance in context, this is the headline quarterly CPI change since 1991.

Wayne Swan’s inflation performance in a period of strong jobs growth since the GFC has been the same as, and if anything slightly better than, Peter Costello’s in the last five years of the Howard government. Swan and Costello had different challenges — Costello had a booming economy and a prime minister obsessed with spending his way to electoral success. Swan had to pump-prime the economy in the face of the GFC, then taper the stimulus off without over- or under-cooking the economy. Both did a reasonable job.

Indeed, the longer-term story is, ever since the early 1990s recession crunched inflation out of the economy — along with a generation of workers — policy makers and the Reserve Bank have been pretty successful at managing inflation, whatever critics might say.

With such mixed signals coming from the same side of politics, just days apart… it is a wonder anyone believes anything anymore. And yet despite that, the loyalists to the conservatives hang on every contradictory word that comes from that broad side, (and the same is probably true of those loyalists on the other side!)

I still wanna know what good conservative caring people think about Mr Abbott and his plans to scrap the Poker machine reforms that are soon to come in. He is sacrificing families for big money. He is ignoring thousands of really troubled families, for the approval of the gaming industry…. come on you conservative devotees out there… justify that one …. (I know this is off topic… but there is no article on it specifically….)

Good conservative voters (and their families) all know that those people troubled by pokies are all godless dole bludging lefties.

That particular camp knows that when conservative politicians talk about families, they are talking about “good” families… their families.

These families will only be negatively affected by mandatory recommitment because it will mean acrylic (instead of polyester) uniforms for the local footy club, more expensive meals at the club bistro, and less golf for dad….

Morgan… you are probably right. “its their own fault” sort of argument. “I dont have a problem in that area, … they should not either.” yep… heard that all before!

Massive money printing equals lower inflation? Don’t think so, I smell massive manipulation of the figures. But then, why should Oz be any different from any other country?