“Australian exceptionalism” … let that phrase roll off your tongue. Now stop laughing for a moment if you can.

There’s something about that phrase that just doesn’t sit right with us. We’re not only unaccustomed to thinking about ourselves that way, but for many it’s a concept that is one part distasteful to three parts utterly ridiculous — try mentioning it in polite company some time. Bring a helmet.

We’ll often laugh at the cognitive dissonance displayed by our American cousins when they start banging on about American exceptionalism — waxing lyrical about the assumed ascendancy of their national exploits while they’re forced to take out a second mortgage to pay for a run-of-the-mill medical procedure. That talk of exceptionalism has become little more than an exceptional disregard for the truth of their own comparative circumstances.

But in truth, we both share that common ignorance — we share a common state of denial about the hard realities of our own accomplishments compared to those of the rest of the world. While the Americans so often manifest it as a belief that they and they alone are the global benchmark for all human achievement, we simply refuse to acknowledge our own affluence and privilege — denialists of own hard-won triumphs, often hysterically so.

Never before has there been a nation so completely oblivious to not just their own successes, but the sheer enormity of them, than Australia today.

In some respects, we have a long-standing cultural disposition towards playing down any national accomplishment not achieved on a sporting field — one of the more bizarre national psychopathologies in the global pantheon of odd cultural behaviours — but to such an extreme have we taken this, we are no longer capable of seeing an honest reflection of ourselves in the mirror.

We see instead a distorted, self-absorbed cliché of ourselves bordering on parody — struggling victims of tough social and economic circumstances that are not just entirely fictional, but comically separated from the reality of the world around us.

So preoccupied have we become with our own imagined hardships, so oblivious are we to the reality of our privileged circumstances, that when households earning more than $150,000 a year complain about having government welfare payments scaled back, many of us treat it as a legitimate grievance.

Somewhere along the highway to prosperity — and an eight-lane highway it has been — far too many of us somehow managed to confuse cost of lifestyle with cost of living. We managed to confuse government assistance as a means to enable the less well off to achieve a better standard of living and greater opportunity, with government assistance being a God-given right to fund the self indulgences of aspirational lifestyle choice beyond our income means. Too many of us have demanded our dreams be handed to us on a plate, and if our income couldn’t provide for them, we demanded that government should give us handouts to make up the difference.

So let us take a hard look at our economic reality.

Over the medium term, our broader economic performance has been nothing short of astonishing. Before the resources boom was even a twinkle in the eye of Chinese poverty alleviation, our performance was world beating — that is worth keeping in your thought orbit. Big Dirt has a bad habit of propagandising about its own contributions and the Australian public has a bad habit of believing it when it comes to our own national development of late.

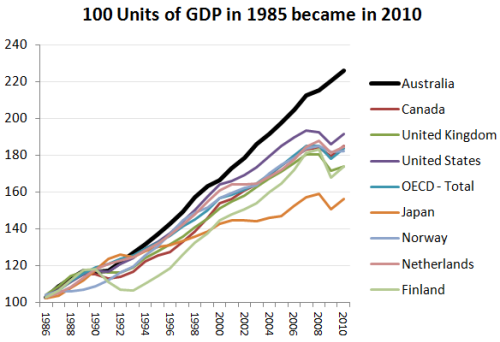

Imagine if, in 1985, all OECD economies had exactly 100 units of GDP each. If we then tracked the growth of that GDP (using OECD data) over time with the actual growth rates achieved during that period (creating a basic index) this is how economies changed:

Only Turkey, Israel, Ireland and Korea have experienced more growth — with Turkey and Korea pursuing the change from developing to developed status, Israel partially so as well and Ireland recovering from the economic lethargy of civil war, we are the highest growing country that can be remotely called a developed country with no unusual circumstances. Putting this into context, let’s trace that growth over the last 25 odd years with some of the countries we are often compared to.

It’s kind of mind blowing — we grew faster, significantly faster, than all of the countries we are usually compared to, including over the period before the resources boom. But you ain’t seen nothing yet …

Crikey encourages robust conversations on our website. However, we’re a small team, so sometimes we have to reluctantly turn comments off due to legal risk. Thanks for your understanding and in the meantime, have a read of our moderation guidelines.