Public transport travel in Australia’s capital cities gets a massive, growing financial subsidy. Passengers don’t pay for any of the capital costs and on average only pay for around a third of operating costs. Yet despite of the subsidy, public transport accounts for only about 10% of all motorised trips.

The single largest group of beneficiaries are those who work in the CBD. They’re the main reason transport authorities have to provide enormous capacity to meet demand in the peaks. They don’t however tend to use public transport in the off-peak when there’s plenty of spare capacity — they prefer to drive.

A key question is why CBD workers — or any traveller who doesn’t qualify as disadvantaged — warrants such a massive subsidy.

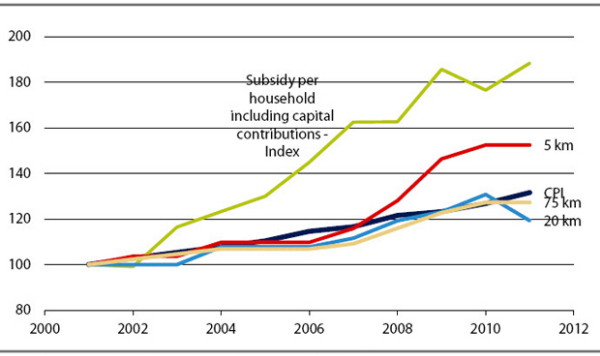

Index of subsidy per household and selected CityRail weekly tickets (including inflation). Source: IPART

One of the traditional justifications is equity. Yet most passengers aren’t on low incomes — indeed many are on quite good incomes. In fact most passengers aren’t even entitled to one of the many and varied concessions offered by transit authorities (not that even these necessarily indicate need — for example, in Victoria anyone aged 60 years or more is entitled to a generous Seniors concession, whether they’re working or not).

Other essential services like electricity, gas and water recover their full financial cost, both capital and operating, from customers. They target concessions to those who actually need them. Public transport, however, subsidises everyone who uses it irrespective of their means.

The irony is public transport isn’t actually very good at transporting those who really do rely on it. The key requirement of travellers who’re wholly dependent on public transport is for off-peak and cross suburban services (these are the 90% of motorised trips that everyone else uses cars for), yet what’s offered to them in Australian cities is of very poor quality.

And that’s primarily because governments chronically under-invest in public transport. It shouldn’t be a surprise of course, since governments have to provide all the capital and then fund an ongoing operating subsidy. For example, CityRail in NSW recovers none of the capital cost in fares and only 22% of operating costs.

Contrast this with major road projects. Many of the freeways constructed over the past 20 years in Australia’s capital cities were built and operated with private finance. The direct cost to government in terms of current outlays is small, so it’s no wonder they’ve historically favoured freeways at the expense of public transport.

The paradox is those who most need public transport suffer a grossly inadequate level of service in large part because public transport is so heavily subsidised. That subsidy is ostensibly intended to help them but arguably has the opposite effect. The main beneficiaries of subsidies are travellers who by any fair or reasonable measure don’t warrant it.

Another traditional justification for subsidising public transport is negative externalities, particularly traffic congestion and the environmental impact of cars. Neither of these hold up well to closer examination.

We already know new public transport projects do no more to mitigate traffic congestion than building new freeways do. Traffic congestion needs to be tackled by the combination of road pricing and more and better public transport services, but that doesn’t require it to be subsidised. All that matters is the relative price to the traveller of driving versus public transport.

The environmental justification is also weak because in many cases cars aren’t a substitute for public transport. The vast bulk of CBD travellers are “captive” to public transport — driving is not an option for them because the journey’s too far and the cost of parking is too high. And those who’re entirely dependent on public transport — like students, the handicapped and the poor — by definition don’t have the option of driving.

There’s also a “public goods” argument that mercifully is trotted out with decreasing frequency.

Crikey encourages robust conversations on our website. However, we’re a small team, so sometimes we have to reluctantly turn comments off due to legal risk. Thanks for your understanding and in the meantime, have a read of our moderation guidelines.