Tony Abbott is a Christian. Did you know that? Perhaps it slipped your notice when he condemned boat people as “un-Christian” for using the back door, or when he told the Australian Christian Lobby that “our civilisation is inconceivable without the influence of Christian faith”, or insisted that Bible classes in schools should be compulsory.

Abbott isn’t shy about his faith. And it’s not just the conservative side of politics playing the game — when Kevin Rudd was prime minister he chased votes at the ACL. Even the self-proclaimed atheist Julia Gillard won’t challenge the controversial School Chaplaincy Program.

But does it work? Do Christians vote for Christians?

Christian voters represent a significant voting bloc. The 2011 Australian Census data indicated that 61.1% of Australians identify as Christian (although this number includes people under the voting age and doesn’t differentiate between those that are regular church-goers and those that are rare attendees — and even those who identify by their religion in the census only).

In 2011, for my honours thesis, I surveyed 1109 Australian Christians to find out how they vote — and, more specifically, how the religiosity of Australia’s political leaders affects Christians’ voting intentions.

The two most important factors influencing voting intentions were not religious — party policies and the political party were key. That is no real surprise — previous research has shown that party policies and the political party are significant factors affecting the voting intentions of the general population.

But the political party leader is the third most important factor, and is considered an important factor that influences Christians’ voting intention. This is consistent with the personalisation of Australian politics and the increasing profile of political party leaders. Think Rudd in the lead-up to the 2007 election. Or nowadays Abbott.

The religion of political party leaders is known by many in the Australian public. Political leaders regularly discuss their own religiosity within public and political discourse; John Howard and Peter Costello highlighted their Christianity to the Hillsong congregation whilst Rudd explained the ins-and-outs of his religion in The Monthly. This would suggest that the religiosity of political party leaders might be an important factor affecting the voting intention of Christians.

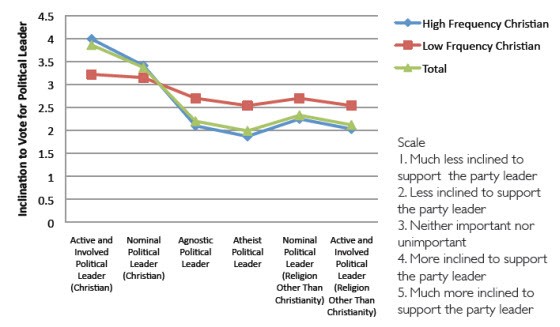

And the survey showed that Christians are indeed religiocentric — they possess in-group favouritism for Christian political leaders as well as a comparative bias against non-religious and non-Christian political party leaders (see graph below). The agnostics and atheists fare worst — Christians would be least inclined to support atheist and agnostic political party leaders.

This causes a problem for confirmed atheist Gillard. Christians are more inclined to vote for Abbott over Gillard. In fact, the research even suggests that Christians would be more inclined to vote for a non-Christian religious political party leader — even a Muslim, for example — than an atheist. Gillard’s religious beliefs, or lack thereof, don’t do her any favours in winning the Christian vote.

And it looks like Abbott has the right idea in spruiking his faith around the country — it turns out that religiously active and involved Christian political party leaders have greater support than nominally religious Christian political party leaders. When considering the Christian vote, maybe Abbott is a better choice than Malcolm Turnbull.

So the order of preferred leader for Christians is: active Christian leader best, nominal Christian OK, active non-Christian tolerable, and atheists at the bottom of the heap. There is clear in-group favouritism towards Christian political party leaders and an out-group bias against non-Christian and (especially) non-religious leaders.

If the polls stay at their current levels, this probably won’t be enough of a factor to make any difference to the outcome of the next election. But if the race tightens up a bit, then the Christian vote could become vitally important in deciding who is the next prime minister of Australia.

There’s another way to look at these findings — as a wake-up call to Australian Christian communities and their leadership. The research shows that Christians are prejudiced against non-Christian and non-religious political party leaders. And, in this, their voting decisions are being influenced by factors that don’t actually have much to do with their leadership ability.

*Grant Power conducted this research for his honours thesis at the University of Queensland, which he completed in 2011

Did you look at any lingering sectarian suspicions influencing voters? There is still some lingering doubt in the US evangelicals will vote for a Mormon presidential candidate.

Grant

Your graph needs to show confidence intervals to have much relevance.

It’d be interesting to see research looking the other way: With atheism increasingly strident these days, are atheists less likely to vote for Christian leaders? I venture to suggest, with no evidence whatsoever, that there would be no major positive bias of atheists towards non-religious leaders, but there might well be a substantial negative bias against religious ones.

As an atheist, I find the final paragraph most interesting in this story.

In terms of voting, unless someone is putting forward an overtly religious set of policies, then their religion is not the primary thing I am concerned about. I am concerned about policies and whether a particular party meets my expectations. Lets face it, political parties in Australia generally have a range of religious beliefs within them – I bet there are a few athiests amongst the Liberal party, for example. If Christians want to be so narrow-minded, then thats their problem.

The results have no meaning beyond comparing two groups of Christians: nothing can be said about how these voter preferences compare to the preferences of the population as a whole, and there is no information about the relative importance of the leaders’ religiosity compared to other factors.

The article also perpetuates the myth that the Australian Christian Lobby is representative of Australian Christians. It most definitely is not.