Stephanie Guest started Haplax in 2011 at Melbourne University with her fellow student Anna Heyward as a response to the lack of OzLit being taught (see PDF of Haplax origins). Check out the remarkable list of people they talked to or hosted last year.

Haplax 2013 started late — last night at Readings in Carlton; Stephanie has blown the joint and our ringmistress was the serene Anna. The guest was Les Murray, fresh from doing the Patron thing at the Mildura Writers’ Festival. A cold night but we were rubbing shoulders and Les — it seems about right to use the familiar “Les,” though he is Mr Murray to me — launched straight into a reading from his Best 100 Poems of Les Murray (currently out of print; isn’t it remarkable that a poet could have a book of 100 best poems?!).

Haplax 2013 started late — last night at Readings in Carlton; Stephanie has blown the joint and our ringmistress was the serene Anna. The guest was Les Murray, fresh from doing the Patron thing at the Mildura Writers’ Festival. A cold night but we were rubbing shoulders and Les — it seems about right to use the familiar “Les,” though he is Mr Murray to me — launched straight into a reading from his Best 100 Poems of Les Murray (currently out of print; isn’t it remarkable that a poet could have a book of 100 best poems?!).

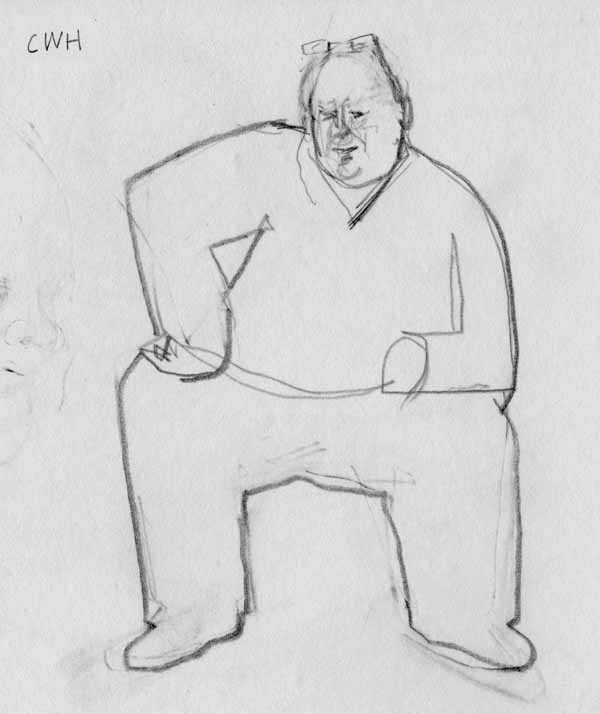

There was a ski poem; one about cows; The Mirrorball; The Blame (?); the moon man; Visitor (entire: He knocks at the door / and listens to his heart approaching); Oasis City (about Mildura); one about his autistic son Alexander. The poet was comfortably dressed in large shapeless sweater and trousers, draped over his enormous frame. He was once asked, What was his favourite brand of suit? Murray: The track suit.

He also read Eating from the Dictionary (about chooks, Hungarian for fowl) and The Glory and Decline of Bread, the latter being a nostalgic elegy of a food he loves (“Bread has become unfashionable”), which is a poem in his theme of the left-behind, the unacknowledged and underestimated — the underclass, exemplified in his most notorious title, Subhuman Redneck Poems. You know he identifies; but then bread is not a wholly humble metaphor.

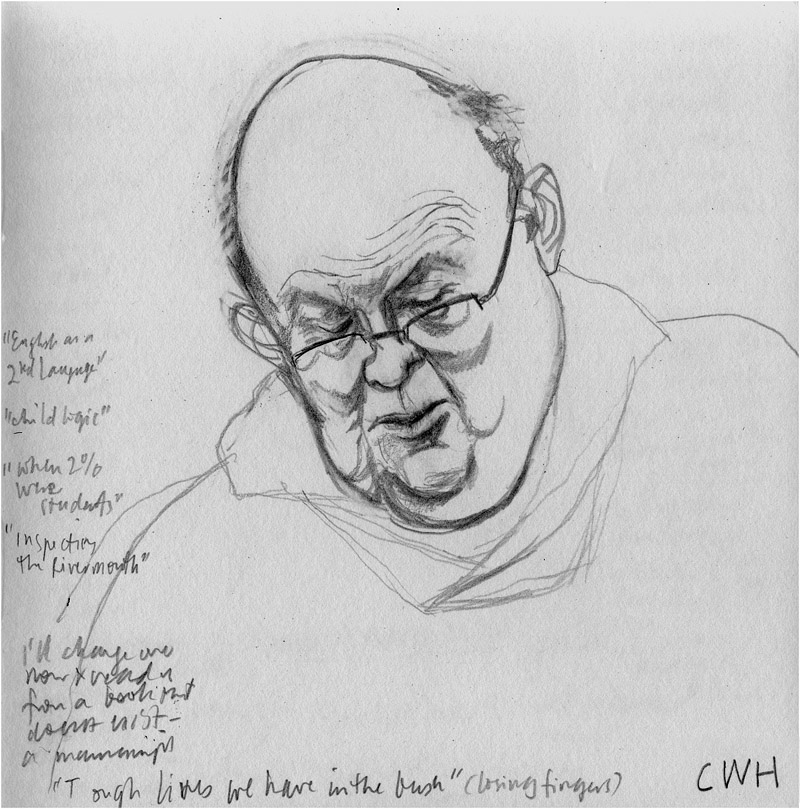

Then Les announced that he was going to change over and read from a book that doesn’t exist — the manuscript from his next volume. Murray is known for his evocative titles. He read the following:

Inspecting the River Mouth, about seeing (that other great river) Murray enter the sea; When 2% Were Students (about university in his day); Child Logic; and English as a Second Language. After which he declared, laughing: You got four world premieres tonight!

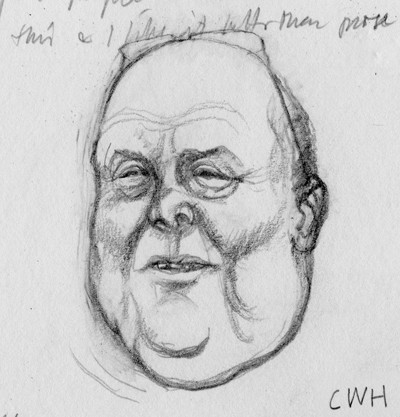

Unfortunately I could only keep drawing or attempt to transcribe, so I stuck to image making. Murray has a distinctive reading style, breathless and wheezy, rat-a-tat with emphases on rhymes if any and often finishing on a fade. His laugh is equally Murrayesque — a grunt-chortle as a punctuation, or a explosive laugh pitched at the ceiling.

Anna Heyward, maintaining superb sangfroid, inquired if Les was still writing on his typewriter rather than a word processor. Les replied that You want a messy page with corrections — so you can make it better. A clean computer page sets up a distance — and, he said, Why would I want to write a poem on a machine that sent a man to the moon?

Murray seemed to suggest that maybe Assange (and Snowden) might have a point — your keyboard, he said, more people might be able to hear you than you think. On English being the Latin of our day, and the great pidgin language, he remarked: English is great because of thieving.

A Murray aphorism: Never outlive yourself.

The evening ended with audience questions, and as I sympathised, we were mostly too much in awe to open our mouths and betray our shallowness so apart from a question about how he started writing poems — which answer Murray has given regularly, I guess, and one about Shakespeare — Murray indicated he wasn’t greatly influenced but looks forward to a closer reading of “the Scottish play” — he finished with a requested reading of Driving Through Sawmill Towns.

+ + +

Years ago I asked a friend, a great reader, her opinion of Les Murray’s poems. She said she found them very impressive but that they didn’t move her. I kinda knew what she meant, and I knew her comparson was Philip Larkin, whose wit is ballasted with a profound gloom grey-lit by an English looking back. Famously in This Be The Verse, and also in Sad Steps (my vandalistic compression of the first two lines and nearly last lines):

Groping back to bed after a piss

I part thick curtains, and am startled by

… a reminder of the strength and pain

Of being young; that it can’t come again,…

But here is the first stanza of Larkin’s Annus Mirabilis:

Sexual intercourse began

In nineteen sixty-three

(which was rather late for me) –

Between the end of the “Chatterley” ban

And the Beatles’ first LP.

And teh first three lines of Murray’s Rock Music:

Sex is a Nazi. The students all knew

this at your school. To it, everyone’s subhuman

for parts of their lives. Some are all their lives.

Both poets are singing about sex, but one is playing pop, and the other heavy metal: Larkin’s poem blithely ironic, Murray’s poem grittedly aggrieved. But if being moved is also to be enchanted and delighted, surprised and elevated, and dazzled, then here is Murray at suprahuman pitch, Bat’s Ultrasound:

ah, eyrie-ire; aero hour, eh?

O’er our ur-area (our era aye

ere your raw row) we air our array,

err, yaw, row wry — aura our orrery,

our eerie ü our ray, our arrow.

A rare ear, our aery Yahweh.

A rare ear our earthbound but monumental poet, his hearing at Kosciuszko altitudes. And he is Australia’s poet, or certainly one who knows the names or gives them. As fellow poet John Kinsella writes:

Murray’s influence on a generation of Australian poets has been incalculable. Few fail to recognise his linguistic brilliance, his intricate metaphysics, his ability to craft a poem and create a sense of place. Murray knows the value of naming — and he has named the points within his and his people’s territory. (Emphasis added.)

But while Murray’s poetry has a wide embrace I’m not sure that all of us are his people — this was Kinsella’s point, as he was kind enough to note — and I certainly felt that way listening to Les. This is a not unreasonable limit I think, even for a man who likes to dedicate his books To the glory of God (or, To the need of God).

And more:

The Paris Review interview

Read, search Les Murray’s poems at the Australian Poetry Library

David Naseby’s portrait of Les Murray in the National Portrait Gallery

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.