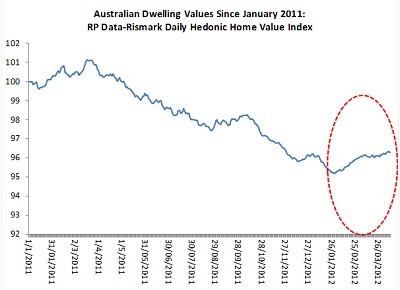

Looking at RP Data-Rismark’s daily hedonic home value index, which is also published by the Australian Stock Exchange, we can see the “stabilisation” evident in Australia’s housing market in 2012 has galvanised further during the month of April.

Australian home values are now in the black for the first time in 2012, having fully recovered from the drop recorded during the seasonally weak month of January. At April 10, home values across the eight capital cities had risen by 0.3% above their end 2011 levels:

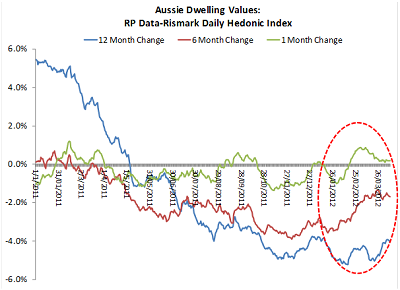

The improvement in housing conditions can also be viewed through the rolling one-month, six-month and 12-month returns, which simply reflect the raw capital growth, exclusive of any rents, realised over the period in question.

My second chart illustrates that analysis. While year-on-year returns (blue line) have flat-lined at around -4%, we can see more clearly the effect of the recent house price growth on the six-monthly (red line) and monthly returns (green line), which are heading towards or are above the horizontal x-axis that denotes zero growth:

One key takeaway from the chart above is that the month-on-month change in Aussie home values has been positive since February and remains in the black as we head into the second half of April.

The crucial question is what will happen in the remainder of the year. In late 2011 I forecast Australian home values would stop falling in the first quarter of 2012 and we would possibly see a return to capital growth, which is the way it has panned out.

The good news for housing investors is that the financial markets are putting a near certain (or close to 100%) probability on a third RBA rate cut in May — and some think we might get another in June. As regular readers would know, I did not expect the bank to cut rates last month — or in the preceding two months — given that I deduced that they would want to wait until they got the all-important ABS inflation data at the end of April. The RBA is fond of establishing subtle decision-rules or offering guidance on the future direction of policy if inflation, employment and growth behave in certain ways.

After its uneventful April meeting the RBA clearly communicated that it would trim rates in May if it got a weak inflation read for the first quarter of 2012. Analysts have subsequently inferred that to mean the RBA will cut rates if core or underlying inflation prints at less than or equal to 0.6% — or under 2.5% annualised.

Yet the market seems to be overlooking the fact that the RBA will want to “look through” the volatile, and frequently revised, quarterly information, towards the six-monthly and yearly prints. So in that context a May rate cut will likely rely on the six- and 12-monthly outcomes being somewhere between 2.0% and 2.5% on an annualised basis. If they somehow come out in the top half of the RBA’s target 2-3% band it is hard to see how the central bank will relax rates barring further offshore disasters or a big jump in the jobless rate.

With the bank estimating that core inflation is right in the middle of its target band — albeit before the full effect of the November and December rate cuts — the core numbers would have to print very high in the first quarter of 2012, and/or the ABS would have to upwardly revise the remaining 2011 data in order for us to see an adverse result (given the advantage of being able to discard the high March 2011 number from the annual time-series).

With the above in mind I would not attach a 100% or even 90% probability to a rate cut in May. It is more than likely but will depend on the pulse of price pressures during the past 12 months.

Another thorny question for the RBA is what it would do if the year-on-year inflation data prints just below the mid-point of its target band but the six-monthly average is above it. The RBA might be swayed by the argument that with the Aussie dollar off 4-5% from its recent peaks the economy is already getting the benefit of some extra stimulation that is tantamount to half a rate cut.

The flipside of that currency depreciation is imported inflation as opposed to imported deflation, where the latter had been influential in keeping overall price pressures in check via low tradeables and goods price growth.

A final curveball is what the banks do with their margins. We have ANZ’s decision on Friday this week. If I was the CEO of a major bank I would definitely bump up lending rates by a good 5.0 to 7.5 basis points.

Why? First, because you will boost your net interest margins in an environment in which profits are going to be hard to come by due to structurally low credit growth — funding costs have been falling since January. A second reason to widen margins is to amplify pressure on the RBA to neutralise that change in lending rates in May.

All else being equal banks do better in low interest rate climates. Asset prices rise, credit growth accelerates and impairments decline. So the banks will want to see the RBA cutting in May and bumping up margins in April will increase the probability of that happening. Borrowers are still better off because the RBA ordinarily moves in 25 basis point increments.

A final reason to expand margins is simply because, as an oligopolist, you can! From a margin extraction point of view the banks need to break the back of the purported link between the RBA’s target cash rate and actual, economy-wide lending rates.

While the link will always exist in practice (i.e. notwithstanding what people may want you to believe), the banks should rationally want to improve their ability to freely profit maximise without annoying politicians and commentators interfering with their decision-making processes, as has been the case of late.

*Christopher Joye is a financial economist and director of Yellow Brick Road Funds Management and Rismark. This article — first published at Property Observer — is not investment advice.

I’d love to know the answer to the following, and so would many of my friends: Since our economy is strong, our debt is low, our banks are AAA and are guaranteed by the Government, why do we pay the highest home loan interest rates in the western world.

If UK banks can offer 3.99% (Halifax new SVR of 3.99%, 04/03/12) with all their problems, never mind the UK’s problems, why can’t our banks match that?

Our SVR (Westapc today 6.81%) is 71% higher!

Jed

Couple of reasons. RBA is happy with interest rate at long term average, they are afraid of inflation and don’t want to cut. The banks offer term deposits above 5% to attract customers so their funding cost is high, if they offer lower than that they can’t attract a lot of customers especially the super funds they will drift to more profitable investments.

UK banks seem to make profits taking deposits at 3%.

(http://www.interest-rates.org.uk/ukorder7.php) Today.

Given that property price comparisons do not actually involve like for like, it would be a careless man who looked at 3 months data and declared that the corner had been turned.

This game has a long way to go.

Why do we pay such a high price for our interest rates? Well, mainly because we aren’t in recession like the rest of the world, but also because our banks have huge exposures to the real estate market due to historical reasons, one being their oligopoly, and the fact that Australia is actually a huge risk for overseas lenders because of that.

We are still prone to a major drop/correction in house prices if the economy does go into a full blown recession. The banks will find themselves in serious difficulty in that scenario, and it won’t be the government’s fault that they are loaded to the hilt.