Danger of being anti-Catholic. In the Liberal Party’s campaign planning room they are obviously worried about the electoral impact of Tony Abbott being seen as somehow “anti-women” because of the views he has expressed over the years on subjects like abortion and in-vitro fertilisation. How else to explain the daring decision by Peta Credlin, his chief of staff and wife of Liberal Party federal secretary Brian Loughnane, to go public with her own experience of her boss’s views on such subjects?

On my reading of her interview published in the News Limited Sundays, Credlin at least made a case that Tony Abbott’s views on such vexing social questions are not nearly as black as his critics are wont to describe them. The major reservation I have about the Abbott views is not that he has personally supported the teachings of his Catholic faith but that the political spinners are trying to hide his views.

Far better, methinks, to adopt a position of being true to his Church’s teachings while declaring that on such questions of ethics and morality he would not try and impose those teachings on a government he led. Rather, in a parliament with an Abbott supporting majority, while strongly arguing his case, he would not hinder the right of all members to do the same thing and vote according to their own consciences.

In the face of an approach like that, a continual harping on the Opposition Leader’s personal views would open Labor to the danger of being seen as not so much pro-women as anti-Catholic. And that’s a situation where vote losing might be greater than vote winning.

Shortening the “milling” time. Too late to be of use to those charged with dealing with today’s catastrophic fire risk in New South Wales, but a report published overnight in the the United States might be of help next time.

It’s a comprehensive study, impossible to summarise in a short snippet, with one aspect I found particularly intriguing being the way researchers have found that people seek social confirmation of warnings before taking protective action.

Before acting in response to a warning, people generally seek confirmation from others. The resulting process is known as milling, in which individuals interact with others to confirm information and develop a view about the risks they face at that moment and their possible responses.

Milling creates a lag between the time a warning is received and the time protective action is taken. Yet few approaches to formulating and delivering warnings focus on shortening this milling time. Indeed, one important lesson from past research is that without careful attention to the process of milling, the introduction of new warning systems may increase rather than decrease individuals’ delay in response. Social media provide a new way for these interactions among individuals to occur. Although many first responders believe that social media have given them less control over the warning process, informal dissemination of messages has always played an important role in the warning process.

Indeed, one might conjecture that the inherently social nature of social media might help reduce milling time, but whether this is true and under what conditions is an open research question.

The report points to some of the difficulties standing in the way of more widespread use of social media by emergency management organizations. Drawing on lessons he learned from discussions with fellow local emergency managers, Edward Hopkins, Maryland State Emergency Management Agency, noted the follow challenges:

- Limited understanding. Despite growing appreciation of the role that social media can play in disasters, many emergency managers remain more comfortable with traditional media, and not all are aware of the potential advantages of social media as a tool for alerts and warnings. Some of this is surely a result of generational or cultural differences.

- Loss of control. When they use social media, emergency officials cannot control which information social media users share, which raises concerns that they might lose control of messaging or face civil liabilities if misinformation is shared. By contrast, in the traditional command-post style of information dissemination, long-standing relationships between the press and emergency managers provide some sense of control over what information is disseminated as well as well-understood opportunities to disseminate corrections as needed. It is the belief of some officials that with social media, misinformation may spread more rapidly and continue to spread even after a correction is issued.

- Institutional limitations. Especially in an era of shrinking budgets, it is hard to find the resources to evaluate and adopt new tools and technologies, or to invest in the training necessary for their use. Also difficult is securing new resources to cover the additional staff time necessary to monitor social media activity. As a result, although emergency management personnel may try to experiment with social media use, they may find that their other (day-to-day and emergency) responsibilities crowd out the possibility for this work.

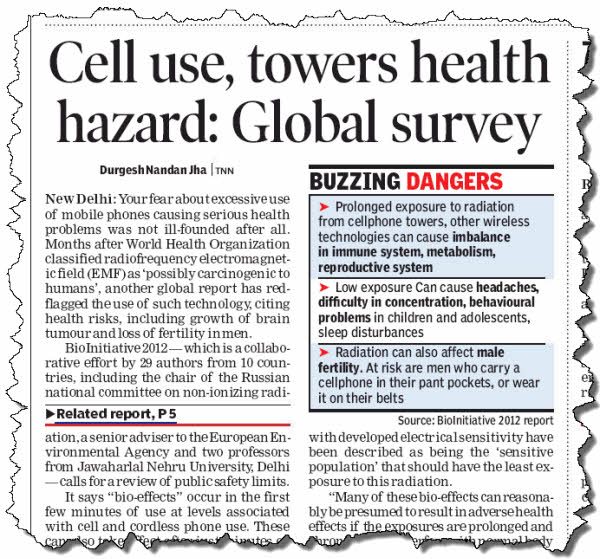

Don’t put it in your pants. A warning via the front page of this morning’s Times of India:

News and views noted along the way.

- Why schools rate girls better than boys. It’s biased teachers that cause it.

- The state of macroeconomics: John Quiggin on how it all went wrong in 1958

- In Asia, Ill Will Runs Deep — Japan is afraid of China’s rise, because the Chinese economy is so much more dynamic than Japan’s. And China is troubled by Japan, because the island nation seems to act as an unsinkable American aircraft carrier just off its coast.

- The Beatles of Comedy: Monty Python’s genius was to respect nothing — these days even an annotator of Monty Python would sooner seem humorless than culturally insensitive. But how far have we come, really, if we now require footnotes to assure each other that we don’t approve of husbands strangling wives?

- Irish newspapers and the battle to control online content Attempts by Irish newspapers to charge sites just for using links to their content are a harbinger for a huge battle to come.

- The Reason We Lose at Games: Implications for Financial Markets

After-all almost the entire make-up of the coalition front bench members are of the RC persuasion. The public should be aware when going to the polls this year that a vote for the coalition could result with an impending swing to RC church conservatism once the coalition is in power.

The Kenny article ( OZ today)is a real issue but it also clouding other gender issues where Abbott needs to be more forthcoming.

It would be sad if Bill Hillfinger is right about the Liberals.

It is already of concern amongst moderate secular Liberals that the party is beginning to look and sounds like the DLP of old.

Abbott in today’s interview is far from being forthcoming(ABC)but the statement of governing for all Australians is going to come increasingly under the microscope as his track record suggests otherwise on all kinds of gender issues not just IVF and Abortion.

In Queensland the issue of birth control being taught in schools is looming its ugly head as well.

Howard tinkered with the History curriculum so the use of ideological bias in not new to conservative governments.