In January, Prime Minister Julia Gillard outlined her economic and political strategy for the year, in a speech that became more famous for naming the election date than for the strong strategy that lay behind it.

That strategy, structured around the NDIS, Gonski and managing the economy for working Australians across a whole range of issues during the time of an overvalued dollar, was clear, consistent and coherent, both politically and economically.

But since then, the government’s political and economic strategy has fallen apart in the face of faltering revenues. By the time the Prime Minister rose two weeks ago to reveal that revenue for the current financial year had been written down by a further $7 billion and that “grave and urgent decisions” were required, the strategy had been reduced to incoherence.

The settled line from both the Prime Minister and the Treasurer was that the government was going to be fiscally disciplined, but not “cut to the bone” like Opposition Leader Tony Abbott would. Moreover, the government was still committed to its big-ticket policies; Gonski and the NDIS.

As if explaining why revenue had been written down because of low nominal GDP growth wasn’t nuanced enough already, explaining that you were going to cut, but not as much as the other guy, while still spending up big, was nuance on nuance.

This 2013-14 budget fails to resolve this dilemma. It doesn’t deliver a convincing and coherent story about where the government is going, unless you try hard to resolve a series of contradictions.

So, the government will make a virtue of its tough decisions. And yes, there are some tough decisions: dumping the baby bonus (it should have been dumped entirely, not replaced with a FTB-A payout, but anyway) does take guts. So too, dumping the net medical expenses tax offset. Labor will cop it from all directions on these decisions and a myriad of smaller decisions throughout the budget papers, but they’re excellent decisions to curb the growth in spending not merely over the forward estimates but in decades to come.

But Labor has also chosen, once again, to make less developed countries pay the price for its budget stringency, with a big cut to projected foreign aid increases. And much of its “savings” measures are, as in previous years, actually tax rises, in particular from the painless source of cracking down on corporate tax avoidance, something voters are sure not to mind. The government will now spend more in coming years than it had previously anticipated.

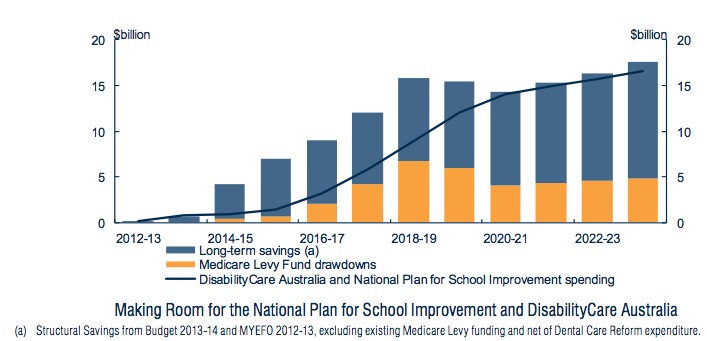

Nonetheless, the government has provided a map of its long-term savings, out to 2024. The nature of the savings build-up is appropriate, even if its speed is not — virtually nothing next year, but mounting over the forward estimates over the final years of the decade when NDIS spending kicks in.

That’s why, despite what he’ll say, opposition treasury spokesman Joe Hockey will be delighted with the budget. It does improve the long-term sustainability of fiscal policy, if not necessarily with the swingeing cuts he keeps suggesting he wants, and makes his job as Treasurer easier, especially in 2016 when he’ll probably be producing his first pre-election budget.

The $16 billion-odd improvement in Australia’s finances compared to what Hockey would have otherwise have faced should make life a lot easier for him as an Abbott (or, who knows, a Hockey or Turnbull?) government looks to secure a second term.

The only fly in the ointment is, having fought unsuccessfully to support the government’s previous cuts to the baby bonus and having railed against the “age of entitlement”, Hockey will have something of a moment of truth over whether he backs the end of the baby bonus altogether.

The long-running criticism of Wayne Swan as Treasurer has been that he has produced a fantastic economy but been hopeless at telling Australians about it. This budget is an excellent example of Swan’s time in the job: it makes some good calls, gets the overall direction right and will continue to produce one of the world’s best economies, but it is hopeless at conveying a message that makes sense to voters, let alone a Labor message. For that, as much as for other reasons, Labor faces a bleak future.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.