After years of neglect the federal government has shovelled billions of dollars into the mental healthcare system — but the debate on how best to spend it has just begun. In the first of a four-part joint investigation with Inside Story, health journalist and Croakey blogger Melissa Sweet surveys the long and often bitter road towards real reform …

Before we dive into the murky, tumultuous waters of the present-day debate about mental health, it’s worth pausing for a quick trip back in time. Our destination is Roma, in the Darling Downs of southern Queensland, almost 30 years ago.

At the local hospital, a long search is ending in a bittersweet meeting. An idealistic young woman called Dawn O’Neil has tracked down a woman she had long thought dead — her father’s mother — who has been resident at the hospital for many years. Julia Mant was moved to Roma after a Brisbane asylum closed. She had been admitted to institutional care when she became unwell after the birth of one of her children. As so often happened, her family connections had been lost, no doubt reflecting the shame and stigma surrounding mental illness.

O’Neil had grown up believing her grandmother was dead, and only discovered otherwise when she met an aunt in the United States in the early 1980s. “My grandmother had spent her whole adult life after the birth of her third child in various asylums, and the family didn’t want to know her. They wrote her off,” says O’Neil. “My dad was told when he was little, when he was naughty, that ‘you’re mad like your mother’. Now, on reflection, I can see that my own father had a mental illness that was never diagnosed.”

By the time O’Neil found her grandmother, decades of institutional living had left their mark. There was no chance of rehabilitating her into the community, and she died just a few years later. Her grandmother’s history became part of O’Neill’s career choices, though, and she set about striving to improve community understanding and responses to mental health.

Through her work over more than 15 years with Lifeline, beyondblue, the Mental Health Council of Australia and other groups, O’Neil has developed a keen understanding of the complexities of mental health reform. She also has a broad perspective on the interests at play in the current acrimonious debates about reforms announced in the May federal budget.

While a five-year commitment of $2.2 billion was seen as a significant win for the sector in tight financial times, praise for the package quickly dissipated, and since then there have been more negative than positive headlines. The concerns largely centre on cuts to GP rebates and a reduction in sessions funded under the Better Access program, which provides referrals from GPs to psychologists and other health professionals under Medicare (about a quarter of the budget’s mental health package was funded by Better Access savings.) Some critics have also questioned the expansion of the youth mental health service, headspace, and programs for early intervention in psychosis.

Other elements of the budget — accommodation and employment initiatives, new support measures for people with severe mental illness, more funding for carer respite services and funds for a 10-year Roadmap for Mental Health Reform — have received far less attention. Indeed, one of the least remarked elements of the budget is potentially the most exciting: support for developing online treatments for depression, anxiety and related disorders.

O’Neil believes much of the post-budget critique is being driven by professional self-interest, but says the contretemps needs to be seen in the context of sweeping changes in mental health in recent decades. It is easy to lose sight of the fact the federal government was perceived to have no role in mental health until about 20 years ago — that it was seen as strictly states’ business.

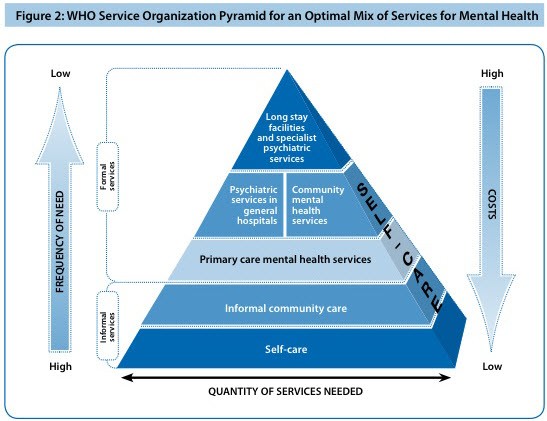

O’Neil refers to a 2009 World Health Organisation report, Improving Health Systems and Services for Mental Health, which includes a deceptively simple diagram showing the optimal mix of services in the shape of a pyramid. At the pointy end are long-stay and specialist psychiatric services, the most expensive type of services. At the bottom are informal community care and self-care, the least expensive but most widely needed. In the middle are psychiatric services in general hospitals, community mental health services and primary care mental health services.

With Australia continuing to spend a large chunk in the pointy end, the diagram represents a tremendous challenge to current practices.

“We’re slowly unpicking that and trying to turn the whole thing on its head,” says O’Neil. “That’s a big change. There are a lot of people who built their careers and their reputations on doing that acute end very well. For many of them, this other paradigm threatens their income, their livelihood, their nice lifestyle.”

O’Neil presents a big picture view of mental health reform that has many resonances for health reform more generally — the need to reorient complex systems in the face of a mire of resistance from professional, bureaucratic and institutional interests. Another view of the post-budget bunfights comes from health policy analyst Jennifer Doggett, who observes: “It’s partly just a function of what happens when you get a win. It’s like when a patriarch dies, and the will is read, and everyone starts squabbling.”

Given the size of the Better Access industry — the program is worth around $10 million a week in government funding to psychologists, GPs and other health professionals (and that’s not including patient co-payments, which are often significant) — the squabbles are not surprising. Indeed, the recent Senate inquiry into the budget reforms revealed some rather poisonous divisions between registered and clinical psychologists over whether there should be differential rates for their services under Better Access. Psychologists who made submissions to the inquiry faced threats and intimidation from colleagues, including incitements to report them for ethical breaches.

The inquiry report noted: “The committee wishes to place on record that the actions of numerous parties within the psychology profession caused considerable frustration for the committee, anxiety for submitters, and reflected poorly on most of the professional bodies involved.”

*Tomorrow: Unpicking the backlash against psychiatrists Ian Hickie and Patrick McGorry …

**Declarations: The Croakey health blog, which Melissa Sweet moderates, has received funding from the Brain and Mind Research Institute and the Public Health Association of Australia. The author has also been paid for research (not related to mental health) through the University of Melbourne centre involved in the Better Access evaluation, and the lead author of the evaluation, Jane Pirkis, was interviewed for this article.

I have been a Registered Nurse in Mental health in South Australia for more than 20 years. Interest groups in mental health have always been asking for money and they get a lots of sympathy from good hearted folks. Now there is money is flowing in. I would argue that one of the unforeseen consequences of all this money flowing in is a lessening of mental health staff who are working at the ‘coalface’ of mental health and a vast increase in the number of people who are seconded from working with patients (or actually running wards and units) to ‘special projects’ that remove them from patient care. State bureaucracies should do surveys of the number of mental health staff who are actually removed from actual patient care. Most of the ‘special projects’ I have encountered in mental health have dubious value.

The pyramid needs a review… We should have less clients in hospital and more in community health and primary care! Until we increase spending in mental health promotion, we will continue to have the pointy end over represented. Early intervention care is important…but it is too little too late. Mental health promotion and the expertise of mental health nurses needs to be better supported in mental health budgets. For too long we have looked through the lens of psychiatry (medical models) to solve a mental HEALTH problems. It is time to use health models to solve health problems! Time to get mental health nurses more involved, because health promotion, health and well being is their core buisness. Let’s start to match the health problems more strategically with the disciplines that are more likely to be able to solve the problems.

The only losers will continue to be the sick. It is happening now in all areas of health care. Skilled lobbying and splintering of the groups who can most help. Getting rid of the most experienced professionals, discrediting practices and individuals and “turning the pyramid upside down” has not helped any public health system; and there is no evidence it will help the mental health system either. No one sector owns the health budget, and there is no one answer that will solve the problem. Until all the parties sort out their issues, the sick are better off without us.

We will all be victims if the NSW and Victoria’s conservative governments plans to privatise nursing systems and ambulance services and the privatisation of all hospital services comes to fruition. Then the sick will have no where to go as well as no one to look after them.

Psychiatry needs to get over their egos and their arrogance and realize they’re not the answer on their own, they need to work side by side with psychologists and nutritionists, not one without the other, to keep them honest, and provide better care.

They also need to stop telling troubled victims and their families that they are stupid, or have no insight, or have anosognosia, when the victim and their family are telling them they’re poison is making them sick, its just so wrong.

As if people don’t know what makes them sick, they know and knew alcohol and drugs are and were no good for them, its in the news all the time, in print, radio, we are taught that all our life, and yet mental health do the opposite when it all boils down to it with their drug poisons, that they sell in the same way drug dealers and breweries do.

And get rid of the word Mental for a starter, try emotional health, psychological health, mood health, attitudinal health, anything but Mental.