Update below

Australia is a high-cost place to do business, apparently.

I know because I read it in the papers regularly. Tom Albanese, of Rio Tinto, complained this week about the high cost of doing business in Australia. BG Group saying the cost of its Gladstone coal-seam gas project have blown out. The Business Council cited high costs back in April. One of those absurd “business roundtables” the AFR conducts, back in February, was given over to business executives lamenting “we’re becoming a high-cost, low-productivity nation”.

Usually the fault is laid at the blame of the government. Labor was “anti-business”, complained Graham Bradley in February, mainly because of the Fair Work Act. But the carbon tax cops criticism too. Today the head of the AIG complained that the carbon tax was creating uncertainty because, unlike the GST, businesses couldn’t calculate its impacts.

So let’s look at the evidence.

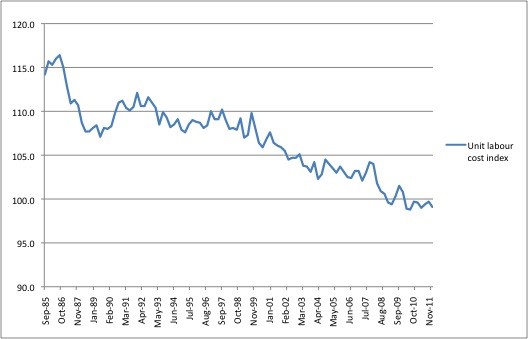

Has the Fair Work Act increased costs for business? Let’s look at the ABS’s unit labour cost index. When the index is above 100, wage pressures are assumed to exist. How has it fared under this government?

So, this is pretty much the only government in 30 years to eliminate wage pressures for business. The only area where the government has failed to curb wage pressures has been in executive remuneration, which continues to relentlessly increase at rates well ahead of inflation.

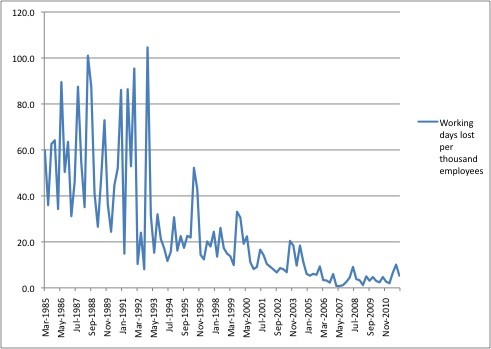

How about industrial disputes? Let’s have a look at the long-term trend. This is the number of days lost to industrial disputes per thousand employees. There was a much-vaunted spike in disputes in the September quarter last year, mostly driven by aggressive employers, but otherwise the level of disputes remains at historic lows.

What about the business cost that is in the direct control of government, tax? Last year’s budget papers tell us the ratio between company tax to corporate gross operating surplus:

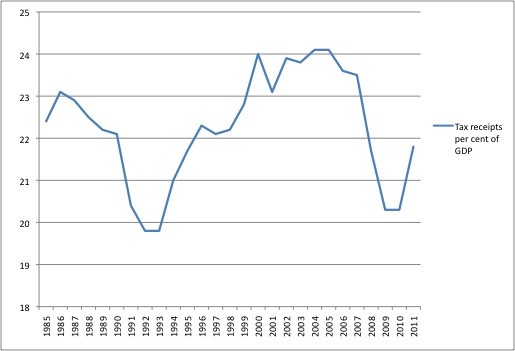

That is, outside mining, the overall tax take from business has fallen as a proportion of gross operating surplus. Plus, there’s the small matter of the corporate tax cut the government wants to introduce, which the Coalition and the Greens are opposing. In fact, this is a low-taxing government compared to its predecessor. Remember the Coalition’s rhetoric about being the party of small government, then have a look at tax revenue as a proportion of GDP and figure out which side of politics taxes less:

What else could the government be doing? Well it could avoid stimulating the rest of the economy so companies in the resources sector such as BG Group that need construction workers and material aren’t competing against the rest of the economy. And, lo and behold, the government is engaged in a massive fiscal contraction even before we get to the issue of a budget surplus for 2012-13.

What about the carbon price? Is that really a major source of uncertainty for business? Innex Willox of the AI Group laments that the impact of the carbon price is harder to calculate than the GST. But the carbon price impact will be small compared to that of the GST. Work done by the CSIRO and AECOM for the Climate Institute shows the price impact from the carbon price will be 0.6%, barely above the impact of Cyclone Yasi last year (0.5%), less than Cyclone Larry (0.8%) and less than a quarter of the impact of the GST (2.5%). Treasury’s assessment is that the impact will be 0.7%.

That’s the impact on consumers, not businesses, but it gives a clear idea of the scale of impact compared to the GST that Willox believes was so much easier.

The historical data suggests that, when it comes to labour and tax costs, the claim that Australia is becoming more expensive is dead wrong. In fact, it’s the reason why the wage share of national income is currently only just above its historic low of 52%, while the profit share is higher than at any time before 2008. And that’s why capital expenditure is at record levels — nearly 30% of GDP. The business decisions of investors contradicts the claim that we’re driving business away with high costs.

The issue is not so much whether Australian is becoming a more expensive place to do business, as whether Australian business will ever be satisfied or whether it will continue to push for ever more wage cuts and corporate tax cuts at the expense of the rest of us.

Update: The ACTU’s Matt Cowgill says I’ve misused unit labor costs – see comment 2. For a detailed treatment of the issue (esp. minimum wages) see pp.44-54 of the ACTU minimum wage submission linked to above (and here).

Gee if only some this rational fact based analysis hit the MSM!!

Excellent Mr K.

I await with enthusiasm the avalanche of complaints from these industry groups about the absurd wages being paid to these whining executives in Australia. Seems they get paid for making excuses and blaming everything but themselves.

This is a really good piece, but Keane has misunderstood the index of real unit labour costs (RULCs). RULCs are not like a confidence index or a PMI in which 100 (or 50) represents a balance between positive and negative movements.

Rather, RULCs represent the average labour cost of producing a unit of ouput, adjusted for inflation (using the GDP deflator). Because RULCs are presented in the National Accounts as index numbers, they need a base period. The index is set to equal 100 in the base period. The series could be re-based and set to equal 100 in any other period.

The level of the RULC index has no meaning. The RULC index is only used to show the rate (and direction) of change in labour costs.

Stable RULCs imply that the wages share of national income is stable, whereas falling RULCs imply a falling wages share*. If the real compensation of labour grows at the same pace as labour productivity, then both the wages share and RULCs will remain constant. The falling RULCs (and falling wages share) in the 2000s imply that the growth in the real compensation of labour has lagged behind productivity growth.

[*Note: RULCs are not exactly equivalent to the wages share, as RULCs use gross value added as a denominator, which is broader than the total factor income used as a denominator in wages share calculations. They are nevertheless close to equivalent.]

Taxes pay for an infrastructure and a health system, both of which are unavailable in many places where companies do business. In much of Africa, for instance, mining companies employ workers who are HIV positive, and have to provide (admittedly rudimentary) health care for them.

Thanx for this piece, and thanx to Matt Cowgill for clarifying index of real unit labour costs.

Good afternoon Peter. The right wing trolls seem to avoid pieces that report inconvenient truths, but should they emerge I look forward to reading you play Whac-A-Mole.