Media coverage of the Grattan Institute’s Mapping Australian higher education report released this week has focused on the public policy implications of doubtful university-related debt through the HELP scheme. One missing link in the media coverage is the link between discipline studied and chances of getting a professional job.

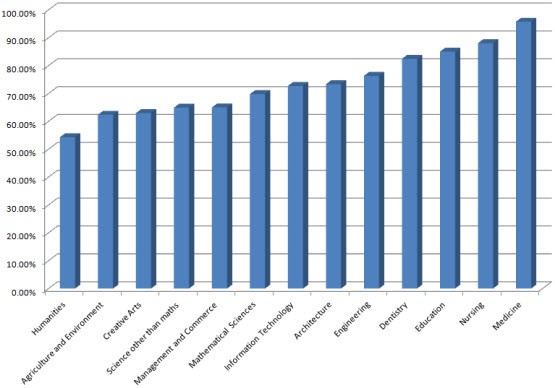

The report uses 2011 census data to explore job prospects of bachelor-degree graduates by the main discipline studied. As we would expect, there are big differences between degrees. People with degrees in health-related disciplines generally have a very good chance of getting professional or managerial jobs — about 90% of those in work and not currently studying for many sub-disciplines. People with degrees in the humanities and social sciences find it much more difficult to find work matching their qualifications. Between half and two-thirds, depending on discipline, are in professional and managerial jobs.

Bachelor-degree graduates in work and not currently studying who have a job as “managerial” or “professional”

The federal government has strongly promoted university science education, though for 2013 it quietly increased the price of science subjects up after three years of heavy discounting. From a marketing perspective, the government’s selling of science was very successful. The number of people applying for and enrolling in science degrees soared.

But there never was any strong evidence that more science graduates were needed, and the 2011 census confirmed the labour market is over-supplied. Except in earth sciences, bachelor-degree science graduates have below-average employment outcomes.

Turning to the issue of the likelihood of HELP debt not being repaid, taxpayers stand to lose as much as $6.2 billion of the $26.3 billion in student debt — former students are predicted to earn less than $49,000 a year in Australia through most or all their lives.

Some of these HELP debtors are working overseas. The non-repayment of their student debt is a policy issue, but unlikely to be a personal problem for those involved. The people in Australia but not earning more than the income threshold are a more interesting, and perhaps more concerning group. Was their higher education an unsuccessful investment? Does their experience provide a warning to others seeking higher education?

We know too little about the people not paying back their HELP debt. The HELP doubtful debt figures are based on advice from the Australian Government Actuary. There is little public domain information on how they calculate doubtful debt, other than that it is based on Australian Taxation Office data. The ATO possesses the most accurate records of income within Australia, but collects limited information on other potentially important characteristics. It has no data on which disciplines HELP debtors studied.

Another missing characteristic in ATO data is whether the HELP debtor finished a degree or not. About 20% of people who start university do not complete a qualification. They are likely to earn less than graduates, and so are perhaps less likely to repay their HELP debt. We know that completions decline with ATAR, and so this aspect of the doubtful debt problem may increase as more low-ATAR students are enrolled.

The ATO does collect information on gender. We know from the census that full-time labour force participation for women with bachelor degrees declines in their 30s, usually due to raising children. Part-time work or leaving the labour force are obvious reasons why someone might earn less than $49,000 a year.

But ATO data shows that women owe 57% of all HELP debt, which is what we would expect. Women have had been around this share of total enrolments in recent years. With HELP debt taking on average about eight years to pay off, perhaps most female HELP debtors repay before leaving full-time work.

We need a better understanding of the causes and correlates of HELP doubtful debt. It could help prospective students make better decisions, and reduce how much the HELP scheme is costing other taxpayers.

*Andrew Norton is the higher education program director at the Grattan Institute and authored the Mapping Australian higher education report

A humanities degree is wasted because you do not end up in a “professional” or “managerial” position? I’m sorry but this totally fails as an assessment of whether a degree course was worth doing. Many humanities students end up as authors, film makers, painters, and tonnes of other jobs that wouldn’t be in either of those categories and yet I would still see them as being successful.

This article seems to equate success purely with what you’re pay ends up being. Few humanities students would give pay rates as a motivation for doing a degree.

As someone who did a science degree, I’m really glad there are so many humanities students who make our world a much more interesting place.

I’m with Saugoof. The answer to the question “Was their higher education an unsuccessful investment?” should not be measured only in financial terms.

I have a Science and IT degree, and now that I can afford it I’m going back to study humanities and get a more rounded education. It’s a shame it has to be this way.

Saugoof – I think Andrew’s point is that humanities graduates are, on average, less likely to earn above the $49 000 p.a threshold at which HECS repayment becomes compulsory. Of course the “success” of education can’t simply be measured by the monetary returns it provides through later employment. The issue here is that a substantial portion of students never pay off their loans – or even worse, are never able to.

While I trust that my sons, both in their early 20s with Hons degrees from ANU, are ‘making the world a much more interesting place’, I would also prefer that they be able to support themselves. Older son, with a 1st in History, is currently pursuing a PhD because there were no suitable jobs on offer. Younger son, with a degree in Sociology, couldn’t even get a call-back for entry-level public service positions and is now doing essentially manual labour in big-box retail. Both are of the (sadly mistaken?) view that their entry into the workforce should give some recognition to their academic achievements.

HELP debt is not a problem.

The Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education portfolio budget statement for the 2012-13 budget reported that 16% of new HELP debt was not repaid in 2010-11. From the average change in new debt not repaid over the previous 3 years the Department estimates that the proportion of new debt that will be unpaid will be 17% in 2011-12 and 18% in 2012-13.

While this is increasing, perhaps as HELP is being expanded for vocational students who earn lower incomes than higher education students and thus are less able to repay their loans, the Department projects HELP repayment levels to remain high.

Commonwealth of Australia (2012) Budget – portfolio budget statements 2012-13 Budget relates paper no. 1.13 – Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education Portfolio, page 101.