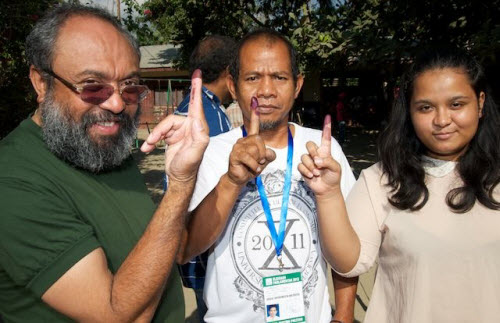

Avelino Coelho da Silva (left) after the vote

Last Saturday evening I was driving around the polling booths to the north of Dili with Avelinho Coelho da Silva, president of the Partido Socialista de Timor (or the PST). Avelino turns to me and says: “Comrade, even if we lose we win”.

We drive on into the falling night to catch the count at the town-based booths at schools in Bidau, Licidere and Bemori then to the “marginal” booths at Tasi Tolu and Tibar at the foot of the mountains east of the city. At the time I thought these were the thought-out-loud musings of a party president staring another failure at the polls in the face. Now, four days, an ocean and country away, I can see the logic in Avelino’s reasoning.

Well after dark we are back in the Dili stronghold of Fretilin at Comoro where we stumble across an unlit rubbled schoolyard to watch the pink-shirted counters hold up each long, brightly coloured vote paper to show the voter’s intention, followed by a loud shout of the number of the party before the vote is laid back on the pile of votes for each party.

At school tables before the election staff sit the party scrutineers. Outside the rooms hundreds crowd around the open louvred windows, keeping tally, drawing early conclusions, exchanging news and gossip from other booths.

Welcome to democracy, Timor-Leste style.

The PST didn’t win any of the 88 seats in the Timor-Leste parliamentary elections this past Saturday but on my reckoning the PST, despite their apparent failures, are one of the biggest winners of this third election in this newest of countries. If the PST can maintain the momentum of the past five years — and there are few reasons to doubt that — it looks set to be a considerable force in Timor-Leste’s future.

For the Australian media the elections barely rated a blip on the radar; not even the discovery of 52 bodies in a mass grave in the grounds of the Palacio Do Governo (not as has been reported in the backyard of Xanana Gusmao’s home) could raise the hacks from their slumber. There were no riots, disturbances or outrages to prompt a last minute rush to gloat. The 2012 campaign was, as Damien Kingsbury noted in Crikey on Monday, wholly uncontroversial.

While many — the World Bank, the IMF and the UN included — see Timor-Leste’s future as a newly-cast neo-liberal state driven by the exploitation of its natural resources others, including Avelino Coelho da Silva, see Timor-Leste’s future cast in a very different mould.

The PST has learnt its lessons from the 2007 elections, where it failed to retain the one seat it won in the 2001 Constitutient Assembly election. The day before this year’s election Avelino told me of the substantial reorganisation and expansion of the PST and that in the lead-up to the 2012 election the Partido Socialista de Timor “only had party structures in five sucos (villages). Now in 2012 the PST has bases in 198 sucos”.

“We have a national congress that meets every four years, we have a Central Committee of the party that meets every six months and the Politburo, the Political Commission — the central committee members who build up the party structure. We have 525 committees based in the sucos — a very big difference between 2007 and 2012. For these elections we have 2000 members of the brigades that distribute material through the sucos,” he said.

“We have introduced a new method. Most of the parties here have no connection with the people that vote for them. Our brigade members go to every household in the sucos to present the PST political platform and we make a political contract with every household that wants to sign up. So [we] had 28,000 families that made the contract with the PST. So if each family votes we will get more than 59,000 votes — if they all vote for us.”

Well, on Saturday not all of those families did vote for the PST.

Crikey encourages robust conversations on our website. However, we’re a small team, so sometimes we have to reluctantly turn comments off due to legal risk. Thanks for your understanding and in the meantime, have a read of our moderation guidelines.