A lot of the discussion on autonomous (or driverless) cars focuses on the considerable problems of implementation, particularly the transition period during which human-controlled vehicles are likely to share road space with machine-controlled vehicles.

This could take decades so there’re bound to be serious problems. Some of them will be technical but most will be political. What would the reaction be, for example, the first time an autonomous vehicle runs into a pedestrian?

I think there’s a parallel here with the introduction of cars at the end of the nineteenth century. Back then it wasn’t obvious cars would succeed on the scale they ultimately did.

They were expensive to buy and operate for all other than the extremely rich. There was limited supporting infrastructure such as fuel stations and all-weather roads.

The vehicles themselves were mechanically unreliable, difficult to control and operate, and unsafe for occupants. They were seen as a serious threat to pedestrians and horses as they were capable of what must’ve seemed incomprehensible speeds.

Moreover, there was active opposition to cars. As Aaron Wiener notes in the Washington City Paper:

….in the early days of the automobile, when the technology itself was being questioned and few rules existed to govern traffic and parking, there really was a war on cars. Driving could get you arrested in some places, whacked with stones in others, and actually shot by gun-wielding police in at least one. This wasn’t a philosophical debate over parking or bike lanes. It was a real, knock-down, drag-out battle.

I don’t think autonomous cars will provide the same quantum leap in mobility and productivity today that cars and trucks offered back in the early twentieth century, but they nevertheless offer a compelling, even irresistable, proposition.

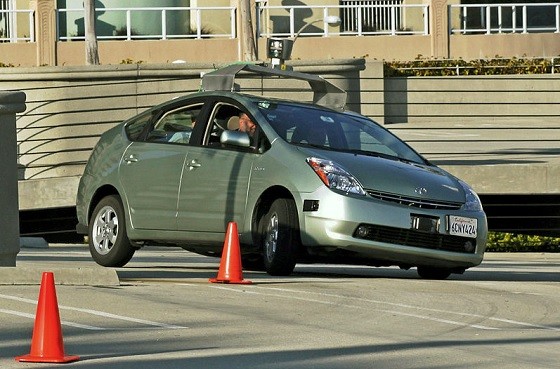

Google expects to release its autonomous vehicle technology in five years and GM, Audi, Nissan and BMW all expect to have driverless cars on the road by 2020. Even if we add on an extra 20 years for hyperbole, it’s an idea whose time seems close – certainly within standard planning time frames.

Subject to the technical problems being overcome, fully autonomous cars have the potential to lower the capital and operating costs of travel, increase speeds, and make time spent in-vehicle more productive and more comfortable.

Since intelligent vehicles are much less likely to have accidents, they can be considerably lighter. They’ll consequently be cheaper to make, use less fuel and be more amenable to alternative power systems.

They’ll be faster too because inter-connected computers can manage higher speeds better than humans as well as intelligently manage congested traffic conditions.

Since they won’t require a driver, passengers can spend time working, reading, getting drunk or sleeping.

People who currently can’t drive – like the young, the elderly, the infirm and the drunk – will enjoy greatly enhanced mobility.

There’ll be many fewer accidents and lower insurance costs. Households will only require one car, since an autonomous vehicle can drop off one member and return by itself to pick up and transport other members.

Autonomous cars will spend less time searching for parking spaces. They can drop passengers at their destination and then take themselves to the nearest car park.

Probably the most cited potential benefit is greater road capacity. Because autonomous cars can travel faster and closer together, roads could take more vehicles, delaying the need for additional infrastructure.

Some of the biggest benefits though would come from car-sharing. Rather than own one or more vehicles that sit parked most of the time, households could summon a rented vehicle as and when needed, much as they currently use a taxi.

Car-sharing isn’t an inevitable way autonomous cars would be deployed but they make the possibility plausible. Sharing would save households money and lower income travellers could avoid the capital cost hurdle of car ownership.

For the society as a whole, sharing would reduce the number of vehicles that have to be manufactured and the number of parking spaces required in sought-after locations.

The average size of the vehicle fleet could also be smaller. Since the majority of trips involve only one or two persons, most vehicles could be smaller and lighter.

Autonomous cars won’t eliminate traffic congestion. Nor will they obviate the need for public transport in dense locations, but they could make it cheaper by eliminating the expense of drivers. That would also be true for trucks and delivery vans.

But there would also be downsides. If travel is cheaper, faster, and more comfortable, it lowers the cost of ‘driving’ ever further.

People can consequently live further from work and other key destinations. That’s how trains and trams, and subsequently cars, facilitated suburban sprawl.

Easier travel provides a private benefit – it increases the range of housing/locational choices available in terms of space, amenity and affordability, as well as easing pressure for redevelopment within established areas.

But as we know from the history of urban sprawl over a century and a half, it can also impose social costs.

Autonomous cars could increase travel in other ways too. Even trivial decisions could lead to more travel – for example, some households might order the car to do multiple automated shopping trips on a just-in-time basis rather than do all shopping in one trip.

Those whose travel options are currently restricted because they can’t drive would likely travel more if autonomous cars were available. That’s a private benefit, but could have a social cost.

Another issue is the potential for sharing autonomous cars might be more limited than much of the discussion assumes. Many travellers might prefer to have their own driverless car. They might not be prepared to wait for a shared vehicle to be dispatched or they might like the customisation potential a dedicated vehicle offers.

If car companies and developers are right that the technical and political problems associated with driverless cars will be overcome sooner rather than later, then policy-makers should be thinking now about what implications they might have for the functioning of cities.

Although they look 20-40 years ahead, neither the recently released draft metropolitan strategy for Sydney, nor the discussion paper for Melbourne’s strategic plan, seriously examine how autonomous cars might affect the long-term future of these cities.

From today’s perspective there are still big questions about the technology, but it’s a very big call to effectively assume autonomous vehicles will have no impact over a time frame of 20-40 years.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.