Now that cycling is increasingly a “mainstream” mode of transport, there are calls for cyclists to conform to the road rules. That prompts the question why some cyclists don’t in the first place.

Australians tend to see cycling as something special — it’s racing, it’s exercise, it’s “cycle chic”, it’s advocacy, it’s identity — but it’s not usually hum-drum transport like it is in Amsterdam. For many of us it’s a passion.

Sarah Goodyear at The Atlantic argues it’s time to change. She says cycling is now a mainstream form of transport, and cyclists should therefore obey the road rules and be more respectful of pedestrians. Oliver Burkeman at The Guardian agrees. He reckons it’s time cyclists started stopping at red lights.

If they’re right, the pay-off from regularising cycling could include greater respect from motorists, improved safety, expanded facilities and a better relationship with pedestrians.

There are some important issues here. Is greater compliance achievable? Would it really deliver the claimed benefits? Would there be any (negative) unintended consequences? I want to take a step back and look at why some cyclists disobey the road rules in the first place.

Here’s an obvious one: the probability of detection is low. Provided a cyclist isn’t involved in an accident and isn’t riding in the CBD, getting caught for breaking the rules is no more likely than getting pinged for jaywalking. There aren’t many cops around, and to the extent they’re interested in cyclists, it’s pretty much limited to cycling-specific infractions like failing to wear a helmet.

Nor do cyclists have to worry about losing their licences. They might cop a fine, but that’s pretty much it. A cyclist’s biggest incentive isn’t to obey the rules but to protect life and limb and minimise effort.

“Cyclists see themselves as more like pedestrians than drivers … they ‘negotiate’ red lights.”

Another reason is the road rules were primarily designed to facilitate motorised transport, not human-powered transport. Some rules make less sense or are too inconvenient for travellers who rely on their legs. Cyclists see themselves as more like pedestrians than drivers. Like walkers, they can’t do much damage to other road users. They “negotiate” red lights at risk only to themselves, but very rarely “run” them.

The most important reason, though, is one that’s often overlooked. Cyclists who ride on roads aren’t representative of other road users — or of the broader population. They’re predominantly males and mostly younger ones at that. Moreover, they tend to be toward the risk-taking end of the spectrum. That’s not surprising — those who are more risk-averse are likely to perceive cycling in traffic as inherently dangerous and avoid it.

I expect it would be very hard to persuade risk-takers that there’s value in waiting at red lights when there’s nothing coming.

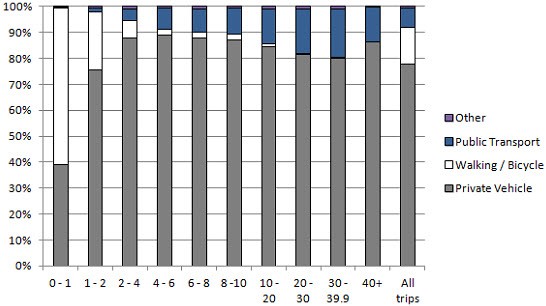

Mode share for Melbourne, by trip distance (horizontal axis, in kilometres) — data from Vista.

Of course there’s a sub-set of motorists who are risk-takers, too. The difference is they’re a minority of drivers. In the case of cyclists, however, risk-takers constitute a large proportion, perhaps even the majority, of those who currently ride on roads.

Motorists tend to assume cyclists who ignore the road rules or behave inconsiderately toward pedestrians are typical of all cyclists, whereas drivers are far more law-abiding. But that’s not comparing like with like.

It would be a mistake to think that the current cohort of cyclists is typical of the next wave waiting in the wings. These potential on-road cyclists are likely to be more risk-averse and probably therefore more inclined to “behave” if they can be induced to take to the streets.

Indeed, it’s never a good idea to assume the behaviour and values of existing users — when they’re very small in number — are representative of potential users.

Crikey encourages robust conversations on our website. However, we’re a small team, so sometimes we have to reluctantly turn comments off due to legal risk. Thanks for your understanding and in the meantime, have a read of our moderation guidelines.