Yesterday we looked at the major economic challenges facing the country, with the goal of putting together a budget that addressed them, free of political self-interest.

Today we’ve had a go at putting together a series of budget measures aimed at addressing the issues of decarbonisation, housing supply, infrastructure provision and long-term fiscal stability. Let’s go through them.

1. Decarbonisation. As we noted yesterday, with a form of carbon pricing starting from July 1 and a major range of government “direct action” initiatives to support it being introduced, the primary problem we now have in the ask of reducing the Australian economy’s over-dependence on carbon compared to similar economies is the vast range of tax expenditures that encourage fossil fuel use, creating a policy push-me-pull-you that will negate the impact of a carbon price and associated measures.

In its budget submission, the Australian Conservation Foundation has costed the removal of a range of pro-fossil fuel tax concessions. We’ve adopted two of their proposals — removing the diesel fuel rebate from miners and transport (while keeping it for agriculture), and removing concessions for accelerated depreciation for investment in oil and gas assets. This would remove about $10.5 billion worth of pro-carbon subsidies across forward estimates, making a significant first step in eliminating the policy tug-of-war between the carbon pricing package and our tax system. It will also start reversing Treasury’s appalling decision to wimp out on the G20 commitment to eliminate inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.

2. Housing supply. We’ve taken three measures aimed at improving housing supply while trying to avoid the distorting, inflationary effects of the first home owner’s grant. One is to increase the government’s “Building Better Cities” scheme. This was announced in the 2010 election campaign as a program to help local councils provide the basic infrastructure needed for residential development — one of the biggest cost issues between developers and governments. The government quietly halved the program from the announced $200 million to $100 million in last year’s budget, but we’ve added $50 million per annum to it, more than doubling the size of the scheme.

We’ve also adopted Joe Hockey’s proposal to better target housing payments to the states to encourage state governments to make land available more quickly and reduce developer levies. This would have no overall cost because it would tie existing special purpose payments to performance benchmarks. But if done properly there would be some funding costs required for a Commonwealth agency such as FaHCSIA to properly monitor state government performance on the issue, so we’ve allocated some departmental funding for that. Thirdly, we’ve established a permanent additional Commonwealth social housing program to provide funding for public housing to the states — conditional on the states maintaining their overall level of existing public housing funding, or in the case of NSW and Victoria, returning funding to levels from before the financial crisis.

3. Infrastructure provision. We’ve adopted the best policy announced during the 2010 election, Andrew Robb’s infrastructure partnership bonds, a scheme designed to leverage private sector funding into infrastructure investment while (unlike the original Keating-era infrastructure bonds) minimising the risk to taxpayers by capping the scheme liability. We’ve set the scheme at $150 million a year, like the Coalition did, with the goal of reviewing it after four years to determine its effectiveness in leveraging infrastructure investment (the original policy is here).

4. Fiscal stability. We’ve also hacked into spending with the goal of reducing Commonwealth outlays, albeit with a phased approach that means we’re not ripping a significant chunk out of the economy while the growth remains a little below trend and the situation in Europe remains unresolved. But we’ve also increased spending or cut revenue in some other areas as well.

We’ve restored the original 2% corporate tax cut associated with the original Resources Super Profits Tax. The logic of the RSPT was strong — in effect use the superprofits being enjoyed by the mining sector because of an historic resources boom to ease the pressure on the non-mining sectors of the economy through a tax cut. The restoration would reverse the errors made by the government (in halving the tax cut when it cut a deal with the big miners) and the Greens and the Coalition (in blocking the cut this year).

But we’ve extended the idea of a super profits tax to the banking sector. The major banks earned around $24 billion in cash profits in 2010-11 and are on course to pass that this year. This is the direct result of an uncompetitive financial sector that is now dominated by the Big Four banks, enabling them to gouge customers and business through interest rates and fees. In the absence of serious efforts by the government to increase competition in banking or even adopt Hockey’s proposal of a financial services inquiry, a banking super profits tax (implemented via a Tobin Tax-style levy on transactions or banking licence fees) would, like the mining tax, remove some of the windfall profits enjoyed by an industry benefiting from unusual circumstances — in this case, government-engineered lack of competition — for the benefit of the rest of the community.

And we’ve hacked into middle-class welfare: the private health insurance rebate will be phased out altogether over three years, removing one of the worst pieces of public policy in the country. To address state concerns about the possible impact on hospital waiting lists, we’ve allocated additional funding for hospitals — $250 million next year, then $500 million per annum thereafter.

We’ve cut back back access to Family Tax Benefit A and B. For Family Tax Benefit A we’ve pulled the second income threshold back from $94,316 to $70,000 and reduced the cut-off point for payments to $120,000 (which is still very generous). We’ve also reduced the Family Tax Benefit B cut-off threshold to $100,000 from $150,000. Costing these changes is difficult for anyone outside government; for our purposes we’ve assumed the Family Tax Benefit A changes would reduce the current $14 billion cost of that handout by $1 billion, and reduce the cost of Family Tax Benefit B by about $200 million. Both estimates, we think, are very conservative.

And we’ve taken the scalpel to the War On Terror, which has cost taxpayers over $16 billion since 9/11. We’ve cut ASIO’s funding from its current levels back to its 2005 levels — leaving in place the massive increase in its funding provided by John Howard, and even leaving its grandiose new headquarters intact, but saving about $130 million a year.

We’ve also recognised the dire revenue situation state and territory governments are finding themselves in due to the collapse in GST revenue growth and sluggish growth in traditional state government revenue sources like property taxes. So we’ve removed the GST exemption for food — a strong growth area in retail spending — which will provide over $6 billion in additional revenue to the states (it will also have the benefit of removing the last stain on public policy left by the wretched Meg Lees).

Finally, we made two additional spending decisions: we restored the foreign-aid cut imposed by the government in the recent budget. Australia is one of the richest nations in the world and has the pretty much the best-performing economy. We can afford to continue to be generous with our foreign aid. And we increased Newstart payments by 10% (we can’t model the exact cost of this, which may be greater than 10% depending on take-up rates, so we’ve used 10%).

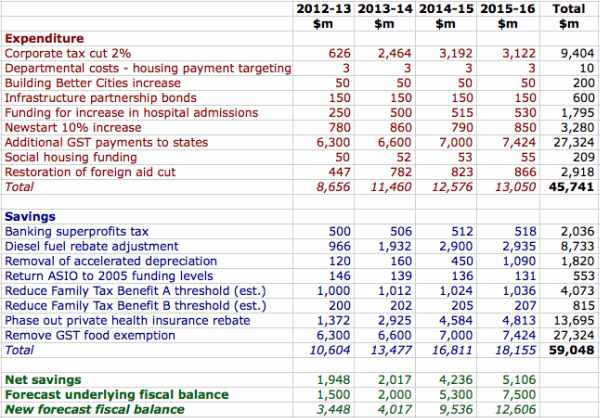

The additional revenue measures will move the budget into substantial surplus more quickly, but in a measured way — a $3.5 billion surplus next year, a $4 billion surplus the following year, then larger surpluses as the cuts to middle-class welfare kick in.

The caveat on all this, of course, is that it’s easy for commentators and economists to spell out what they think should be done, but none of us ever stand for election and face the wrath of voters like politicians have to. Many of these measures would elicit fury from voters obsessed with a sense of entitlement, and from industries benefiting from subsidies like the mining and private health insurance sectors. Some of them would be hated no matter how well they were “sold”.

But we think it’s politically do-able — after all, we haven’t even gone near really serious changes like looking for the tens of billions in tax revenue lost from exempting the family home from capital gains tax, or removing the full $10+ billion in pro-carbon subsidies.

There’s lots of fiscal reform out there to pursue. But it takes more political courage than we’ve seen lately.

*We’re engaging some of the smartest economic brains to design their fantasy budgets for Crikey. But the floor is open to amateur treasurers everywhere — email us your thoughts and we’ll compile the best responses.

Vote #1 Crikey in 2013!

Yep – wouldn’t it be nice – a technocracy run by pundits … make doing the right thing so simple.

Some of these suggestions are both economically and socially sensible – lbut some, ike the GST on food, are politically suicidal.

So one would need to set up some sort of compensation for those on low incomes… so knock a bit off the revenue side there.

But spread the GST to food just to feed the states???? Because they aren’t hauling in as much in stamp duty and other insane taxes they impose on employment and the like? No BK – let the states eat cake I reckon.

But all up 8/10

Generally happy with all the suggestions but I can’t see a banking super profits tax working, not only does it not have the logical nexus of “they are using our mineral and need to pay for it” of the MRRT, but as the banks have already broken the link between RBA rates and what they charge the tax will merely be passed on in the form of higher interest ratres on loans and lower rates on deposits.

As for the courage necessary, well the current govt has brought in a carbon tax and MRRT, means tested private health, restructred FTB and other middle class welfare. initatiated the “builidng better cities” policy and the regional cities program so just because they aren’t doing everything you suggest doesn’t mean they shouldn’t get credit for the courage they have shown, especially when their policies are contrasted with what an Abbott govt is planning to do.

Its just silly populism to claim that the rebate of diesel fuel tax shouldn’t apply to miners. The principle that use of diesel fuel in machinery and in mining equipment shouldn’t be linked to a tax intended to fund public roads is at the heart of this tax.

Like most of the other ideas though.

It’s a great start Bernard.

I wonder whether a phase out (over say 5 or at a stretch 10 years) of negative gearing would be politically achievable in light of the other measures proposed. A primary objective should be to remove the distortions that the tax regime creates.

Peter Ormonde, the states do have a real revenue shortfall problem and a rising expenditure obligation. This has to be addressed if we want to maintain reasonable services. The GST removed a raft of inefficient state taxes and if we don’t fix the state problem we will only encourage their replacement. Someone has to pay for the schools, the hospitals, the police.