I’ve argued before (e.g. here and here) that designing physical environments to encourage or force higher activity levels is neither an effective nor an efficient way to tackle serious health issues like obesity and diabetes.

Here’s a surprising ripple in this debate. The EarlyBirds project in the UK has been monitoring insulin resistance in a randomly selected sample of children for twelve years, from the time they entered school at age five to age sixteen. So far the project has generated more than 60 published papers.

The surprise is the researchers find that children’s level of physical activity doesn’t have a key role in determining if they suffer from obesity or diabetes. That suggests urban design and transport policies aimed at greater physical activity aren’t as important as is commonly assumed.

What matters most they say are genetic factors and food intake. It’s crucially important to understand that “calorie reduction, rather than physical activity, appears to be the key to weight reduction.”

The project effectively involves lining up “300 children at the starting line, firing the gun, and taking snapshots every year as they move down the track to the finishing line at age 16.” Great care has been taken in the design of the study:

The snapshots are sophisticated measures that include BMI, body composition, energy expenditure, physical activity (electronic activity monitors) and metabolic health (blood sugar, cholesterol, insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, arterial stiffness etc). Uniquely, EarlyBird has been taking annual fasting blood samples from these children since they were five years old.

The researchers are forthright about the implications of the project for prevention of diabetes. There are many findings, but I’m primarily concerned with those that relate to physical activity because of the widely assumed connection to potential urban design and transport solutions.

Three findings in particular seem to go against the received wisdom. According to the researchers:

- Inactivity does not lead to obesity – it’s the other way around!

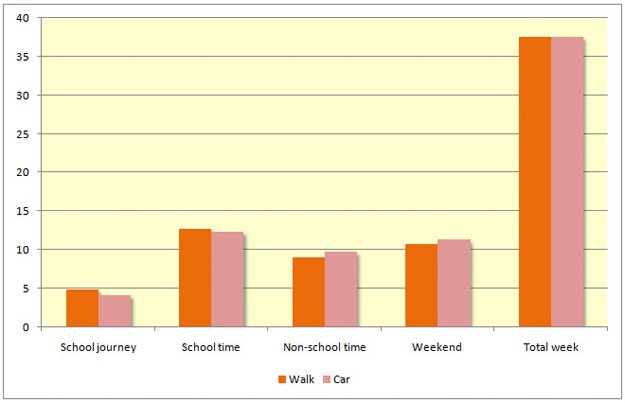

- Children who’re driven to school are just as active over the course of the day as those who aren’t (see exhibit)

- Environmental opportunities, like the provision of open space and sports centres, have no influence on children’s activity levels.

In the researchers own words:

Using time-lagged correlation to imply direction of causality, weight gain appears to lead to (precede) inactivity, rather than inactivity to weight gain. (This is) crucially important because it suggests that calorie reduction, rather than increased physical activity, may be the key to weight reduction …..

The activity cost at the age of 7y of being driven to and from school during the hours 8am-4pm is 16%, but is nil (<0.1%) over an entire 24h. As in the schools study, those who lack the opportunity for physical activity at one period of the day appear to compensate for it at another …..

The evidence we are accumulating suggests the activity of children is “programmed”, either genetically or as a result of very early experience. There is little evidence from EarlyBird studies that the physical activity of free-living children is linked to recreation or environmental opportunity.

The study suggests children’s level of activity is “programmed” prior to them starting school. Most of the excess weight carried by young boys and girls was gained prior to age five.

Rather than being concerned about issues like how much TV school-age children watch, or how much they use open space, the researchers say public health initiatives should be directed to an earlier period of childhood. By the time children get to school it’s probably too late for initiatives to be effective.

Here’s one of the papers written by the researchers and published in the British Medical Journal. It looks at the physical activity cost of driving children to school and contains the data used in the exhibit (including an explanation of the units). It’s the only directly pertinent paper I could find that’s ungated.

The project has some other interesting findings. It indicates social inequality is not associated with physical inactivity and is not a major factor in obesity; the average pre-pubescent child is no heavier than 25 years ago; children who gain excess weight are taller and more insulin resistant than their shorter peers; dietary habits are established early in life and retained throughout childhood; and parents of obese children tend to be unaware and unconcerned about their child’s condition.

The project also indicates the so-called child obesity epidemic is a teenage (i.e. post puberty) problem. The widely-held belief that the entire childhood population is at risk of obesity appears to be wrong:

The trends imply that, before puberty, only a subgroup of the population is at risk. With puberty, the skew in fatness that characterises early childhood gives way to widening of its variance, suggesting a new wave of obesity which this time involves most of the population. The changing pattern suggests that different factors at different ages are responsible for today’s childhood obesity – some operating early in life, and others much later. More than one solution may be needed to prevent obesity in childhood.

Perhaps the level of physical activity has some causal role post-puberty, but at least for younger children, issues like whether they walk to school, use public transport or live at density seem to have little to do with obesity and diabetes.

The only half sensible argument I’ve heard to support conciously designing cities to promote greater physical activity is that measures like higher density are good for other reasons e.g. sustainability. That’s true, but I think claims that aren’t supported, or are contradicted, by evidence should always be avoided on principle. More pragmatically, they can undermine support for the wider objective when they’re eventually debunked.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.