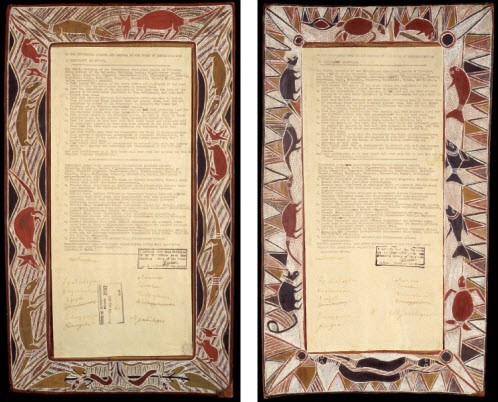

In a small display case in a dimly lit room in Australia’s Parliament House in Canberra — cheek by jowl with a facsimile of the Magna Carta and Australia’s constitution — sit three panels of richly painted stringy bark. These are the 1963 Yirrkala bark petitions.

The first two of these petitions were presented to the Commonwealth Parliament in August 1963 and represent the first documents received by that parliament that recognised the existence, but not the primacy, of Aboriginal law and claims to ownership of their ancestral lands.

The petitions were unsuccessful — the first was the subject of an extraordinary technical challenge by then-territories minister Paul Hasluck — but that did not deter the Yolngu traditional owners, who in December 1968 issued writs in the Supreme Court of the Northern Territory against the Nabalco Corporation, which had secured a bauxite mining lease from the federal government. In that claim the Yolngu claimed unextinguished communal native title to their lands.

In 1971 Justice Richard Blackburn dismissed the Yolngu claim but importantly did acknowledge for the first time in an Australian higher court the existence of a system of Aboriginal law. In his judgement, Blackburn used the following words, which have rung down through the years:

“If ever there was government by law rather than government by man then this is it.”

By 1971 the rest of the country had taken note of the Yolngu persistence for justice and their clamour for constitutional change, which had already resulted in the amendment of the Australian constitution in 1967 to give the federal government a clear mandate to implement policies to benefit Aboriginal people.

In 1976 the Commonwealth recognised Aboriginal land rights over some land the Northern Territory. Terra nullius, the odious philosophical basis of the non-Aboriginal invasion and occupation of Australia, was finally dispatched to the dustbin of history by the High Court in Mabo’s Case in 1992.

But in 1963 Yirrkala and north-east Arnhem Land were in turmoil. It is important to remember — and how quickly we forget — that in 1963 the Aboriginal people of Arnhem land were subject to the provisions of the Welfare Ordinance 1953, which under Hasluck’s authorship enshrined the assimilationist and paternalistic approach that had characterised much of government approaches to Aboriginal issues for many decades For more background on these matters see the time line and references here.

And the typewriter?

Wandjuk Marika, the son of revered Yolngu elder Mawalan, as reported by Edgar Wells in his Reward and Punishment in Arnhem Land 1962-1963, had access to an old typewriter, which he used for formal communications to Mission staff and the Australian government.

In August 1963, after the prompt from parliamentarian Kim Beazley snr following a visit to Yirrkala in May 1963 that the Yolngu should “make a bark petition”, two petitions on bark were sent to Canberra, again with text typed in Wandjuk’s old typewriter.

As Wells notes at page 81 of Reward and Punishment in Arnhem Land the effect of the Petitions on arrival in Canberra was immediate and dramatic:

“The petition carried with it the flame of its own success and notice was served on the Commonwealth Government and on interested political leaders that there was a serious discontent amongst the Aborigines of Australia’s Arnhem Land area concerning a lack of communication with them over the transfer of land within an Aboriginal Reserve to mining interests whose representatives had not consulted with the local Aborigines and offered no compensation for loss of land traditionally considered to be under Aboriginal control.”

Thanks for the article. The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies is proud to present an online exhibition of the Yirrkala Bark Petitions 1963 to coincide with NAIDOC Week.

The online site provides the images of the petitions, as well as historical information and research links. The online exhibition is at http://www.aiatsis.gov.au or here

http://www.aiatsis.gov.au/collections/exhibitions/yirrkala/home.html