Imagine the biggest Ford pick-up truck you have ever seen, and in its tray is a sprawling concoction of tubes and boxes that make up what could be the world’s first mobile carbon capture and storage technology for vehicles.

The prototype, cumbersome and inefficient, apparently reduces emissions from this gas-guzzling monster by just 10%. When refined, a more compact version may achieve a 60% reduction — and the bottled carbon dioxide can be returned to the petrol station to be used as a feedstock for algae. This is either a work of genius in progress, or an act of the greatest futility.

Did anyone think of an electric vehicle? In a country like Qatar, it’s a silly question. The price of petrol is so low it is not even advertised (the cab driver told me it was 75 rial — 20 cents a litre). An EV as a cost hedge on rising fuel costs simply doesn’t make sense when you can refill your SUV for less than $15 a tank.

If you do choose to hold the UN’s annual climate change negotiations in a country that is the biggest exporter of gas in the world, and has as its neighbour the biggest exporter of oil, it shouldn’t be hard to imagine what the dominant theme of many of the discussions would be — the promotion of carbon capture and storage (or CCS) as a fix for global warming. The Doha talks are underway and wrap up on Friday.

One quick glance at the Sustainability Expo that runs with the COP18 climate summit confirms that. This is an exhibition — where the pick-up and the Tesla could be found — that is dominated by the Gulf nations and a single technology, CCS. It’s also overwhelmed by the corporate power of the fossil fuel giants that pervade over this conference and are still desperate to burn as much oil and gas as they can. Renewables hardly get a look in.

It should be recognised that the world’s biggest exporters of fossil fuels are investing heavily in solar technologies. But they do so with one single goal in mind — to free up as much of their oil and gas as they can so they can export it to other countries.

Here, there is no talk of leaving two-thirds of their reserves in the ground, as even the International Energy Agency suggests should be done to meet climate goals. At least, though, the Gulf nations recognise that emissions from fossil fuels need to be reduced. That much is progress. But if you want to produce (fossil fuels) and reduce (emissions), there is only technology that can offer a solution — CCS.

That’s why the CCS industry was looking pretty pleased with itself on Tuesday when 10 of the most influential environmental NGOs — including the Australian-based Climate Institute — announced they were making what is effectively a Hobson’s choice: pledging their collective endorsement for CCS and for it to be bestowed with the kind of subsidies that cause Big Oil, Big Coal and Big Gas to howl to the moon when handed out to renewables such as wind and solar.

There were two principal rationales for their decision. One, the fossil fuel industry simply cannot be moved, and supporting subsidies is the best way to strike a bargain with the Devil. The other is the acceptance of the argument that renewables cannot deliver the target to hold warming to 2 degrees on their own, and that CCS, in some form, will be needed beyond 2050 to deliver what is called “negative emissions” — a combination of biomass, biofuels and CCS.

Clearly, this is putting a fault line down the middle of the environmental movement. The renewables industry has long described CCS as a myth and the image of “clean coal” as a cynical marketing tool designed to protect their industry. They, and most environmental NGOs, suggest if the fossil fuel industry was so convinced of its success then it should invest in it itself. The least it could do was to pay to clean up its own mess.

And it certainly has the resources — the four biggest fossil fuel giants in the western world generate annual profits of around $100 billion, the state-owned firms in the Gulf probably much, much more. And, says the IEA and the UN, the fossil industry already receives more than $500 billion a year in subsidies — more than renewables by a factor of six.

So is this endorsement a tacit recognition that the fossil fuel industry has won the day through its tactics of obfuscation, delay and downright hostility?

The NGOs were simply conceding defeat. David Hawkins, the head of the US-based Natural Resources Defence Fund, possibly the largest and most influential of the NGOs, conceded it was a controversial topic among environmental groups.

“By and large there is still … a disconnect between the analyses of what is required and the position of the fossil fuel industries.”

“Some groups are hostile to the technology, and some are indifferent,” he said. Hawkins agrees many fossil fuel companies are opposing the very policies that are needed to make CCS a reality — specifically a high price on carbon and further subsidies to defray the high upfront cost of the technology. (Like wind and solar, CCS will have a high capital cost; unlike wind and solar, it does not have a low cost of fuel).

“That [the opposition to carbon policies and clean energy policies by the fossil fuel lobby] is still the case in far too many industrial sectors, especially the United States,” he said. “By and large there is still … a disconnect between the analyses of what is required and the position of the fossil fuel industries which are opposing the kind of policies which are necessary.

“That makes it difficult for environmental organisations. Many with good reason in the environmental community, who look at the industry positions, say that you who are supporting for CCS are essentially trying to do something that will prolong life in industry that is opposing the very policies that they now want. They ask, why are you doing that?”

The answer may lie in the report released today by 10 NGOs on CCS. This document accepts that fossil fuel generation is still growing rapidly, and the sheer size of the market makes it impossible to budge and replace with truly sustainable pathways such as energy efficiency and renewable energy. Even if it were technically possible, it accepts that there is significant “economic and political inertia” that would need to be overcome.And, the report suggests, it’s “not prudent” to bet wholly on such a large-scale transformation of the world’s energy system. Instead, it calls for a “balanced and hedged” approach. Some may say they are calling the battle between renewables and fossil fuel interests, and declaring the fossils to be the victors. And then hoping like hell that this technology works.

Certainly, Lord Nicholas Stern says that to meet climate goals, emissions have to be cut by a factor of seven or eight within 40 years. “If you trying to change the world, you’ve got to understand how it works and where it is going. In 25 years, our energy will still be 75% carbon. You might wish it was different,” he said.

And he suggests CCS is cost-competitive, at least with other emerging technologies such as solar thermal. The industry reckons it can deliver the technology at $50/tonne of emissions reduced — about the same as the carbon price in a decade’s time. But don’t count on that coming at zero cost to energy users, because it seems pretty clear the price of fossils fuels is going up, not down.

Brad Page, CEO of the Australian-based CCS Institute, is clearly delighted by the support of these “far-sighted” NGOs, saying it’s not about CCS being against renewables but working with them. As he notes, CCS actually has a smaller role to play in power generation, as well as abatement, by 2050, according to IEA scenarios.

CCS has been deployed in industrial uses, but not yet on a commercial scale for power plants. The first two installations for power plants — one post combustion and one pre-combustion — are only being built now in north America. Page insists that without CCS, deep cuts are not possible, and will be vastly more expensive if CCS is not deployed.

But let’s be clear about exactly what the IEA has actually said — it painted various scenarios of how to reach the 2 degrees target in its Technology Perspectives report released just a few months ago. Yes, it said CCS was critical to reaching the target in the most cost effective manner, but all was not lost if CCS could not come to the party because the gap could be made up by a greater deployment of renewables. And it did note CCS was not progressing as planned.

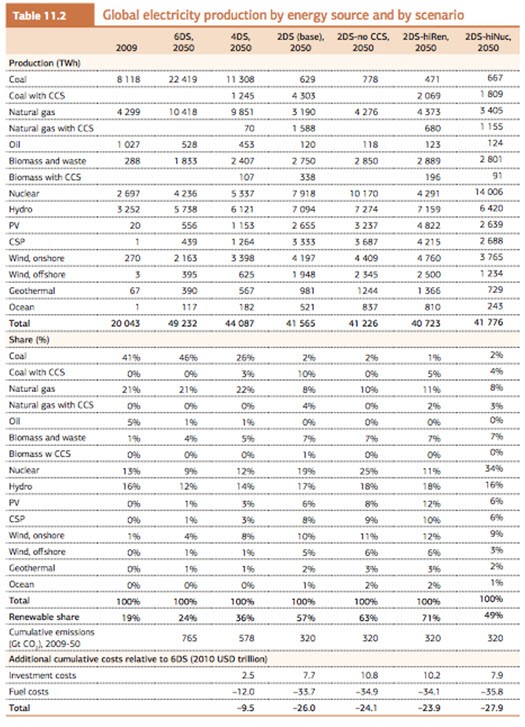

Importantly, the IEA said the cost difference between a 2 degrees scenario with CCS (providing 14% of power plant generation) and a 2 degrees scenario with no CCS was not that great. Bugger all in fact, just 7% once you take into account the cost savings from reduced use of fossil fuels. If you took into account investment costs and fuel savings with CCS deployed, that delivers a total of $26 billion in saved costs. Without it, the savings are still $24.1 billion. So there is no need to panic quite yet — unless, of course, you are a fossil fuel producer.

The graph below from the IEA publication sums it up. It’s a whole lot of numbers, but the key ones are at the bottom, where it outlines the investment required in various scenarios, the fuel cost savings from having a heap more renewables, and the bottom line. (The “6DS”, 4DS and 2DS refer to 6 degree scenarios, 4 degree, etc. )

*This article was originally published at RenewEconomy

*This article was originally published at RenewEconomy

Pie from the sky CCS and deferred disaster Nukes. Oh, dear. Looks like “hope they work out ok” is all we have left if the carbon-cult really can’t be cured. . .

Howard wasted millions, billion ? on carbon capture and nothing of substance has eventuated . After all this time there is still no way to capture/store the carbon without using two thirds of energy or is it one third of the energy ? that a power plant produces . Then there is the question of safety in ensuring the carbon doesn,t erupt out at some stage . CCS is a way to hold back clean technology while using old methods but promising ” new ” methods that are unsustainable to producers and their customer base .

Living in the Latrobe Valley we get promises of exporting brown coal , CCS and various other new developments and they all fall flat because no bank will touch them . Not because the banks are too timid but because there is no sound business base to back them . Pie in the sky ideas that are thought bubbles hoping for Howard like subsidies that keep them in money and deliver zilch . Thats the plan though , make out something is being done while delaying progress of clean renewable energy . Victoria has gone backwards at a rapid rate but is good at spin , well not quite . Two miles distance before you can put up wind turbines but you can have a coal mine 200 yards from private residences . Apparently coal dust etc is ok but wind noise is dangerous even though beneficiaries of turbines don,t get ill but non beneficiaries complain of ill affects . Placebo wind ?

There isn’t a need for carbon capture anyway, the alternatives already exist. There are already companies that recycle green house gas to feed algae for electricity generation and food production. Green house gas also can be re-hydrocarbonise to become fuel again through a process of polarisation for separation of elements and recombining with others.

CCS is political cover.

The energy companies aren’t doing any more than the very mimimum R&D. Australia has one small research plant that vents the CO2 extracted (and doesn’t bury it).

No one is going to let them pump the CO2 into their region anyway – and have you seen the geological maps for suitable regions? None is near the power plants anyway, so you have to truck it anyway!

Regarding using it for geomass, do you realise the difficulty of converting tonnes of CO2 into algae? The size of the ponds? The equipment to harvest it? Its simply impractical.

The real answer is reforming society to consume less energy, and to allow investment of renewable energy start-up companies. Both of these are achieved with my voucher approach to innovation.

http://www.ceisys.com

I really think some environment groups are repeatedly shooting themselves in the foot. If CCS was viable coal companies would be seriously investing in it. Not using it, as they will with this report, as another excuse to block renewables and stave off any real action themselves. Climate Institute would be better off getting NSW and Vic to drop their ridiculous windfarm restrictions and actually trying to get some coal power stations replaced. Without that we can’t get past square one. Coal PR people will be cracking the champers tonight.