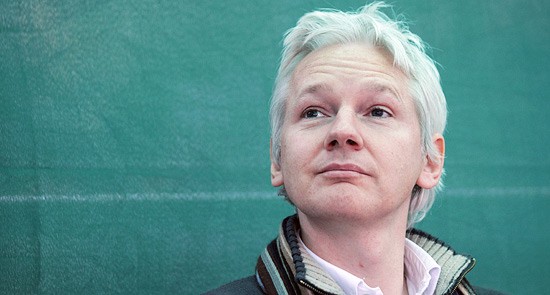

Julian Assange’s intention to establish a political party and run for the Senate could have momentous consequences for the next parliament, regardless of whether he wins or loses.

Assuming he can overcome the procedural and practical difficulties involved in registering a party and nominating as a candidate, Assange proposes to run personally in either New South Wales, where he would face a relatively low hurdle in overcoming the Greens, or Victoria, the state that seems to offer the most promising constituency for a radical candidate.

As with any other candidate in a half-Senate election, the task facing Assange would be to garner 14.3% of the statewide vote, either directly from primary votes or with the aid of preferences.

Victory off the primary vote alone has been achieved three times by Greens candidates (Richard Di Natale and Christine Milne in 2010 and Bob Brown in 2007) and once by Nick Xenophon (in 2007), but it would be an unprecedented feat for a single-issue candidate like Assange.

The Greens achieved the requisite level of support after two decades of coalition-building among varied Left interests, while Xenophon had handled a full gamut of political issues over his 10 years as an independent swing vote in South Australia’s upper house.

Should Assange’s star power not prove a match for that, the question would arise as to whose preferences might boost him to a quota.

An ALP led by Julia Gillard would have a hard time explaining any decision to favour Assange, while a Coalition that seems likely to place the Greens behind Labor in its preference order would have to decide whether he should be extended the same courtesy.

Unless Assange could poach votes directly from the major parties in surprisingly large quantities, his most likely source of preferences in large numbers would be the Greens, whom he would first need to outpoll.

In this he could hope to be boosted by preferences from radical Left parties along with Left-libertarians like the Australian S-x Party and the newly emergent Pirate Party, who can expect to be assiduously courted by both the Greens and Assange. Under the most favourable of circumstances, these sources could perhaps boost Assange in his struggle with the Greens by 2% or more.

The other side of the coin is the destination of WikiLeaks party preferences should Assange, or indeed any of his colleagues in other states, fall short.

Of great significance here is the rule which allows parties to lodge up to three preference tickets and have their votes divide equally between them, which is often used by minor parties to avoid favouring one major party over the other. This would presumably sound inviting to Assange, given the state of his relations with the present government.

Under this scenario, a substantial chunk of left-of-centre Senate votes that would normally go to Labor ahead of the Coalition would instead divide evenly between the two (remembering always that this only applies to those who vote above-the-line).

Where the Coalition does especially strongly, that would lower the hurdle for them in achieving a result of four Coalition to two Labor, as opposed to the more common outcome of three-all. It could equally prove decisive in a more complicated scenario such as SA’s, where the likelihood of Xenophon’s re-election could leave Labor and the Coalition grappling over the sixth and final seat.

To take the speculation a stage further, Assange’s entry into the electoral fray has the potential to allow an incoming Coalition government to secure legislative aims that would otherwise be beyond it, up to and including the repeal of the carbon tax.

As a Victorian, I’d vote for him. He’d probably be a really crap politician, not willing to do the boring mundane stuff, but he’s a shit-stirrer, and he has beliefs that I understand better than I understand most on the Senate ticket, and frankly I don’t think we’d do worse than we currently do.

Kim Carr and Stephen Conroy we all know, but who knows anything at all about Bridget McKenzie or Gavin Marshall?

Sounds like one of the most likely results is he could split part of the soft left/progressive vote and risk making the senate more conservative? Possibly also doom any chance the Greens have of taking a senate seat off the Libs in the ACT if he runs a broad wikileaks ticket.

Interesting idea …. though at present he can’t leave London so couldn’t physically assume his Senate seat during votes. How would the coalition benefit if his vote cannot be counted?

In other words, Australians have the option of taking a hatchet to the cannon’s securing ropes.

Assange should run as a Pirate Party senate candidate. They already have the policies which are aligned to Wikileaks. Assange would lift the party’s profile (and vote) nationwide.