Sydney Morning Herald political editor Peter Hartcher has fired back at claims made by former Fairfax colleague Kerry-Anne Walsh in her book that he backed Kevin Rudd during Gillard’s prime ministership. And he’s not the only journalist fingered in a thorough examination of how the press gallery works.

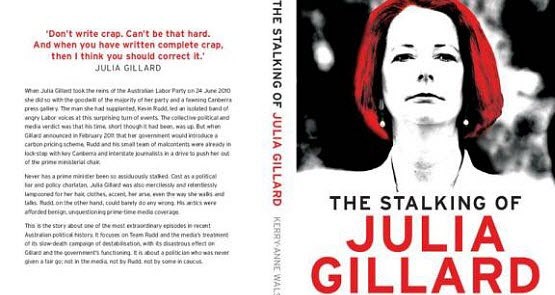

The Stalking of Julia Gillard — subtitled “How the media and Team Rudd brought down the Prime Minister” — is already into its third print run after two weeks on the shelves. The 25-year press gallery veteran, who was most recently The Sun-Herald‘s political editor, doesn’t hold back from naming and shaming journalists she believes became players in a destabilisation campaign against Gillard.

Hartcher — described by Walsh as “Rudd’s absolute favourite person in the press gallery”, “Rudd’s main media mouthpiece”, “Rudd’s mate” and “a tosser” — receives the harshest treatment. When asked why Hartcher features so prominently in the book, Walsh told Crikey: “Because his writings were so emphatically pro-Rudd.” She adds she’s not the only person in Canberra, or the general public, who thinks so.

Among the many Hartcher stories Walsh references is a February 2012 piece in which he observed: “As he returns, in all likelihood, to the prime ministership in the weeks ahead …” A week later, Gillard defeated Rudd 71 votes to 31 in a leadership ballot.

But Hartcher told Crikey: “I have no history as a Rudd supporter and am not a Rudd supporter. With Rudd, all I was doing was pointing out the political reality, based on established polling, that he was the preferred candidate to lead the Labor Party. If pointing out political reality now qualifies as cheerleading, then I guess I am guilty.”

Hartcher has not read Walsh’s book but says her thesis about the media’s role in Gillard’s demise sounds like a “conspiracy theory”. “This is all a bit fringe and bizarre and confected,” he said. “I’m not upset, I’m not shocked, I’m not angry, but I am bewildered.”

On Saturday former Labor leader Mark Latham described Hartcher as “the equivalent of Rudd’s press secretary, a political agent masquerading as an independent reporter”.

But Hartcher says people have short memories. “When Rudd was PM I was one of his harshest critics,” he said. “In Barrie Cassidy’s book The Party Thieves he wrote that my commentary on Rudd’s decision to abandon the emissions trading scheme would have led marginal seat members to think of supporting Gillard … I have no private or personal or political attachment or indebtedness to Rudd whatsoever. It was the story I wrote [that Rudd’s chief of staff was testing his caucus support] that provided Gillard the trigger to challenge Rudd.”

Hartcher added: “At no point did Julia Gillard herself, or any of her staffers, tell me I was a barracker for Rudd.” And he notes his story about frontbenchers Bob Carr and Mark Butler shifting away from Gillard was borne out by their votes for Rudd in the June leadership ballot.

“It’s an unhealthy relationship, and it’s not serving the public interest where everything is off the record and no one has to put their names to anything.”

Walsh’s book was initially going to cover the workings of Australia’s first minority parliament in 60 years. But she decided to shift focus because the parliament’s policy achievements were being overshadowed by constant leadership speculation. During the Gillard years, she writes: “Every rule in the handbook of good journalism was broken.”

Walsh’s core contention is that the use of polling results and quotes from anonymous sources is out of control in the Canberra press gallery. She argues off-the-record briefings from Rudd and his supporters led journalists to repeatedly overestimate his level of caucus support and to underplay the minority government’s policy achievements. This would have been less likely only five years ago, she says, when pressure to file around the clock was less intense and editors vetted stories more closely.

“I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything like it in terms of the daily rolling out of anonymously sourced stories. Maybe [journalists] just need to say, ‘put your name to it or I won’t bloody run it’. Politicians can whistle up any story they want with anonymous briefings. It’s an unhealthy relationship, and it’s not serving the public interest where everything is off the record and no one has to put their names to anything,” she said.

Walsh says journalists should have publicly questioned Rudd about whether he was briefing against Gillard and called him out for undermining the PM.

On this point Hartcher said: “I have accepted confidences from many prime ministers, including from Julia Gillard before and when she was prime minister. When you agree to a confidence you have a professional obligation to maintain it — that is why people are prepared to talk to us and to leak things to us. I’ve had briefings from Keating, Howard, Gillard, Rudd — about every significant politician from any party we have — in order to inform the public, not to benefit any one of them.”

The media’s fixation on Gillard’s gender is another theme of Walsh’s book, though not a dominant one. Walsh pings the Herald-Sun for claiming Gillard looked like she had “won a date with George Clooney” when she met Barack Obama. And she savages Hartcher for his analysis of Gillard’s misogyny speech (he concluded the PM “showed she was prepared to defend even the denigration of women if it would help her keep power”). “I have copped a lot of flak on that, but I think I will be vindicated on this,” Hartcher said. “Her deliberate use of gender for political exploitation only became clearer as the months unfolded.”

While Hartcher receives the most stinging criticism, Walsh also gives press gallery reporters Phil Coorey, Dennis Shanahan, Simon Benson, Gemma Jones, James Massola and Michelle Grattan a serve in the book. Lenore Taylor, now of The Guardian, is praised for her use of “facts and even-handed quotes”, and the ABC’s Barrie Cassidy emerges as a hero for calling out Rudd’s briefing tactics. News Limited’s David Penberthy is also applauded for his columns.

“KA”, as she’s almost universally known, experienced Rudd’s less-than-charming side in 2007 when he tried to kill a story casting doubt on his tale of childhood eviction. In Stalking she also recalls Rudd casually mentioning to her during a 2006 interview that then-Labor leader Kim Beazley might not be in good health. “It was a sinister, subtle undermining,” Walsh concluded, “that put me on high alert that Rudd was a sniper in diplomat’s garb.”

So Hartcher has not read the book ….. but ….. he has an opinion

says her thesis about the media’s role in Gillard’s demise sounds like a “conspiracy theory”. “This is all a bit fringe and bizarre and confected,”

…and is not afraid to use it.

Senior journalists on the drip? No surprises there.

Personally I think alleged corruption amongst some union bosses and politicians, and the ex PM’s strong identification with some or all of those unions, was another significant factor. Health unions in Vic and NSW, ICAC in NSW.

Was this the vibe playing into PM G’s involuntary nasal drone? The sub dialect known as English-unionist?

Overall I’m not really sure journalists are that significant – though I do grate my teeth at the implicit white supremacism in anti boat people (read anti brown people?) in GJ’s writings.

Was the ugly News Ltd treatment all a get square for winning based on Work Choices in 2007? I wonder.

And what about Paul Sheehan’s bias in Fairfax (the proverbial Palid Man).

Hartcher cites Barrie Cassidy as authoritative on his work. He might wish to re-read Barrie’s column in the ABC Drum on 3 Dec 2012, which points out the bias in Hartcher’s coverage of ALP leadership during the year.

Once upon a time the Canberra press gallery addressed MP’s as Senator or Mister. To be given a background briefing – mostly about policy matters – was uncommon. Today MP’s have very young and inexperienced media advisers who are, at the best, inept and make fools of their masters. There was a time when MP’s didn’t ostentatiously pose for pix – photographers had to be good enough to catch the moment. And reporters good enough to catch the stories. Now, as Tony Abbott once did publicly, MP’s offer to “do it again for the cameras”.

There’s now a total over-reliance on a reporter ‘capturing’ an MP to be his/her “contact”, while MP’s (try to) capture a reporter. Who wins? Not journalism. I was also saddened to see Peter Hartcher’s stories veering more and more to the 1KRudd camp as the phoney war went on. I too turned to Lenore Nicklin for actual news. We need desperately for media bosses (editors etc ,not owners) to review the way we operate in the gallery, including the continuing mixing of comment and ‘analysis’ with news. Hartcher deserves a carpeting. However, he will hopefully analyse his errors of judgement. But now it’s a game between the gallery and the MP’s – who can capture who first and who can be the winner.

I just don’t understand how Peter Hartcher could tolerate having to spend so much time with psycho Kevin. And I would like to know if Peter ever gave advice to 1KR.

“Don’t play with the media if you have a conscience”?