Ted Baillieu’s big idea for the future planning of Melbourne is one he’s apparently borrowed without acknowledgement from his predecessor, former premier John Brumby. Brumby was enthusiastic about the idea of Melbourne as a city of villages where people could “work closer to where they live”. Baillieu’s version is essentially the same — he says Melbourne should be a “20-minute city”.

Speaking at a public forum on the development of the new metropolitan planning strategy for Melbourne on Saturday, he said:

“In many parts of the world, cities operate on a 20-minute basis — there’s no reason why we can’t grow that in this city. If you can get a job within 20 minutes, or if you can get to a shopping centre within 20 minutes, then you’ve got a great starting point for a great city.”

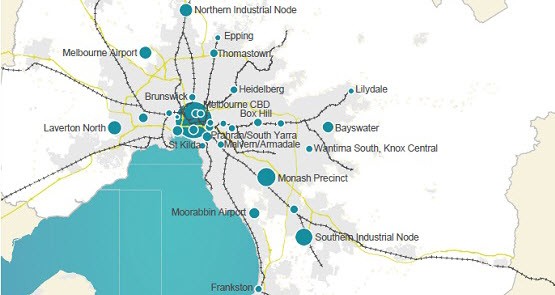

The notion of the “20-minute city” is set out in more detail in the discussion paper released late last year (including the map above) by the Ministerial Advisory Committee, which was set up by Planning Minister Matthew Guy to advise him on the metropolitan strategy. The paper indicates the idea includes all transport modes (page 64):

“Whether the 20-minute travel distance is by walking, cycling, bus or car will depend on the area and the habits of its residents. Better services and cheaper travel alternatives will provide choice for residents.”

At first glance it sounds like mother’s milk: everybody would want to live in a city where everything is really close by. But nothing comes at nil cost, so to appreciate if this is a worthwhile objective we need to understand what we would have to forego in order to have it.

There are serious problems with this idea. For a start, Melbourne already is a 20-minute city, at least in relation to local services. I doubt there’s anywhere in Melbourne, including the outer suburbs, where residents can’t get to a shopping centre within 20 minutes by car.

Most suburban trips are already local. For example, 70% of trips by residents of the City of Casey in the outer suburbs are to destinations located in either Casey itself or the adjacent City of Cardinia (the corresponding figure for Cardinia is 83%). Given around 90% of households in Melbourne have at least one car (and most have two or more, especially in the suburbs), Baillieu’s grand vision doesn’t sound like much of an advance.

But there are some trips that take far longer than 20 minutes. While a lot of jobs are already local, the average one-way journey to work in Melbourne, for example, takes 36 minutes (it’s 30 minutes by car and 55 minutes by public transport). Journey to work travel times flow from a central fact about cities — they are big places that thrive on diversity and foster specialisation.

Some activities aren’t spread evenly across the metropolitan area but cluster in a limited number of locations. High-paying jobs that benefit from agglomeration economies concentrate in a few dense locations like the CBD and some larger suburban centres.

There’s also ample evidence that workers have a consistent average travel time “budget”. They will willingly travel farther and longer to get to a better job — perhaps it pays more or offers superior conditions. For example, workers who live in Melbourne’s middle-ring suburbs commute one-way on average for 36 minutes and travel on average 12.5 kilometres. Those who live in the outer suburbs commute for much the same time (38 minutes) but travel 19 kilometres.

The few who work in the CBD and can afford a downtown apartment might well get to their high-pay jobs within 20 minutes’ travelling time door-to-door, but that’s simply not an option for the vast majority of residents in any of Australia’s big cities.

And it’s not only jobs. Many activities benefit from economies of scale and so tend to be centralised at locations of high accessibility. Trips to destinations like the footy, concerts, universities and nightclub strips certainly take a lot longer than 20 minutes for the greater than 90% of the population who don’t live in the inner city.

People who live in big cities also don’t confine their friends, lovers and family to those who’re within 20 minutes of home. Regard must be given to the differences within households. Even if one member can find a local job he’s happy with, it’s more than likely his partner — and perhaps children too — can’t.

Crikey encourages robust conversations on our website. However, we’re a small team, so sometimes we have to reluctantly turn comments off due to legal risk. Thanks for your understanding and in the meantime, have a read of our moderation guidelines.