[Soho Pam, outside the French House.]

Sitting at the Deco tables outside Bar Italia, scoping out the row of 18th-century brick terraces opposite, watching them load pallets of spirits into Ronnie Scott’s jazz bar, I was going through old notebooks and found “Pam hasn’t been seen for a while”.

“Soho Pam”, a stooped stout woman in owlish glasses, begged a living in the eight blocks of the south east corner of London’s “square mile of vice”, round the pubs that have become famous far beyond its environs: The Coach and Horses, the French Pub, the George. They’re all studded into Soho, a grid of 18th-century streets, blackened brick three-storey terraces, ground-level shops and bars, flats and offices above, suits and hookers in the streets, trannies and the crazies, every day, every hour, a little play, an exhibitionist’s dreamscape. Pam had arrived here sometime in the ’90s, from godknowswhere, and started working the punters, a pound here, 50 p there, for the seven quid a night she paid for a hostel bed in Pimlico. She was pasty and flabby, her stumpy teeth were eight shades of brown, but she had a beatific smile and a disarming childlike manner. “Love you”, “kiss kiss,” she trilled when you gave her a quid, hugging you round the midriff or demanding a smack on the lips. By the 2000s, she’d built up a bunch of “regulars”, who would cough up more or less daily. She got the seven quid early, and the rest went on Mars Bars and the bookies. People took her shopping, to the doctors, eventually got her a supported accommodation flat. She got lonely in it, went back to the hostel, kept working the streets and pubs, the old Jeffrey Bernard/Private Eye crowd at the Coach, the remnants of the Francis Bacon/Dylan Thomas/dying actors mob at the French pub, up through the tight terraced 18th-century streets, crowded with restaurants and bars, s-x shops and hairdressers, old tailors and new chocolatiers, past the Lorelei, an ancient joint with Formica tables, fake wood panelling, and a menu handwritten in the 1960s, to the new places — Milkbar, one of the dozen or so Brunswick Street-style cafes, usually Kiwi-run, that colonised London in the 2000s, through the gay strip along Old Compton Street, to Bar Italia, where the ambos drank coffee and gave her free medical advice, and back to the Coach again. She knew everyone, knew everything going on, passed the gossip from one end to the next, a shuttle flying through the loom, a McGuffin in the story.

“Soho has been dying a long time, dying since it was born, a spec-built property development carved out of the King’s hunting fields …”

When I left London in 2000, she was there working the street, and was there when I came back in ’06 and again in ’10, when, realising a long-held dream, I moved into the place, getting a “studio” hahaha flat above a tattoo parlour and a karaoke bar, became, among other things, a Pam “regular”, learnt to pretend not to see her when she came out of the newsagents with a fistful of scratchies 10 minutes after I’d dropped two quid on her. One day last year, she turned up yellow. “I’ve got a cyst on me liver,” she said. Then she was gone for a couple of weeks, then she was back healthier than ever. Then I went to the States for the election, came back four months later via Newfoundland and Peru and faced with another rent hike — garrets going at a premium these days — realised that it was no longer feasible to stay. Dug out a few notes for a valedictory piece, and looked at the Pam sentence, wondered if it was too cheesy. Realised I hadn’t seen her since I’d been back, and asked Sergio at Caffe Nero where she was. And she wasn’t absent. She was dead.

****

She’d died a week before Christmas, ferried to hospital one last time by a French pub regular. The cyst was cancer, and it always had been. She knew that, so did some others, most didn’t, and her death went through the place like a storm-front chill. Tears sprang when Sergio told me; then I told someone at Milkbar and they had the same reaction, and on it went. There was pity in it — though Pam, it was later said, had expressed no fear at her impending demise — but something else, too. Pam, never thinking much beyond the next hug or betting slip, had been a spirit of life, pure and undiluted, an existence unhedged by projects, projections, image, self-fashioning. In a place where you can walk into a cafe and hear, literally, half a dozen simultaneous conversations about screenplays, production dates, remixing the vocal tracks, getting funding from Channel Four and Film Estonia, where actors who have been “resting” since they did a three-line role in the Sweeney circa 1976, turn up to the French Pub at noon, every noon, in black Homburg, grey astrakhan and golden Hermes scarf, and stroll onto the Gay Hussar, the Groucho, Black’s and back to the French, amid all those desperate attempts to make meaning out of a brief time on earth, Pam was a memento vivi, existing in a pure present the rest of us could only access and maintain by the regular application of ethyl alcohol. Self-pity was a part of it, and an awareness also that Soho, this Soho, was dying with its inhabitants. Pam went. The old tobacconists in Greek Street went a week later, became a gelato bar, another s-x shop closed, its ratty peep show booths and day-glo fluorescents thrown into a skip — all the old trades going.

But Soho has been dying a long time, dying since it was born, a spec-built property development carved out of the King’s hunting fields — so-ho! Is a hunting cry — in the 1600s, the first expansion of London westward after the Great Fire. Around Soho Square in the north-east corner, grand mansions were built, home to an aristocracy moving to town from country piles. What hopes the founders had of an upmarket venue were soon dashed however, when an early occupant, the Duke of Monmouth, staged a failed coup against James II, was arrested and executed in 1685. The aristocracy moved south, to a larger square laid out by the Earl of Leicester. By then, the place had already attracted its first “alternative” population — Greek refugees from the Ottoman empire, followed by French Huguenots, and then all comers. The large plots were subdivided and spec builders — Frith, Meard — put up the narrow plain brick terraces that persist today. By the 1750s, the place was bohemian, artistic, criminal, scurrilous. Piccadilly Circus, Regent Street, Shaftesbury Avenue — the places that now symbolise London did not yet exist, had not yet been built when Soho was already a century old, had died and been reborn twice. Canaletto came and painted it, Leopold Mozart bought his family and prodigy son Wolfgang to stay for a year, and give afternoon concerts in Frith Street. There’s a blue plaque there now, one of three in the street. You could put one on each house. Joseph Banks lived at the north corner. Humphrey Davy invented the diving helmet in a street just off. Logie Baird invented TV four doors down. My place, no.18, was the home of Samuel Romilly, the jurist often known as the founder of modern English liberalism, who reformed the entire groaning, mediaeval English law, and began a campaign against the death penalty. The place has been remodelled since, except not so much — the crooked beam that runs across the main internal wall, dropping about 30cm along six metres length, the one I saw every morning for three years, is the one he saw every morning. Each street, each house resonates with the same ghostly sense. Samuel Johnson, Blake, Shelley, Hazlitt, Chesterfield, Marx, Verlaine, Dylan Thomas, Orwell, Bacon, all the way up to the S-x Pistols and beyond, Soho is the original inner-city bohemia, the one from which all others have been budded, dying and renewing itself every half-century or so, its rebirth attended by a funereal lament for what has passed away forever.By the 19th century, sequestered from Mayfair by the new streets — Regent, Shaftesbury, Charing Cross — driven through, it became a small Europe-in-exile, the ethnicity changing every block, Italians in Brewer, Germans in Dean, Jews at the northern end, the French around Old Compton. By the 20th century, the warren of cheap rooms, and the continental-style cafes drew a new type, the writer who never spilt ink, the artist who never picked up a brush, the intellectual whose ideas were aired exclusively across a bar. With them came those in search of morphine from obliging quacks, starving actresses and artists’ models who had turned to a new, i.e. old, profession and razor gangs that ran the streets, ensuring that some people didn’t step four blocks away from their neighbourhood for decades at a time. By the 1930s, people were talking about “sohoitis” — the fatal disease whereby those who actually moved to the square mile on the strength of early artistic success never turned out another book or painting again, dying in the gutter with a liver as pink and sweet as the pate in the delicatessens lining Old Compton. Dylan Thomas, Francis Bacon, Orwell and others all made a point of living outside and commuting in. At the other end, are the people you meet at the French who will, if you buy the drinks, talk about Manray, the history of aniseed, Yeats’s A Vision, Motocross, the Nagaland question, metopes, billiards strategy, choreography notation, U Thant, Deal or No Deal, anal sex and God, the talk coiling upwards into the night, uncollected, never to be collected, most probably not worth being so, but seeming, as you break another 20 for a double Laphroaig as if it is a tragedy that it is slipping away, a sort of nohemia. And then between, there’s a sort of middle zone, a subhemia, people who would otherwise disappear, finding the wherewithal for one great work that captures life in its immediacy in a way that no more measured piece can. The current obsession — the place breeds serial obsessions — is the George Barker crowd, a trapezoid of folks from the ’40s and ’50s, focused on the mad, bad, sometimes great, now mostly forgotten “apocalyptic” poet:

Fiend behind the fiend behind the fiend behind the

Friend. Mastodon with mastery, monster with an ache

At the tooth of the ego, the dead drunk judge:

Wheresoever Thou art our agony will find Thee

Enthroned on the darkest altar of our heartbreak

Perfect. Beast, brute, bastard. O dog my God!— from Sacred Elegy V (V!)

Canonised by Yeats and Eliot as the next great poet, Barker accumulated 14 children from four wives, one of whom was Elizabeth Smart, a Canadian heiress who fell in love with him from his poetry, tracked him down and broke up his marriage, was in turn used, abused and betrayed and out of it wrote By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept, and you’ve heard of that, because it is the one perdurable work of art among the whole set, a prose poem hymn to obsessive, masochistic life-destroying love. A minor hit when it came out in 1945, was re-released by Virago in the ’80s as a “cautionary tale” against feminine masochism, which is … there are no words. It’s like putting Plath on the high-school syllabus so teenage girls don’t get any funny ideas. Grand Central Station makes you believe that there is nothing else, no possible other way to live, than at this extreme, consumed in the reaction. That Barker’s style lives on in Smart’s charged prose, that Smart by the evidence of all her other work could not otherwise have produced a masterpiece is only irony if you ignore the tragedy.

They drank round here. Barker drank round here the evening Smart nearly bled to death giving birth to his child. Lower down, with them, there were people like Philip O’Connor, a chancer who wrote well but married better. Author of the very strange Memoirs of a Public Baby, O’Connor married seven times, rich young women mostly, whom he fleeced and then left. One of them Jean Hore, was the unrequited love of a man even lower down the pole, Paul Potts, a Canadian non-poet, who used to hawk his terrible verse round the pubs in self-published broadsheet versions. O’Connor married Hore, bankrupted her and then put her in an asylum, where she died, hopelessly deranged, 50 years later, in 1997. And we know of all this becuase Potts, out of the experience, out of grief and rejection, wrote the incomparably strange Dante Called You Beatrice, ostensibly a short testament to unrequited love, really a harrowing account of life failure. Potts came to Soho in the ’30s, was in the Commandos, and then fought for Israel in the 1948 war. He drank with Orwell at the Dog and Duck, a pub I can see from my window, and wrote the best single memoir of him, Don Quixote On a Bicycle, the only piece from which Orwell emerges as a real human being. In the final passage of the book, he remembers the moments of life:

‘Looking backwards from beyond half time…

The thrill of crossing the Italian frontier on one’s way to Tuscany…talking the night away with George Orwell before a highland fire, smelling the peat burning and the taste of Gaelic wine….standing at the bow of an immigrant ship as she sailed under Mount Carmel into Haifa Bay…seeing a German soldier having to salute the Jewish flag…remembering one girl coming towards me through the corridor of a city jail with a pound of strawberries, a copy of Leaves of Grass, and a kiss…’

‘Stated like this it sounds an exciting life. But these were just oases dotted across a desert of loneliness, a quarter of a century wide….’

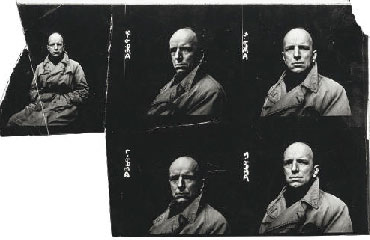

Reading between the lines, Potts had, of course, a better time of it than he wished to say. He had the sort of time you have in Trisha’s, the last dive bar here, round the corner, where you can meet in short order jazz hopefuls, tourists from the north, minor gangsters, Pete Doherty, Porno Paul Ocalan’s English translator, black Christian DJs, someone who knew Leigh Bowery or says they did — the sort of night where you stagger out, throw up blood into the gutter and curse the last eight hours you had. That was Potts’ life, he left some record of it, and beneath him, the people who admired him, we will never know of. They’re ghosts in the air, afternoon smoke. Here’s Potts in his prime:

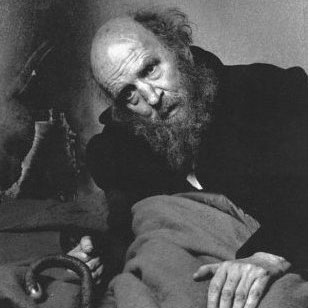

And here he is, in the ’80s, photographed by Christopher Barker, one of George’s sons:

That’s how subhemia ends. Such is life.

The war made this last Soho, a place to congregate in the blackout, much of it around the York Minster pub, run by a French family, and chosen by de Gaulle as the unofficial Free French headquarters, thus guaranteed a continuous supply of drinkable wine. World War I had killed “Little Germany”; World War II saw the place’s Italian population interned, rounded up in an afternoon, fascist and anti-fascist alike (“collar the lot,”Churchill had ordered), their shops and flats left derelict, unmanaged and squatted, oft as not by pimps. By the early 1950s, it was said there was a prostitute every three yards, lining the streets, using the alleys to ply their trade. The London County Council proposed a Ceausescuesque plan to demolish the whole area, replacing it with evenly spaced office and tower blocks; luckily, the city was too poor to implement it. By the time the prostitutes were driven inside by a 1959 legal reform, porn had arrived. It dominated the western half of the area, to Piccadilly, for four decades, spreading out from the Parisian-style Raymond revuebar to dozens of clip joints, smut racks and basements smelling of lube and sparkling wine at £100 a bottle. East Soho was less infested, a place where the pubs — which closed in the afternoons — were interspersed with drinking clubs for those desperate hours between two and six, the Colony, Gerry’s, the Troy, and places lacking even a name, just a door and a name (“Barry/Trevor/Lionel sent me”). They survived as illegal speakeasies right into the ’90s, when pubs gained the right to open after 11, and a whole deliciously illicit world was wrecked with the stroke of a pen (curse of Romilly). The best place after Trisha’s, the best zero degree bar, was the Spanish, a basement consisting of a tiled room, the bar a three-metre long commercial supermarket fridge full of slabs of “wife-beater” (Stella Artois), atopped by an open slab, a two-litre bottle of vodka with an optic, and a stack of clear plastic cups. The sound system appeared to have been purchased at Cash Converters. By midnight, every night, it was jammed shoulder-to-shoulder.

By the time it went, the sleaze was going as well, victim of a New Labour clean-up, which addressed the issue of exploitation and trafficking of women by scattering it out of view — although there are still about 30 open doorways advertising, on coloured cardboard, written in texta, “model upstairs”, lettered like a grade 6 project, a heart dotting the “i” often as not. The Sohoites died, Bacon, Bernard, Peter Cook, Muriel Belcher, the Colony closed, the old Italian tailors moved to granddad flats in Essex, and the meeja moved in, the TV companies that are nothing but a shingle, a shared office space and a pitch to UK Gold, the ad companies, the distributors, the post-prod houses, and on and on. They’ve been there since Logie Baird projected the deeply unsettling image of a doll’s head across a room (there’s a re-creation of it here); now they’ve come to dominate the place. They like espresso in bento-box cafes, and Thai tapas and bars, so the old Italian restaurants have died one by one, leaving only their tiny mosaic-tiled patios embossed with their names — La Bella Isola, Il Siciliano, Biagi’s — out the front. And last month Lorelei went, after 45 years, its owner having made more money in the past five renting it out as a film set for countless bad period-piece movies than by slinging burnt lasagna. That’s a loss. Radio Girl proposed to me there and then an indecent amount of time later, citing a desire to “be bohemian”, left me — me, an actual writer in an actual garret, with actual Sohoitis — for an accountant who blogs reviews of eBook readers, suggesting a basic confusion about the bohemian thang. But ah, she was here, this is her story, too. Pam gone, then the Lorelei, and even the Coach and Horses is under threat, a pub left unrenovated so long that all the beers whose names are branded into the woodwork over its top shelf — Bass, Double Diamond — have long since ceased to exist.

“… I left Soho, a flat put into a storage bin, and with two duffel bags of notebooks and necessary junk in the back of a black cab.”

The Coach would be the final cut; for the rest, I’m more equivocal, which surprises me in myself, a young fogey since the age of 15, in perpetual mourning for the passing of things I never experienced or had an emotional connection to. But the Soho being mourned existed for no more than one-eighth of its half-millennium existence; whatever incursions the chains make — a Starbucks here, a Tesco there — its distinctive and individual spirit survives in ceaseless transformation. Increasingly it is becoming a place for the well-heeled, although a third of its residents remain public-housing tenants. Should Westminster start to eject them, it really will go. Thankfully, the Cameron/Osborne government has rushed to its aid by plunging the country into a fresh recession and renewed decay, that ever-reliable source of creativity. Ten new shops and restaurants opened last year, along the three of four blocks I walk, and do not leave for weeks on end; six have now closed down, three have not been replaced by anything except newspapered windows and a landlord’s repossession notice. More of that, please, but even if there is no more, the place persists. Walk the streets, the squares, and you feel the people who lived and loved here across the centuries like they were neighbours, still there, endlessly projected, like Logie Baird’s eerie mechanical television broadcasts, Huguenots in the corner shop, poets in the Starbucks. Of all the things I thought I’d find in Soho when I moved here, nothing surprised me more than what subsequently made it impossible to quit — that beneath the crowds who swarmed in every night to the theatres and clubs, the babylonian leather-drag-bear bacchanal up Old Compton each evening, there remained, of all things, a village that reappeared each morning. In Bar Italia, the same old tailors turn up at seven each morning to play the antique fruit machine, Lorraine brings the papers, the ambos round out their shift with hot chocolate, the stalls set up in Berwick Street market, the neat young men come out of upstairs flats to walk their bonsai dogs, Kiwis in promising new bands log on for their Flat White shifts, and Dante and his Bettie Page-alike wife open the tattoo parlour, the day shifting into late morning, the French opening for the cravat crowd, and the Caffe Nero flips over into a Grindr hotspot. A day is a century. The signs and the things in the windows change, the place lives on. Waterloo was yesterday, the Glorious Revolution a week ago. Out my kitchen window, there’s a wall that, when the First Fleet set out, was covered with the black soot that still adorns it. Three winters, 200 winters, the snow has turned the black white and then it has gone black again.

****

Pam’s funeral was at a crematorium in Finchley, her family having moved it into London, from Sussex, when they found out, belatedly, that their rarely seen sibling was some sort of famous. By the time she died, Pam had been written up, photographed, a dozen or so times, threading through history now, disappearing from one page to the next. I did a small one for The Guardian, earning for my pains, a vague threat of harm if I made any money out of it by one of Sid Vicious’s old girlfriends. Prepping for it, after the service, her brother and sister flipped through a photo album, the old style, puffy cover and plastic pouches. In Kodachrome golden glow there was a brown-haired girl, in school uniform, in marching band costume, in the denim and décor of the ’70s, growing and then not growing. Pam’s sibs remembered a cheerful, clumsy girl who finished school, held down jobs, started a computer course, and then began to fade. They moved out of home, Pam stayed on. There was a diagnosis of “mild schizophrenia”, simply a catch-all term for a set of odd symptoms and conditions. Then the photos, late 20s, ran out. Pam’s parents had died, and she lost all bearings, wandering away from family and home, and landing after god knows what in Soho, fed, clothed, coiffed regularly by Kate Moss’ hairdresser, and finally housed in a flat she liked, fixed up by a couple of Coach regulars. But the mystery was no mystery. Indeed there was less to it even than that, for a fortnight later I realised, with a shock like a car-smash, that Pam had almost certainly suffered from Williams’ syndrome, a genetic condition that matched her exactly, causing short stature, elfin face, spaced teeth, an inability to lie, perfect pitch, a lack of inhibition with strangers. I checked with a doctor; he said it sounded highly likely. I wondered whether I felt differently about Pam’s guilelessness, her holy innocence, now that it seemed to have been written down in chromosome. I decided that I didn’t, or maybe, simply, that I wouldn’t. However she had come to Soho, and who, whatever she had been, she had entered its world, a place, for all its pretension and self-regard, that did not kick her to the kerb as would have happened elsewhere. She loved, and was loved, and flowed into the history of a place that had become over the centuries somewhere where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in. Such places, the new arrivals each day, make life out of loss, make it at least possible that there is no tragedy that cannot go unrecuperated.

Two weeks after Pam’s ashes were scattered to the winter sky, I gave up the flat in Frith Street, got a few months’ reprieve with a minuscule place , a cupboard with a kitchen really. And then last week it was all over, and I left Soho, a flat put into a storage bin, and with two duffel bags of notebooks and necessary junk in the back of a black cab. Dean, Berwick, Old Compton streets were gearing up for the late afternoon as they always would. It felt like leaving a city of birth under siege, with nothing but a spare shirt and gold fillings, like exile from the place where exiles go.

So, so lovely Guy.

Thank you for this.

That was really quite beautiful… and certainly makes up for yesterday’s list story. Sorry to hear of Radio Girl’s departure too.

A marvellous piece. If you have time, let me know where you have gone.

Rai Gaita

Rings deeply felt. Well worth the journey. Quite the best testament to the evocative power of words. Wouldn’t work so well in film.

my Crikey subscription is due to expire today, I’ll be renewing it on the strength of this article alone.