A conservationist sends out a fake press release about a highly polluting coal development; national opprobrium follows. But where’s the outcry when a conservation group cosies up to business, allowing the use of its logo on a product some experts say is environmentally harmful in return for an undisclosed sum?

There have long been rumblings within the green movement about the fundraising practices of WWF, a big international player which bills itself as “the largest conservation organisation in Australia” (it turned over $24 million domestically last year). The latest case involves a microscopic Antarctic beast, a vitamin giant and a mystery sack of cash.

WWF-Australia signed a three-year deal with health product purveyors Blackmores in late 2012 to promote its Eco Krill Oil, which is made from krill taken from Antarctic waters. The oil is said to provide “omega-3s for brain, heart and eye health”. Blackmores gets to use the WWF logo on its krill oil, in exchange for Blackmores paying WWF an amount of money which neither party will reveal publicly.

The trade is substantial; WWF says more then 20 million capsules of krill oil are chugged down in Australia each year, worth more than $15 million.

There are other brands of krill oil around, but only Blackmores can use the WWF logo. The reason? Blackmores’ krill oil secured Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certification, which is supposed to indicate that seafood is sustainable. Such certification is controversial.

Krill is not a threatened species. But it is at the bottom of the food chain — seals, penguins, whales and plenty of other species depend on it — and it is taken from the pristine Southern Ocean. Blackmores argues the krill is found in “great abundance”, and says the company uses a “gentle harvesting” trawling technique which reduces bycatch of fish, seabirds and seals.

MSC agreed to certify Blackmores on the grounds that krill stock (and the wider ecosystem) could sustain the harvesting, and the management of the harvesting was acceptable. Environmental groups like Pew, Greenpeace and the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition (ASOC) lodged objections during the assessment. WWF raised some concerns about krill harvesting, but was more muted than the other conservation groups — and did not join them in lodging an official objection to the certification.

Dr Cat Dorey, co-ordinator of Greenpeace’s Sustainable Seafood Programme, says fisherman shouldn’t be going to one of the earth’s last wild places to “hoover up a species that is a key part of the whole food chain”. Little was known of the impact of climate change on krill. “We should just leave krill alone,” Dorey told Crikey.

“It’s is an extreme example of fishing down the food chain — we’ve fished everything else so now we have to travel to the far ends of the earth to one of the most sensitive unspoilt ecosystems to fish something we can’t even eat ourselves.”

Dr Michael Harte, national manager of WWF Australia’s marine section, defends the Blackmores deal, telling Crikey that MSC certification represents “the highest standard of sustainability in seafood, fish and krill oil products”. Krill is highly important to the Antarctic marine ecosystem, and the growing demand for krill products could risk that ecosystem; best-practice management is required.

“We believe that krill, like any other fishery, can be managed sustainably,” Harte said. “Blackmores should be congratulated for seeking out MSC certified krill for their krill oil product. It is a fantastic example of best practice in action.”

The Blackmores/WWF deal is rumoured to be worth more than $100,000, but it’s a closely guarded secret. “WWF does not disclose the specific income from each of our corporate partners,” Harte said.

The vitamin giant wouldn’t say either. “The licence fee is commercial in confidence, which is standard policy for WWF-Australia’s partnerships and Blackmores are respectful of this,” the company said in a statement.

This is standard practice for WWF, which has had business at its heart since its Australian arm was established with the help of $20,500 in corporate donations back in 1978. According to the 2012 annual report, 10% of its income came from corporates, or $2.42 million. It’s not disclosed which corporates donate or how much, but the annual report talks glowingly of Blackmores, Coles, John West, Tassal, the Coca-Cola Foundation, palm oil companies, Bunnings, Kimberly-Clark Australia, McDonald’s and beef companies JBS, Teys, and Merck.

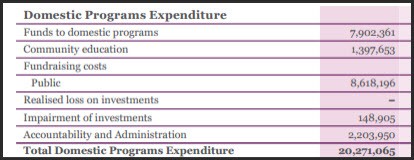

And that income didn’t all go to saving tigers. Last year, WWF spent more on fundraising than it did on domestic conservation programs. The NGO spent $7.9 million on domestic programs, $1.4 million on “community education” and $8.6 million on “fundraising costs”. A spokesman says fundraising costs include direct mail, TV ads, telemarketing, face-to-face activities and online engagement. (WWF says it usually aims for a 65:35 split on conservation to fundraising spend, but has ramped up the fundraising temporarily.)

Excerpt from 2012 WWF Australia annual report

Asked if WWF is compromising its environmental integrity in order to secure donations from corporates, Harte says working with business and industry is key to a sustainable future. Partnerships with the most influential buyers of key commodities drive real change and could transform the whole supply chain, he says.

But conservationists working for other NGOs expressed disquiet to Crikey. WWF is seen within the sector as being the NGO that works most closely with business, and critics accuse it of excusing or masking some corporates’ unimpressive environmental practices.

One insider says when environmental groups accept funding from business, it could compromise the group’s capacity for clear-eyed critique. Another says while WWF in Australia is fairly good at remaining uncompromised, doing cash deals with corporates is a problem; the staffer claims some companies sign deals with WWF and then used them to hide behind, declining to work with other NGOs which have tougher conservation demands.

What a beat up…

I’ve long wondered (or since they’ve been able to encapsulate them at least), “With their ability to “harvest” such large amounts, where would that “excess” they’re taking now, to supplement our “needs”, have gone if not to these harvesters/nets? Would they have gone to waste and just died, or to other parts of the natural food-chain, to feed other marine life in a healthy marine environment?”

[Same way as the sardine is headed, after the more commercial wild tuna and other species being overfished, beyond sustainable levels?]

klewso

I think they would have been eaten by all the whales that aren’t there anymore, so they are probably “spare” krill and we would be up to belly-buttons in the stuff (or fast breeding smaller whales) if it weren’t for the harvest.

That “gentle harvesting” trawling technique (in the link) sounds a lot like the “supertrawler” proposal we were supposed to be so upset about a few months ago. Gosh this stuff is confusing.

Not happy WWF Really NOT HAPPY… you now lose my $20 per month donation.

Blackmore’s you have lost your credibility, and my business. Money before Morals…is the depressing bottom line for this lot.

Is there a resource left on the planet humans won’t exploit to the detriment of other species?