The whistleblower at the centre of court action against the Australian Taxation Office over allegations she was bullied for lodging a complaint about ATO maladministration is now personally suing the Commissioner of Taxation Michael D’Ascenzo and three other senior ranking officials in the Federal Court that threatens to expose a possible bullying culture within the upper echelons of the organisation.

This action is precedential in Australia as a whistleblower has not previously held individual public officials personally accountable under the Public Service Act 1999.

Serene Teffaha, a senior ATO lawyer engaged as a tax technical specialist, last week lodged a statement of claim in the Federal Court alleging the Commissioner of Taxation, acting on behalf of the ATO, may be vicariously liable for the wilful misconduct and culpable negligence of his public officials that include fellow respondents to the claim, first assistant Commissioner David Diment, assistant Commissioner Margot Rushton and Susanna Lombardi, national director of the small and medium enterprises division.

In 2011, Teffaha and four other senior colleagues lodged the whistleblower complaint with David Diment alleging various maladministration issues associated with the ATO’s high-profile pursuit of high-wealth individual Australians worth between $100 million and $250 million a year. The complainants believed taxpayers were being disadvantaged by not having their objections to assessments dealt with in a fair and professional way.

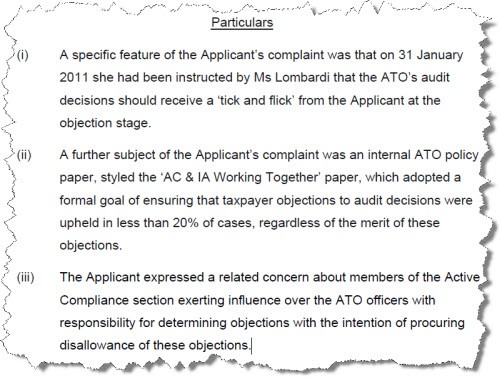

Some of the explosive new allegations raised in the statement of claim include:

- The ATO issued staff a formal target of ensuring taxpayer objections to audit decisions were upheld in less than 20% of cases, irrespective of merit (that is, the target was to disallow 80% of taxpayers’ objections)

- Original decision makers of audits exerted influence over the ATO officers with responsibility for determining objections, with the intention of procuring disallowance of these objections

- Teffaha and others were instructed by Susanna Lombardi that the ATO’s audit decisions should receive a “tick and flick” and affirm those decisions without appropriate consideration of the merits of each individual taxpayer’s objection.

These are serious allegations that strike at the heart of our democratic tax system. Taxpayers have a right under the law to object against their assessment if they believe it is wrong. What Teffaha is alleging is the ATO introduced targets for their staff to disallow objections and to “tick and flick” original decisions made by audit officers.

Crikey has obtained the ATO document confirming the targets. This action would have severely disadvantaged thousands of small business taxpayers; it’s possible some could seek recourse through the ATO, the Inspector-General of Taxation, the Ombudsman and the courts due to this document now coming to light.

Claims David Diment interfered with the whistleblower complaint investigation — coupled with the alleged damage by Susanna Lombardi to Teffaha’s professional reputation and emotional and mental wellbeing, and Margot Rushton’s directions to Teffaha to attend a medical examination with a psychiatrist — will be the focus of the misfeasance in public office, breach of statutory duty and negligence actions outlined in the statement of claim.

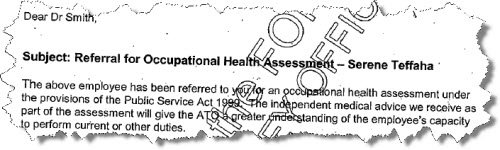

Another area Teffaha’s lawyers will focus on is why ATO officers referred her to a psychiatrist — in documents also obtained by Crikey — within two weeks of lodging her whistleblower complaint, without her knowledge. “Until I received the documents I requested under the Freedom Of Information Act I had absolutely no knowledge that they wanted to send me to a psychiatrist so soon after lodging my complaint,” Teffaha told Crikey.

JA James holds legal qualifications and specialises in public policy, and studied public sector whistleblowing and workplace bullying during her postgraduate studies last year before creating the website APSbullying.com. She told Crikey: “The compulsory medical referral powers under the Public Service Regulations have been abused by senior APS officials in an attempt to discredit whistleblowers’ mental state, undermine their whistleblowing complaint and inflict grave emotional distress. This pernicious practice is masked by the APS as a form of ‘compassion’. Such spin automatically puts whistleblowers on the backfoot.”

Crikey reported in September the ATO had offered Teffaha a $250,000 cash settlement to walk away from the litigation. She was prepared to accept the offer and release the commissioner of taxation from his vicarious liability as long as she was not barred from pursuing the senior public officials personally for their misconduct against her. The ATO refused to settle on that basis.

“My motivation is not money — just accountability,” she said. “It is perplexing the lengths the Commonwealth will go to, to protect the wrongdoers. Unfortunately for the Commonwealth, they are now risking a whole lot more than just money.”

Two recent court cases indicate D’Ascenzo (who will leave the role at the end of this year, to be replaced by Chris Jordon) and the government should be concerned about the latest development in the Teffaha case. The James Ashby and Peter Slipper affair provides a clear example that the courts are no longer willing to allow public officials to hide behind the Commonwealth and its agencies. Last month after Ashby settled with the Commonwealth, Slipper attempted to run the argument he had no case to answer given the release that Ashby was entering into with the Commonwealth. Justice Steven Rares said Slipper was mistaken if he believed the case would just go away as he could not dismiss the case against him:

“I can’t do that Mr Slipper — there’s a complaint against you that you s-xually harassed Mr Ashby and that is at the moment unresolved. I can’t dismiss that case that is unresolved. I can’t get rid of them just because Mr Ashby and the Commonwealth [may] settle. You are locked in this.”

The Commonwealth spent well over $770,000 in fighting Ashby and supporting Slipper. Ultimately they settled Ashby’s claims, but not without great expense to the taxpayer.

And the landmark decision of the New South Wales Supreme Court earlier this month in the Gillian Sneddon case provides another example of how courts may make the tax chief vicariously liable for the actions of his officers. Sneddon was the whistleblower in the former Labor minister Milton Orkopoulos child s-x case. The Court of Appeal ruled the government was liable for Orkopoulos’ conduct as it occurred while he was “in the service of the Crown”.

The ATO can’t comment on a case before court. Crikey put a number of questions to David Bradbury, the Assistant Treasurer with parliamentary responsibility for administrative matters relating to the ATO, on the objection targets that could disadvantage small business taxpayers and the use of public money to fund the legal fees for the alleged wrongdoers. A spokesperson said: “Administrative and operational matters within the ATO are a matter for the Commissioner.”

If you read the memo, it is clearly promoting a model where potential disputes are dealt with through DRP prior to formal complaints being lodged to minimise costly legal proceedings – and that a reasonable way of measuring the success of this model is less than 20% of complaints being “won” by the complainant.

You could perhaps quibble that such a target might not be a true measure of success or might cause dysfunctional behaviour but overall this seems like an eminently sensible approach and similar to what our courts try to do ie solve things early rather than leave it for costly legal procedures.

As to there being a whistleblower case to answer, well that’s a whole other matter.

Thank you Mark from Melbourne for your comment.

I am the whistleblower the article refers to.

If the primary motivating factor driving the ATO is early dispute resolution, the target may appear sensible.

Unfortunately, many taxpayers are stone walled by the ATO at the audit stage as they struggle to resolve their matters. This forces cases into the objections phase rather than early dispute resolution (please refer to the Inspector-General of Taxation’s Review of SME’s to get the exact figures).

The target is set in a vacuum where taxpayers previously expressed concerns may have been disregarded. It is, therefore, inappropriate at all levels to fix a percentage at the objection phase. This is also not in line with the Taxpayers’ Charter.

I colloquially refer to this as the ‘widget culture’. Senior officials in the ATO running business lines and setting standards, without detailed knowledge and understanding of what is actually happening on the ground.

Even in an ideal world where the ATO is effectively applying an early dispute resolution model, fixing target percentages will only focus on quantity outputs rather than quality ones.

[The ATO issued staff a formal target of ensuring taxpayer objections to audit decisions were upheld in less than 20% of cases, irrespective of merit (that is, the target was to disallow 80% of taxpayers’ objections)]

Erm, wut? Surely I’m not the only one to think this is _batshit insane_

The issue of refering Serene Teffaha to attend a medical examination with a psychiatrist is the exact same ploy that airline companies do to pilots when they survive a plane crash.

It’s the first step in self exoneration and the beginning of the blame-game.

@Mark From Melbourne

The tick and flick is not a policy the ATO use to minimise the cost of legal action for SME’s or even to fast track disputes…it serves to minimise legal costs for the ATO and serves their interests above all else.

One question worth asking is – why does the bullying take place on what seems to be a very large scale? In the late 1980s, the then Tax Commissioner, Mr. Trevor Boucher, introduced a system of rewards for ATO officers, apparently based on the money they brought in. We saw the consequences first-hand in the downturn in the early 1990s, when a tax officer tried to brankupt me and my wife, claiming a hugely inflated amount of money. We fought the ATO off, but it cost us our home and just about everything else we had and significantly affected the rest of our lives. The behaviour of the ATO officer conducting the cases was so bizarre, I watched him for several hours afterwards. The entire time, he sat with his arms folded, looking straight ahead, never saying a word, but shaking his head whenever the government solicitor approached him with a proposal. At the time, I considered his behaviour payback for him missing out on his bonuses. However, more recently, I have had an exchange of letters with Ms Teffaha and she advised that these rewards were limited to more senior staff. This prompted me to wonder whether the ATO officer on our case had been directed under threat to take a hard line on the cases I referred to and his odd behaviour, refusing to look anyone in the eye, simply reflected the sense of shame he felt. Perhaps we should look for the money, or other source of power.