Over at AASNet (the Australian Anthropological Society web discussion group) a recent thread that dragged a hangnail across the raw ethical and professional nerves of many anthropologists caught my attention.

This thread raised issues of particular relevance for those anthropologists that provide consultancy services – particularly those working on mining and major development projects – rather than those that work for a single agency or company.

Somewhere in that thread I found the following article written by Dr Barbara Dobson and Ken Macintyre – both anthropologists that have worked in this field for many years – that looks at these issues generally and also in the light cast by recent events in the west.

Barbara and Kenneth note that:

From our experience, mining companies rely on the anthropologist’s advice on issues of indigenous heritage and Native Title.

No anthropologist is coerced into unethical situations or practices. They have a choice.

They either do so willingly or they do not take on the job.

What follows is a lightly edited version of their paper which I present here as a guest post.

The Yindjibarndi documentary & issues relating to consulting anthropologists

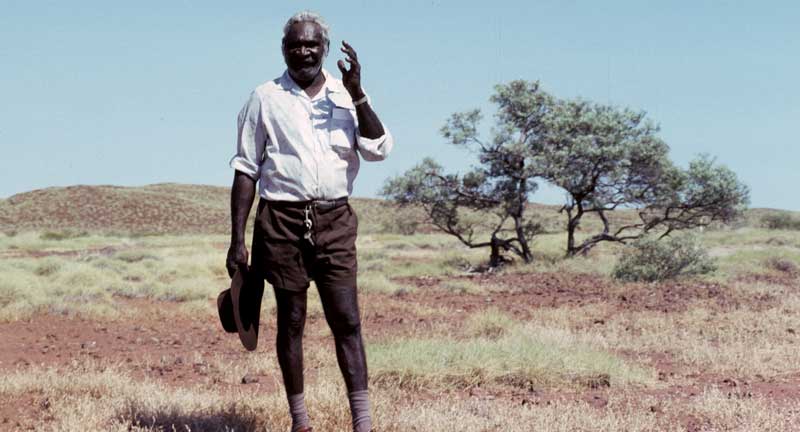

Congratulations to the Yindjibarndi Traditional Owners on their documentary which exposes a company’s bullying tactics over access to indigenous land and cultural heritage.

This documentary will hopefully generate further discussion on the role of anthropologists vis-a-vis mining and development with a view to the real world of consultancy anthropology.

The way we see it is that the role of a consulting anthropologist is one of research, recording and facilitating Aboriginal consultations.

It is fundamentally the role of a field secretary who is aware of the socio-political and cultural context in which they are working.

The anthropologist records the events and discussions taking place between indigenous people and the proponent in a non-prejudicial manner, and when facilitating meetings, the anthropologist must include the relevant recognised heritage spokespersons and Native Title representatives who speak for the particular Project Area under consideration, and they must ensure that the Elders/ Native Title Claimants/Holders are free to ask questions of the company and to have their say on any issues of concern to them.

The anthropologist should not in any way influence the outcome of these meetings, no matter who their client is.

The question of who pays the anthropologist shouldn’t matter; whether it is a mining company or an Aboriginal organisation, the results should be nonpartisan.

Sadly, too often highly qualified anthropologists perceive themselves as ”fixers’ for a wide array of mining or development-related issues and they do not hesitate to manipulate local Aboriginal politics and take advantage of indigenous poverty by offering handfuls of cash to achieve company ends.

There is always the potential for a conflict of interest between the anthropologist’s professional or personal code of ethics and the mining company’s way of achieving their economic objectives.

In discussing all this we should get away from the noble idea of anthropology and get down to the nitty-gritty of Anthropolitics – because that’s what it’s all about.

The Yindjibarndi documentary says it all.

A white mining company wants to access mineral resources on the cheap.

It comes up against a formidable Aboriginal group such as the Yindjibarndi who understand the Company’s exploitative tactics and who stand up for their rights as Native Title Claimants.

Prior to the meeting the Company knew that in order to get its approvals through it would have to go through the motions of a democratic voting process or rather pseudo-democratic voting process.

In consultation with their anthropological advisor and legal expert, arrangements were made to bus the dissident group to the meeting, thereby stacking the votes in favour of the Company’s agenda.

A tried and true tactic which never fails – unless of course it is captured on film and carried into cyberspace for the whole world to see, as in this case.

The strategy of bussing people around is not new. It was used effectively during the Swan Brewery protest in Perth where Aboriginal dissidents were ferried in from Wiluna to speak against local Nyoongar Elders who were trying to protect their spiritual heritage from development. The Wiluna people were not related to the Swan River Nyoongars but this didn’t matter to the politicians.

The development still went through.

Behind all of these tactics, there is an economic or political motive which is to divide and dominate. Indigenous poverty facilitates this behaviour.

There is also the ever-present inter-group indigenous factionalism and jealousy which fuels such actions.

However, without the white agents such as the anthropological advisor and lawyer to approve, orchestrate and mobilise the dissident group, and the Company to fund it all, none of this would take place.

It’s a question of ethics and no matter how much professional accreditation one has (or doesn’t have), it all comes back to the anthropologist’s own ethical and moral conscience.

It is well-known that if an anthropologist does not come up to company standards and does not get the desired results, he or she can be easily removed and replaced by another anthropologist who will comply.

There are high expectations and pressures placed on company-employed anthropologists to assist in furthering and fulfilling company objectives.

It is difficult for an anthropologist not to comply with company objectives because this can mean loss of contract, and loss of employment (present and future) not only with this company but with others for word-of-mouth travels fast in the mining industry where anthropologists are soon branded as either ‘good’ or ‘bad.’

This labelling has nothing to do with professional anthropological accreditation but rather how successfully an individual complies with achieving the company’s goals.

A “good” anthropologist gets the company its desired outcome;’ a “bad” one doesn’t. There is a lot of money at stake and anthropologists come cheaply in the scale of things.

What some anthropologists are doing today in manipulating Aboriginal groups against another in order to achieve Company ends is not only unethical but potentially very dangerous.

It is only a matter of time before someone is seriously injured or even murdered as a result of family disputes over Native Title or sacred sites brought on by white anthropologists and lawyers manipulating potentially lethal variables.

We have experienced firsthand attempts by company-hired anthropologists to solve things politically for their client by bringing in dissident groups to speak against local Native Title Claimants who are trying to protect their heritage sites.

This strategy only exacerbates and widens the conflict between groups whose relations are often already strained.

Once again we congratulate the Yindjibarndi Aboriginal Corporation for standing up for their rights and exposing exploitation and unfair dealings which too often go unreported.

We would recommend that the Yindjibarndi documentary be made compulsory viewing for Applied Anthropology courses ( especially for those students intending to become consultant anthropologists) so as to give them a realistic insight into ‘on-the-ground’ complexities and manipulations that occur in the real world of anthropolitics.

++++++++++++++++++++++++

For some more background on these issues see this recent letter from a firm that had been engaged to do heritage survey work for one company in the west and also this post that raises concerns about site damage on Yindjinarndi lands.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.